What You Should Know About April’s Cicada ‘Double Emergence’

As temperatures rise this spring, parts of the United States will witness a natural phenomenon that occurs only every 221 years, as two neighboring broods of periodical cicadas — Brood XIII and Brood XIX — simultaneously emerge from the ground to search for mates.

Beginning around late April, billions of the flying insects will spread across parts of the American South and Midwest, making lots of noise but posing little threat to humans and plants, said Molly Keck, an entomologist and Integrated Pest Management Program specialist with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service. While these particular cicadas won’t be seen in Texas, Keck said this rare double emergence event represents a great opportunity for people across the country to learn more about the insects and their unique life cycle.

“Anything that makes people interested in insects for reasons other than trying to kill them is always a plus,” she said. “If it helps people learn a little more about cicadas, then that’s a good thing.”

What Are Periodical Cicadas?

Texans are likely familiar with annual or “dog-day” cicadas, the green-and-black insects that emerge each summer across large swaths of the state, leaving their exoskeletons on tree trunks and other surfaces, Keck said.

Though part of the same family of insects, “periodical cicadas” differ from their annual counterparts in appearance and behavior, emerging only every 13 or 17 years depending on the specific species. This year’s historic emergence will consist of two adjacently located broods: Parts of the upper Midwest will see the emergence of Brood XIII — a group of 17-year cicadas that last appeared in 2007 — while the lower Midwest and Southeast will welcome Brood XIX, 13-year cicadas not seen since 2011.

The last time these two broods were above ground at the same time was in 1803, and they won’t co-emerge again until 2245.

The geographic ranges of the two broods are mostly separate, Keck said, with only a small area of potential overlap around central Illinois. Still, she said the rare alignment of their 13- and 17-year life cycles could make for an impressive number of the distinctive insects spread across a large swath of the continental U.S.

“Time is going to tell on that,” Keck said. “I’m curious to see what the actual numbers look like.”

While they are mainly harmless, Keck said periodical cicadas have sometimes been known to break tree branches by landing on them in large numbers. In addition, she said people in affected areas should get ready for a noisy few weeks as male cicadas emit their signature chirping sound to attract mates. Residents should also be prepared to remove piles of dead cicadas from around their property, as they can begin to stink when left unattended.

The Cicada Life Cycle

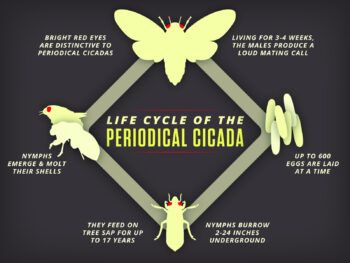

Humans witness just a small part of the cicada’s overall life, Keck explained, noting that most of the insect’s growth and development happens underground.

“They only have three stages to their life cycle: an egg, which turns into a nymph and then an adult,” she said. “Adults will lay their eggs, usually on the bark of trees, and when they hatch, the nymphs will crawl into the ground.”

There, the nymphs mature, feeding on the roots of trees and other plants; Keck says this behavior rarely causes damage to plants in Texas. How long they remain underground varies significantly, with annual cicadas spending two to five years below the surface and periodical cicadas remaining there for much longer, either 17 or 13 years depending on the species.

“(During those years), they’re just developing under the ground very, very slowly, and then they emerge as adults,” Keck said. Once they’re topside, mature cicadas scale the nearest tree or other vertical surface, where they shed their exoskeletons and take flight to search for a mate.

Compared to the years they spend as nymphs, adult cicadas have a very short lifespan, Keck said. Above ground, periodical cicadas live for just three to four weeks, while annual species can live for five to six weeks — just long enough to fertilize and lay their eggs, starting the cycle over again.

While their brief appearances are sometimes described in apocalyptic or even biblical terms, with references to a “plague of locusts” or the “cicadapocalypse,” Keck says it’s important to remember that cicadas are not dangerous — and they aren’t locusts, either.

“Growing up, I called them locusts,” she said, explaining that the common misnomer is likely a regional phenomenon. “In reality, locusts are actually grasshoppers, so they’re not even in the same order. They are not very closely related insects.”

Media contact: Laura Muntean, laura.muntean@ag.tamu.edu