Kyle: The Life And Legacy Of The Man Behind Texas A&M’s Football Stadium

It’s a name that’s hard to miss.

Spelled out in eight-foot-tall letters on one of the largest football stadiums in the United States, “KYLE” towers over Texas A&M University and Aggieland.

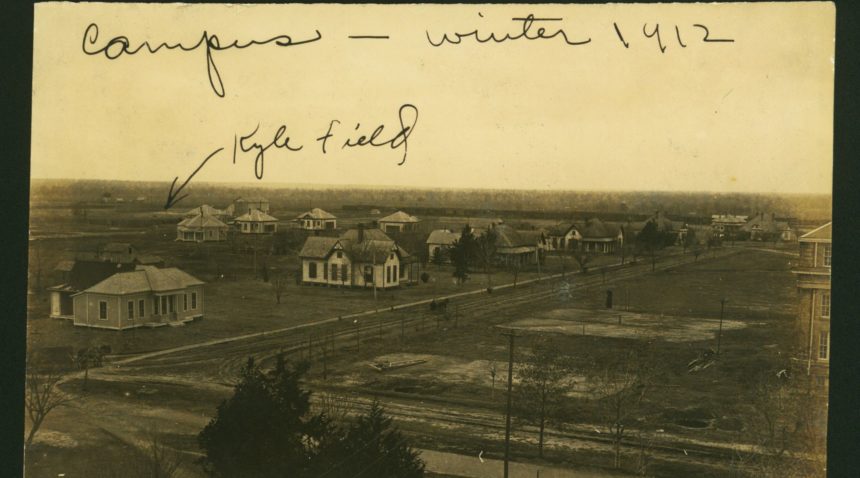

But the story of the man who gave his name to the home of Texas A&M football begins before the Aggies were called Aggies, and when College Station was just that — a train station near a small cluster of buildings in the middle of nowhere.

In 1896, a young Edwin Jackson Kyle stepped off a train at that station, ready to begin his education at the equally-young Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas. In the decades to follow, the fresh-faced boy from Hays County would become “Mister A&M” — a beloved and revered professor, long-time leader of the athletic council and the school of agriculture’s first dean.

While Kyle Field may be the most recognizable piece of his legacy, Kyle’s contributions to both athletics and agriculture run far deeper. Ultimately, his work extended well beyond Bryan and College Station, reaching all of Texas and even across continents.

“When you plant a tree, you won’t get to benefit from the shade — but someone else will,” said Jeffrey W. Savell, current dean and vice chancellor of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “Kyle was that type of person. He planted a lot of trees around here, literally as well as figuratively, and his impact is still reverberating to this day.”

A Town Called Kyle

E.J. Kyle was born the same year as Texas A&M, 1876, in a relatively undeveloped area of Central Texas. Around the time of Edwin’s birth, the small community of Kyle, Texas, began to spring up around the Kyle family’s home after Edwin’s father convinced railroad baron Jay Gould to direct his new rail line through their land.

Evidently, academics were not yet a strong suit for the young Edwin Kyle. He repeatedly failed the third grade and eventually dropped out of school altogether, finding work at a local candy shop for a while.

As he remarked to the Houston Post years later, “I was just a country boy and always in trouble. I was leader of a gang who did everything known to boys in those days like raiding watermelon patches and chicken roosts.”

Once he had settled down and finished high school, Edwin hopped on a train to join his big brother at college. Still a bit of a rebel, he broke with his brother and the rest of the family by choosing to focus on horticulture instead of ranching.

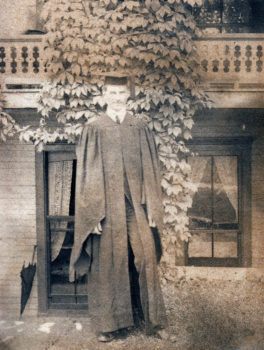

Though still in its infancy, A&M was full of opportunities, and it didn’t take long for the younger Kyle to distinguish himself. He rose rapidly through the ranks of the Corps of Cadets, ultimately becoming senior captain on top of his roles as class president, YMCA president and valedictorian of the graduating class of 1899. And an accident of history briefly placed Kyle in a position that no other student has ever held.

“The Spanish American War gutted our military staff and a civilian commandant was appointed, but he was stricken seriously ill,” he told the Houston Post. “As Corps Commander, I became Commandant until his recovery, a month later.”

Kyle was leaving his mark in other ways, too. In 1897, he teamed up with fellow cadets and Rita Sbisa, the daughter of A&M’s beloved chef, to create a bicycle path between the college and the nearby city of Bryan.

