The History Of Silver Taps

One of Texas A&M’s most meaningful traditions, Silver Taps is more than a century old – and the hauntingly beautiful ceremony has evolved slowly over time.

Such changes had never been compiled into a full, written history until The Association of Former Students’ “History of Silver Taps” in the January-February 2022 issue of Texas Aggie magazine.

Now, The Association presents this research digitally for all to share, to grow in understanding and appreciation of this unique honor given by A&M students to those who have passed.

The Modern Silver Taps Ceremony

Silver Taps nowadays is held at 10:30 p.m. no more than once a month for enrolled students who have recently passed away. It is attended in silence by hundreds of students gathered in the Academic Plaza, where lights have been darkened.

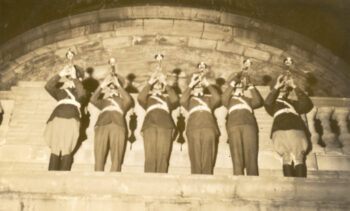

The Ross Volunteer honor guard marches slowly to the plaza’s center and fires three rifle volleys. Then, six buglers standing high above, out of sight at the base of the Academic Building’s dome, play a slow arrangement of “Taps” three times. The students disperse in silence.

The ceremony has been very similar for nearly 100 years. But it wasn’t always so.

1910s: Funeral Processions To Train Station

With a student body of fewer than 900 in the early 1910s, the death of a cadet would halt operations on the Texas A&M campus, according to news reports from that time. A&M would cancel classes, lower the flag and hold a funeral service. Cadets would carry the remains to the A&M train station, in a procession sometimes led by the band. The student’s roommate or other cadets might board the train with family for their friend’s final journey home.

The term “silver taps” begins to appear in the World War I era, when newspaper accounts mention it as part of military funerals and war memorial events at Texas A&M and elsewhere.

But it’s not entirely clear what is meant by “silver taps” in these cases. It could mean a rendition of “Taps” by more than one bugler, or simply highlight the use of “Taps” as a memorial.

One of the earliest references comes from Texas A&M’s The Battalion student newspaper on Feb. 6, 1918, with a cadet’s death from pneumonia: “Silver taps was sounded by the college band Monday night,” soon after he passed away at 6:35 p.m.

Following this, in the 1920s and early 1930s, references become more common to “silver taps” being played at Texas A&M on the night of a student’s death.

1920s: Trumpets Play Three Parts

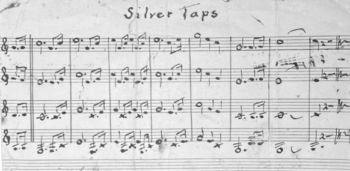

The music we know today as “Silver Taps” is a slow, three-part arrangement that has been dated to 1929, created by A&M band director Col. Richard Dunn, who also wrote the music for “The Spirit of Aggieland.”

Former Associate Band Director Col. Jay O. Brewer ’81 said, “It’s very long, drawn out; it crescendos up and then down. You can almost feel it.”

Dividing the music into three parts “gives it more depth of sound, and you can hear all the parts clearly, the low and the high part, and the middle,” Brewer said.

From the late 1920s into the 1950s, “Silver Taps” was also played to signify the end of the semester or the school year.

In fact, Dunn said “Silver Taps” was first played on the night of 1929’s Final Ball, according to a 1951 Battalion article.

1930s: The Ceremony Takes Shape

By the end of the 1930s, “silver taps” at A&M had become a full-fledged ceremony called Silver Taps, held at night in the Academic Plaza with students gathered in silence.

An essay written during the 1937-38 school year captures the event, much as we know it today.

Joseph G. Rollins, Jr. ’38 wrote that at 11 p.m., the plaza area “is luminated by intermittent lights”; “the dead boy’s company stands at attention” and there is silence as six trumpeters at the base of the Academic dome play to the north, west and south.

Then, rifles boom as the cadet’s company fires three volleys; the smoke “is visible when mirrored by the lamps near the walk.”

The company orders arms, with the command spoken softly, and marches silently back to the dorm as groups of attendees disperse.

1940s-70s: ‘Who Is An Aggie?’

After World War II and into the 1950s, many A&M students were “civilians”: mainly veterans or students who had left the Corps. School traditions like the Aggie Ring and Silver Taps were regularly extended to these students.

Then in the 1960s, Texas A&M’s student body began to grow rapidly once women were admitted (1963) and men’s participation in the Corps became voluntary (1965).

Students discussed whether honors like Silver Taps would be extended to them, as well as to other types of students, such as part-time students.

The debates persisted until 1971, when the Student Senate voted that Silver Taps belonged to all Aggie students.

