How Often Do We Think About The Roman Empire?

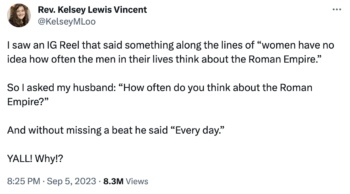

Despite its fall more than 1500 years ago, the Roman Empire resurges in the popular conscience every so often. For example, Gladiator (2000), one of the most financially successful films of the 2000s that won five Academy Awards, was inspired by Ben-Hur (1959) and Spartacus (1960) and went on to inspire several pieces of media, such as television shows Roman Empire (2016-2019), Plebs (2013-2019), Britannia (2017–2021) and many more. The latest homage to the Roman Empire has arrived in meme form.

What started as a social media phenomenon wherein spouses would ask their partners “How often do you think about the Roman Empire?” has now been covered by CNN, Wired, Forbes, Rolling Stone and others. The common denominator, which has surprised many, has been that people think about the Roman Empire quite a lot, actually. As such, we asked Texas A&M University history professor and late Antiquity/early Middle Ages expert Dr. Daniel Schwartz for his thoughts on why people think so much about the Roman Empire.

I have to ask: How often do you think about the Roman Empire?

As you can imagine, I think about the Roman Empire rather a lot. Almost everything I’ve taught for the last 15 years has included Rome in one way or another. Before that I was in a couple of different graduate programs where Rome featured prominently, my Ph.D. being focused on the Later Roman Empire. One of the interesting things about my sub-field, Syriac Studies, is the complicated relationship with Rome. The people who were a part of this culture and language group were on the border between the Roman and Persian empires. They spoke a dialect of an ancient Mesopotamian language, Aramaic. They were also deeply invested in theological debates in the broader Mediterranean world in which Rome played a significant role. What makes the Later Roman Empire so interesting to me is the engagement with cultures and languages on the periphery of the Mediterranean: Syriac, Coptic, Arabic, Armenian, Georgia, etc. In earlier Roman history, we rarely get a record of these voices and perspectives. I suppose it is fair to say that what I find interesting is looking at ancient voices who alternately desired a connection to Rome and also pushed back against its influence to maintain their distinct cultures.

How has the Roman Empire influenced modern societies?

The influence of Rome is considerable. From our civic architecture to our legal traditions, to our understanding of religion, philosophy, politics, etc., we live in a society that is intermingled with Roman traditions. We often are not aware of this, however. And we’re even less aware of how these ancient ideas were preserved and transmitted into Europe and from there into the Americas. Very often it was through Syriac- and Arabic-speaking Christians and Arabic-speaking Muslims. “Western civilization” as we know it is incomprehensible without the medieval Middle East. When we study the history, we see clearly that we are a long way from a monolithic Roman heritage that Europe simply inherited.

Has popular culture perpetuated misconceptions of the Roman Empire?

I think it is very easy to misunderstand the Roman Empire. Some want to see their own society as related to the glories of Rome: military strength, territorial expansion and influence, etc. Alternately, people often want to see in the “fall” of Rome a set of universal lessons about how to avoid the waning of their society. The idea seems to be that if we can understand how Rome became so prominent, we can apply those lessons to empower our societies and nations. Such emphases tend to focus more on social theory (assertions like, “successful human societies do x and avoid y”) rather than on history, which at its best is particular, deeply nuanced and thoroughly contextualized. I struggle to see Rome as some kind of shining example of past glories. Rome was a pretty nasty place for most people. Life expectancy was low. A huge percentage of children died in infancy or as toddlers. Slavery was ubiquitous and enslavers had near total control over those they enslaved. There was little to no social safety net. Poverty was widespread, as were various forms of violence.

Why do you think the Roman Empire is such a popular period for modern storytellers to revisit?

People like power and success, and they see Rome as having those things. People seem enthralled with the violence as well, with military conquest and with gladiatorial competitions. This is surely an important legacy of the Roman Empire. Many Romans were enthralled with this kind of violence. Both gladiatorial shows and military conquest served a propagandistic aim; they entailed rituals that enacted power. I’m afraid these ancient rituals of power over the bodies of marginalized people and states seem to capture the modern imagination just as much as they were designed to capture the ancient imagination. This modern obsession concerns me. I think that the study of different times and places should humble us. As we seek to understand a society like Rome, we should be forced out of ourselves. Such study should cultivate skills that help us appreciate differences between people, their cultures and their ideas. They should make us practiced at encountering differences in our own society and responding with understanding and empathy. An obsession with power, past or present, works against these aims.

Media contact: Reyes Ramirez, rvramirez@exchange.tamu.edu