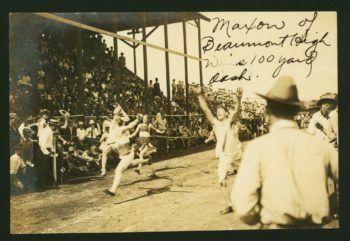

Back on campus, he ran track and helped manage the Football Association. At that time, there wasn’t much support for athletics among the administration; it was tolerated, but just barely. The meager state of the teams and a lack of permanent athletic facilities reflected that fact.

Kyle would aim to change all that when he returned to campus just a few years after graduation.

The Field

When Kyle rode the rails back to A&M in 1902, he brought with him a new perspective on the state of his alma mater.

Kyle had studied in New York at Cornell University thanks to funding from a wealthy, well-connected cousin. In addition to his master’s in agriculture, Kyle received a crash course on the stark disparities between northern and southern schools, and the dire need for better agricultural education in his home state.

After graduation, he took a tour of the north’s top agricultural colleges and accepted a job back at A&M, determined to surpass them all. His first year back, he became head of the horticulture department and began working at the agricultural experiment station.

“E.J. Kyle never wavered in the belief that it was his personal responsibility to upgrade the agriculture of rural Texas, then a backbreaking enterprise totally dependent upon the forces of nature,” said friend and collaborator E.R. Alexander in a 1970 interview. “He seemed to take on the personal welfare of each of the state’s farmers as his own special burden.”

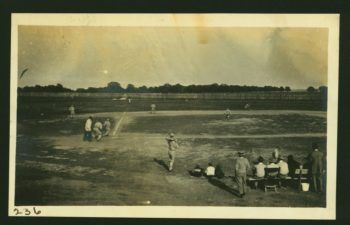

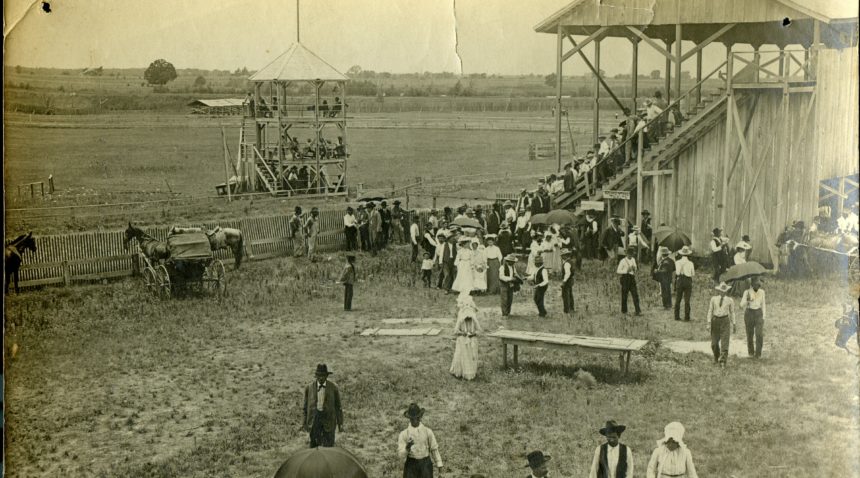

Now “Professor Kyle,” 26-year-old Edwin found campus much as he had left it — especially where athletics were concerned. Without a dedicated athletic field, sporting events were held on the drill field, with spectators standing off to the side or parking horses and buggies nearby to watch the action.

Kyle was a fixture at games. As business manager of the college’s newly-formed General Athletic Association, he could often be found walking up and down the sidelines with the coaches and cadets. In 1903, he was seen watching from the seat of his buggy next to Alice Myers, the woman who would become his wife.

As time went on and Kyle worked his way up in the athletic association, he became convinced that if the college’s teams wanted to achieve any real measure of success, they would need a new home — a field designated specifically and exclusively for athletic events. Kyle had just the spot in mind.

In his role as head of the horticulture department, he oversaw large swathes of campus farmland set aside for agricultural experiments. In 1904, Kyle went before the college’s board of directors and got permission to repurpose some of that land. Pretty soon, “Kyle’s field” was the site of baseball games, football contests and other athletic competitions.

“They used the field because it was there,” said Barbara Donalson, Kyle’s biographer and great niece. “It was just a blank space that his agriculture students used for their projects. It wasn’t Kyle Field, it was just Kyle’s field.”

