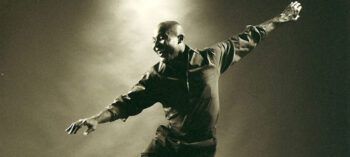

Elijah Gibson’s ‘Dance Of America’ Installation Celebrates Legacies Of Black Pioneers

Elijah Alhadji Gibson, assistant program director and lecturer in the Dance Science program, will present a multidisciplinary immersive event titled “Dance of America: A Celebration of Black Dance in the United States,” Thursday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. at the Black Box Theater in the Liberal Arts and Arts and Humanities Building.

The free event, hosted by the Dance Science program in the Texas A&M School of Performance, Visualization and Fine Arts, will feature an installation of about 60 artists with archived video footage and an interactive timeline, Gibson said.

In honor of Black History Month, Gibson said he is excited to showcase and celebrate Black dance history in the United States through the telling of monumental dance pioneers and companies, dance eras and movements.

“The work the Black artists were producing was a form of cultural affirmation and expression that developed from being in an oppressed state,” Gibson said. “It is socioeconomical, political, activism, educational and entertainment, all wrapped up into an experience. The hope is that each person who visits the installation will take advantage of the information made available to them and walk away with a newfound appreciation for the artists who were the blueprint for many of our favorite dance genres and forms.”

Participants will be able to view images of each individual artist — from modern-day to dancers of the past — and a QR code will link to more in-depth information, Gibson said. Genres include ballet, modern, jazz, hip-hop, musical theatre, house, tap, vogue and contemporary dance.

Featured artists include Chuck Davis, Dianne Walker, Will Robinson, Gregory Hines, Frankie Manning, Norma Miller, Ronald K. Brown and Joan Myers Brown. The hope is that participants will acquire knowledge about these dancers that may have otherwise been overlooked, he said.

“The goal is for visitors to learn about the legacies that have been overshadowed by the fact that these artists were not allowed in spaces that would have given them the recognition for their labor and their contributions,” Gibson said. “Without the contribution of these artists, dance would not have had the trajectory it has had. For future generations to truly embody dance in the fullness of all its complexities, we must establish the connections from the past to where we are now.”

Two movements — the Harlem Renaissance and the Great Migration — helped to influence Black dance at a time when access to certain spaces and resources weren’t allowed, Gibson said.

The Great Migration created “a space for Black intellectuals, igniting a cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, literature, politics and fashion,” he said. The Harlem Renaissance designated the area as a “safe space for Black artists to thrive,” Gibson said.

“Also known as the New Negro Movement, it inspired cultural expressions across urban areas in other parts of the country,” Gibson said. “It is so rich in history. If these movements had not happened and if these dancers had not sought and fought for liberation through cultural expression, I wouldn’t be able to do what I am doing now.”

Gibson recalled at age 11 meeting tap dancer Arthur Duncan at a tap festival in San Diego, which promoted the 1989 release of the movie “Tap.”

“Arthur’s style and quick feet resonated with me the most out of all the tap dancers I had encountered,” Gibson recalled. “Betty White gave Arthur his first job when he was featured on ‘The Betty White Show’ that aired in the 1950s. The network encouraged her to take him off because of the color of his skin, and she declined.”

Gibson also worked with choreographer Donald McKayle, who “was one of the first Black men to direct and choreograph major Broadway musicals,” he said. McKayle, who died in 2018, was known for creating socially conscious work in the 1950s, Gibson said, including his play “Games.” Gibson was cast as the character Jinx in a restaged version of the work.

“Being in the space with Donald is one of my most cherished memories as a dancer,” Gibson said. “Much to my surprise, I came in contact with him almost 15 years later at a dance festival in Palm Springs, and I was shocked when he remembered me.”

As a young dancer, Gibson said most of the spaces he trained in “had only white teachers,” and he was “always one of few Black students, if not the only one.” He revered instruction from Black dance educators, including Frank Hatchett, one of his favorite jazz teachers.

“I began taking classes from Frank when I was about 10 years old, and he was part of my dance training into my professional dance career,” Gibson said. “Throughout my time as a student and professional dancer, I was fortunate to have been in spaces with many of the artists people will see featured in the installation.”

Gibson hopes students who attend “Dance of America” will continue the legacy of dance by passing it on to others. He said he’s eager to hear feedback.

“The more we can keep dance history alive and relevant, and how it’s cross-referenced the political climate of the time, the better chance we have of establishing dance as a cultural significance in this country,” he said. “I am a dancer at heart. I think it is important for us to share our experiences, because only then can we begin to understand each other. And if we don’t continue to cultivate these exchanges, then we are never really going to understand who we are as a people.”

Media contact: Rob Clark, rob.clark@tamu.edu