One comment summed up the majority view, according to the Feb. 26, 1971, Battalion: “Are we going to sit here in the Student Senate and decide who is an Aggie and who isn’t?”

The only qualification set was that the Aggie must be “currently enrolled.”

1979: Shift To First Tuesdays

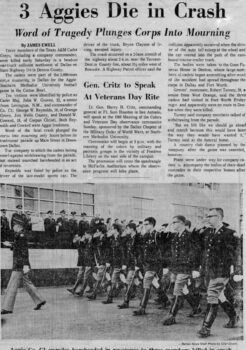

As A&M grew, Silver Taps was held more often, with car crashes becoming the most common cause.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Silver Taps was still conducted as close “as possible” to the student’s passing, frequently on a Monday or Tuesday after a weekend death.

At the same time, student enrollment more than quadrupled from 7,046 to 31,331 (1960 to 1979).

In fall 1979, Silver Taps was held four times in nine weeks.

Aggie students debated: Would limiting Silver Taps to a once-a-month observance diminish the honor, or preserve it?

Some reasoned that having the ceremony so frequently reduced attendance, and that setting a designated night would decrease conflicts with other school events. Others felt that each Aggie deserved a ceremony, or that delaying could put friends and families through a second period of grief.

On Dec. 5, 1979, the Student Senate voted 49-25 to hold Silver Taps on the first Tuesday of the month when needed, and so it has been ever since.

‘Dear Mom & Dad’

Tens of thousands of A&M freshmen since the 1980s have learned about Silver Taps before they even reach campus — at Fish Camp when a young Aggie’s letter home is read aloud.

The story began with a member of the Corps of Cadets sitting at his desk. In the fall of 1968, after attending Silver Taps on Oct. 22, Corpus Christi freshman Don Coward ’72 sat down and started a letter to his parents. “Right now it’s 11:00 and Call to Quarters is over, I should be in bed, but there’s something I have to tell you both first,” he wrote. “I’ve experienced tonight what A&M is all about.” His letter gives a clear, heartfelt description of the Silver Taps ceremony, nearly identical to the way Aggie students experience it today.

On Nov. 12, Silver Taps was held again — this time for him and two fellow cadets.

The letter written by Don Coward ’72:

Dear Mom & Dad,

Right now it’s 11:00 and Call to Quarters is over, I should be in bed, but there’s something I have to tell you both first. I’m sitting here at my desk with tears in my eyes and thinking more about life itself than I ever had before. I’m not crying because of all the hell I’m going through – but rather because I’ve experienced tonight what A&M is all about. Mother & Dad we’re one big family up here and now I know what it means to be an Aggie. Tonight was “Silver Taps.” In case you don’t know what that is, I’m going to tell you & you’ve got to listen. Anytime a student here loses his life – no matter how – on an assigned date soon afterwards we have what you call Silver Taps. Everyone puts on civilian clothes and goes to the Quad in front of the administrative building and stands around a flagpole on which all the names of students from A&M who died while attending school here are listed. No one says a word from 7:30 at night until the next day. All is quiet & all the lights on campus are turned off. You have to put blankets up over your windows & even the coke machine lights are covered. The whole campus is a blanket of darkness. Then at 10:30 while everyone is at the Quad, a firing team fires a 21 gun salute in honor of those who died and the buglers play Taps and it’s over. Tonight I experienced one of the most solemn feelings I’ve ever had and feel so good inside. Mom, Dad it was just like God Himself was there with us. Well I guess you’re wishing I would grow up and quit coming on like this, over Silver Taps – but it was so, hell I can’t even tell you how it was, there’s nothing else like it. Well I’ve got to go now, it’s late & I need the sleep. Y’all be careful & I love you both.

D.C.

Teaching The Tradition At Fish Camp

Each summer, on one night of every Fish Camp session, freshmen gather in the main meeting room to learn about some of A&M’s more solemn traditions.

This program is put on by the students in Fish Camp Crew, who execute the camp’s set-up and behind-the-scenes work.

As the freshmen come in, “you can tell that they’re excited from their really busy day,” said Liz Springs ’16. “By that point they’ve really made some friends.” But the room quickly quiets.

Onstage, a cadet sits at a desk, writing while the letter is read aloud. It’s presented without a date, as a timeless event, “so it’s applicable to every freshman,” Springs said.

Next, the freshmen are told of the fatal accident. The sounds of Silver Taps follow. The presentation continues with Muster history and includes the names of those killed in the 1999 Bonfire collapse.

“When they leave, no one has to ask them to be quiet,” Springs said, “because they’re all so moved by the program.”