Mister A&M

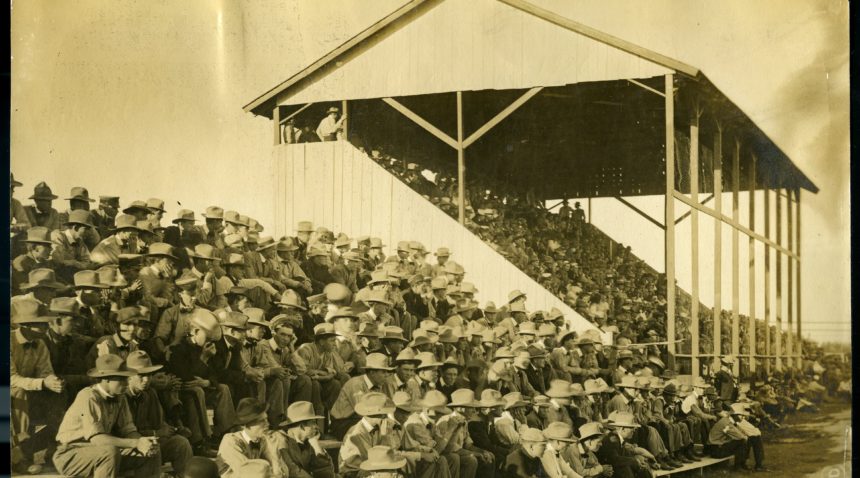

The first major addition to the new athletic field came in the fall of 1905 — a set of wooden bleachers capable of holding 500 spectators. Professor Kyle bought the lumber.

That same year, the A&M College “Farmers,” as they were called, played their first football game on the field, clobbering a team from the Houston YMCA 29-0. Kyle was now president of the athletic association, and he began his tenure in a big way: standing up to the state university in Austin by changing the letter on A&M athletes’ chests from the somewhat diminutive “C” for “College” to a “T” for “Texas.”

Kyle was something of a rarity for the time, departing from the prevailing position among administrators that athletics was nothing more than a way to keep the cadets in good physical condition. On the contrary, Kyle saw sports as a vital component of the college’s mission and a key to building its reputation as an institution.

“He knew athletics meant more to cadets,” Donalson wrote in “Kyle Tough,” her 2011 biography. “Sports helped to keep the prank-prone students out of trouble. Most crucial of all, he believed athletics would add status to A&M as a complete college.”

Sure enough, as Kyle Field and the athletic program continued to develop, so too did Kyle’s influence as an educator and the power of the college as a whole. Years passed, and Professor Kyle became well-known across the state for his efforts to bring scientific farming to the people.

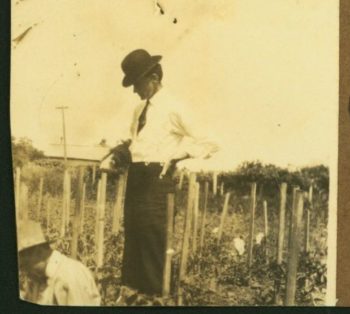

Day after day, Kyle measured the success of new crop varieties and growing techniques, publishing his findings in official bulletins and traveling across Texas to deliver in-person speeches and demonstrations.

“Extension work helps many poor farm families,” Kyle once wrote to a county agent. “They respond to our demonstrations by raising better gardens and canning more food.”

Some of Kyle’s early work included efforts to improve dewberry and blackberry yields, along with a state-wide campaign to combat the notorious boll weevil threatening Texas cotton fields.

But it was his work with nuts that would make Kyle a true hero of the state’s planters.

Sensitive to the hardships wrought by Texas droughts, he set about finding a crop that could thrive under such harsh conditions. As The Bryan Eagle reported in 1907, Kyle soon found success with peanut plants.

“On what is ordinarily known as poor sandy post oak soil, and in spite of an unfavorable growing season, Professor Kyle succeeded this year in growing two good crops of peanuts,” the paper declared. “Despite the fact that there was practically no rainfall during the growing season for the second crop, the peanuts made a good yield. It is pretty hard to overestimate the possibilities of the peanut on the thin lands of Texas.”

Kyle also worked to develop an improved variety of pecan, fatter and meatier than the small, thick-shelled nuts which fell from the state’s native trees. He soon found that he could graft his new variety onto these existing trees, and over the following decades, Kyle’s pecans spread across Texas and much of the South.

“The nutritious pecans became a staple of most kitchens, and a star ingredient in holiday recipes,” Donalson wrote. In fact, one holiday season, members of the news media opened their mailboxes to find a personal gift from E.J. Kyle — a tin of his pecans meant to showcase their superior size and quality.

All the while, A&M College was increasing in size and prestige. In 1911, the board decided to split the growing faculty into the schools of engineering and agriculture. When it came time to name a dean for the latter, Kyle was the natural choice.

He held the role for over three decades, overseeing a period of exponential growth and development. By the time he retired in 1944, A&M’s ag school was the largest in the nation.

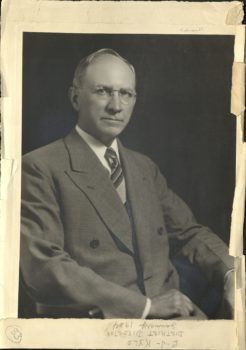

“He was probably the perfect dean to have to start this process back on day one,” said Savell, who started as dean earlier this year. “His portrait hangs in our main hallway here, and there’s not a day I walk by there that I don’t look at it.”

Incidentally, Savell’s new office also came with an excellent view of Kyle Field — a constant reminder of his predecessor’s lasting service to the university. “That’s an example of the kind of person he was,” Savell said. “He was here for the institution above and beyond just being a dean.”

Sure enough, even rising to the position of dean was not enough to tear Kyle away from athletics — though it wasn’t for lack of trying. Kyle had already attempted to resign as chairman of the athletic council once before, but was stopped when the entire student body signed a petition asking him to stay.

In 1911, his resignation was reluctantly accepted, giving the newly minted dean some much-needed time to focus on his growing array of responsibilities. But by the mid-1920s, Kyle had been pulled back into the affairs of A&M’s struggling sports teams.

Navigating financial hurdles and disputes between coaches, players and administrators, Dean Kyle hit the peak of his managerial prowess in 1939, when the Aggie football team clinched both the Southwest Conference championship and their first-ever national championship.

“If a willing spirit can prevail on this club this year, no team can stop you,” Kyle told the ‘39 Aggies in an early-season pep talk. The speech was transcribed and distributed around campus, helping build support for the team’s successful championship bid.

Kyle was reluctant to take much credit for the winning season, choosing instead to extoll the determination of the players and the leadership of coach Homer Norton.

“The boys are like just so many brothers,” Kyle said of that year’s team. “Take Bill Conatser and Derace Moser for instance — they are roommates and they play the same position. Ask either, and he will swear the other is the better player.”

Though it was a time of celebration for the Aggies, the United States was still facing numerous challenges as it emerged from the Great Depression and anxiously observed the outbreak of the Second World War.

During the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Kyle continued to make a name for himself, directing A&M’s efforts to assist struggling producers and working for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Farm Credit Administration.

A 1941 article in the Dallas Morning News called Kyle “the only living man in Texas to have the complete confidence of both the state’s dirt farmers and its cattlemen.”

Perhaps that’s why “Mister Texas A&M,” as the press and others had taken to calling him, was soon asked to leave Texas behind and put his people skills to work as a foreign diplomat. During his later years as dean, Kyle had become increasingly interested in Latin America, working to strengthen agricultural ties between the U.S. and its neighbors to the south.

“Your trip was beneficial because you visited and talked to the rural people, the working-class, the farmer and the stock raiser,” fellow Aggie J.E. Millender ’12 wrote to Kyle about a visit he made to Brazil. “No Brazilian can even remember the names of the committeemen sent down here. On the contrary, every damned man in this state remembers Dr. Kyle and how ‘simpatico’ he was.”

In 1945, Roosevelt appointed Kyle ambassador to Guatemala, where he formed a relationship of mutual respect and admiration with the nation’s first democratically elected president, fellow academic Juan José Arévalo Bermejo.

In a letter to Kyle in 1946, the former philosophy professor praised the retired A&M dean for his “finely sensitive nature… deeply rooted democratic convictions… (and) noble sentiments of affection and understanding” for his country and its people.

Upon his departure as ambassador in 1947, Kyle became the first American awarded the Order of the Quetzal, the nation’s highest honor. He returned to his home on South Bryan Avenue and enjoyed a busy retirement until his death in 1963.

The Man In The Long Black Car

When Barbara Donalson thinks of her great uncle, there’s one story that comes to mind. To her, it shows that despite all the accolades and fancy titles, the thing Kyle cared about most was people.

She still remembers watching “Uncle Ed” step out of a long black car and walk up to the house to attend a family gathering — pausing for a moment to speak with her and the other kids.

“A lot of people ignored us, but he didn’t,” Donalson said. “He talked to me in the third grade like he talked to grandmother when she was in her 60s. He knew what each person was interested in, and he went there.”

Even today, Kyle’s love for people and his commitment to improving their lives can still be seen in his work as an agriculturalist, a sports manager and a diplomat.

Ultimately, Savell said, it’s that same commitment that forms the foundation of Kyle’s enduring legacy at Texas A&M.

“We are called to be of service to the people of the state, and I really think that was something E.J. Kyle helped foster,” Savell said. “It’s all part of the process, part of who we are. When I think about the people that are in our college, we have that as our roots.”

Media contact: Luke Henkhaus, henkhaus@tamu.edu