Connected To The Past

The Class of ’69 has sponsored Fish Camp Crew since 2009 partly because of this presentation. But it wasn’t until 2014 that they realized it was connected to a deadly car crash their senior year.

In fall 1968, the A&M Corps made a trip to Dallas for the Nov. 9 game against SMU, some attending a Friday night dance at Texas Woman’s University in Denton.

Early Saturday morning, a car carrying Coward, fellow C-1 freshman George W. Reynolds ’72 and C-1 commander John W. Groves ’69 ran head-on into a truck on a highway west of Roanoke.

Grieving cadets opted to go on with the Corps march just a few hours later down Dallas’ Main Street, playing “Silver Taps” before they stepped off. Larry Lippke ’69, who directed the Taps team, still recalls the sound of the three-part trumpet harmony echoing off the tall buildings around them.

Four nights later, Aggies gathered on campus to hold the full Silver Taps ceremony for their comrades.

Coward had written only weeks before: “The whole campus is a blanket of darkness. Then at 10:30… a firing team fires a 21 gun salute in honor of those who died and the buglers play Taps and it’s over.… Mom, Dad it was just like God Himself was there with us.”

Creating A Memorial

Moved by the story, the Class of ’69 began researching Silver Taps and Coward’s letter in 2014, eventually leading to the creation of the Spirit Plaza dedicated in 2019 on A&M’s Academic Plaza.

This plaza features a Silver Taps marker with a replica of Coward’s letter, alongside the Silver Taps bugle sculpture and Muster candle sculpture relocated from their previous Academic Plaza sites.

With this monument, Coward’s words and story have taken a permanent place at the heart of Texas A&M.

A Stirring Photo

The Association of Former Students received the following letter from Michael Ward ’88 in September 2019 after this 1987 photo appeared in an issue of Texas Aggie magazine:

I recall both woefully and fondly my memories of an Aggie Silver Taps on a Tuesday in early February 1987, and the memories of my brother Stephen. He was an Aggie. A resident of Crocker Hall. A member of the Class of 1990. And the first Class of ’90 member to die.

I woke up early Tuesday morning in room 230 of Crocker Hall. I walked the campus that morning. Quietly, alone. I attended class. I studied. I met the families of the others who had died since the previous ceremony in late ’86. And I prepared to attend Silver Taps. While I had attended previously as a student, I had never personally known someone who had been so honored. I knew what Silver Taps was, but I did not understand what it meant to the family of the fallen.

I invited my family to join me for Silver Taps that Tuesday. I invited them. But, they did not come. I was left alone, the only member of my brother’s family to attend his Silver Taps. But I was not alone. The students and faculty of Texas A&M joined me.

The Aggie Corps of Cadets honored and respected my brother and his memory. My friends from Crocker Hall where my brother and I both lived, the family members of the other fallen students, and the Aggie student body stood silently alongside me as the bugles sounded, as the rifles fired.

I remember so well how, after the echo of the final shot faded and the last bugle call silenced, my Aggie family in attendance departed in complete silence, across the campus, back to their cars, back to their dorms. The Texas A&M campus was in complete silence, darkness and respect. They did this for me.

I remember this like it was yesterday.

Yet, it was 32 years ago, and I now understand what Silver Taps means.

All of these thoughts came flooding back to me one evening when, while turning the pages of Texas Aggie, I saw a photo I recognized. This was one of the photos included in your “Service & Respect” article [March-April 2015], which showed the Aggie cadets and students reading the Silver Taps announcement board.

This was not only a photograph of an announcement for a Silver Taps, but it was the announcement for the Silver Taps. For, on this announcement board in this photo was the name of my own brother, my flesh and blood. Gone, but not forgotten.

The issue of the Aggie yearbook from which you took this photo listed my brother, along with many others who passed that year. Yet, the book did not list the date of my brother’s death. I suppose the editors just did not have it. I will add it now.

Stephen Ward ’90. Dec. 27, 1986.

Thank you, Texas A&M University. My deepest thanks and gratitude to those who attended that night, and to the cadets and student body who maintain this tradition. Thank you for the support and the memories.

Michael Ward ’88

Cedar Park, Texas

Association Support For Silver Taps

Gifts made to The Association of Former Students provide financial support to Texas A&M’s Division of Student Affairs, which houses the organizations that conduct Silver Taps. Donations to The Association also help pay Ross Volunteers expenses including purchase of uniforms, and The Association prints informational and keepsake materials for the honored families. Add your support.

Continue reading and hear “the sounds of Silver Taps” from The Association of Former Students.

Media contact: Sue Owen, sowen94@aggienetwork.com