Women’s Movements And Youth Form Strong Alliance In Fight For Iranian Civil Rights

The Iranian people want to cast off unjust laws enforced by the country’s religious dictators and so called “morality police” who use their version of Islam as a weapon to oppress women and maintain power. But recent protests are showing the “TikTok generation” and Iranian civil rights activists who have been resisting for decades are banding together to fight for civil liberties.

That’s according to Texas A&M University’s Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar, a professor of international affairs at the Bush School of Government and Public Service and former BBC reporter, whose political commentaries have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Foreign Affairs and other national outlets.

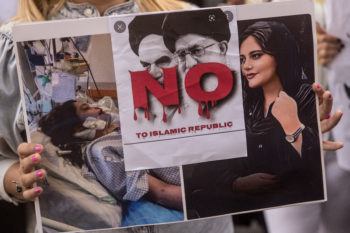

Tabaar, who was born in Iran, said recent protests following the killing of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini for the “crime” of showing her hair in public should serve as a wake-up call against common misperceptions, like that Iranian citizens, including women – and Muslim women in general – have been made to be submissive.

Tabaar says Iranian women may or may not want to cover their hair – what they really want is the freedom to choose, and their efforts over the past four decades are proof of that.

In The Wake Of The Revolution

Iranians – women and men alike – have been resisting autocracy in large and small ways both before and after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, when it was believed a more democratic society would emerge. Instead, the Islamic Republic of Iran rose to power and imposed a set of rules under the banner of Sharia Law. Sharia laws include mandatory hijab, but also other discriminatory practices including restrictions for women on marriage and divorce, child custody, inheritance and travel.

Tabaar, who teaches a graduate seminar on religion and politics in Iran, says those laws have nothing to do with the actual tenets of Islam and everything to do with political power.

“Many of those who are protesting today may not even remember that when the revolution happened 43 years ago, it was not about religion but to bring independence from foreign interventions and freedom to Iranians,” he said. “But as the revolution succeeded, those who came to power needed to establish an identity to form an exclusive government. So if you’re ruling in the name of religion – in this case Islam, or so they say – instead of bringing about justice, equality and economic prosperity, all of which are difficult to do, they claimed they were implementing Islamic law.”

The first step for a religious dictatorship like the Islamic Republic to maintain power is to control women, Tabaar said. “The way you show you have an Islamic State is to force women to veil,” he said. “Initially, they were very cautious saying women should just be modest. The women would get lax on veiling and the regime would let it go for a while but would eventually crack down again. And it would go back and forth. Then the regime started sending these thugs, basically, to enforce their rules, and then institutionalized them into the ‘morality police.’

“But this proved to be a formidable battle for the state,” he added, “as women showed resistance both in professional settings and as ordinary citizens on the streets on a daily basis.”

Iranian women may or may not want to cover their hair – what they really want is the freedom to choose

In mandating hijab, the regime was also trying to silence the non-Islamist clerics who were apolitical and saw the Islamist regime as heresy. “The traditional clergy could pose a serious legitimacy crisis to the Islamic Republic,” Tabaar said. “That was one of the reasons the new state enforced these rules, so it could increase the cost of dissidence in religious circles by saying ‘What’s your issue? We’re forcing women to veil so we’re Islamic.’ It was about regime survival and consolidation, not necessarily about religion.”

He continued, “What the Quran says about veiling is open to interpretation. But even if we agree that coverings should be worn based on the Quran, there is nothing that says the state has to enforce it, according to many religious scholars. That’s actually undermining the basic tenets of Islam by forcing people to do things they do not want to do.”

And in fact, about 70 percent of Iranian women do not veil according the state’s strict dress code, Tabaar said, “so that gives you an idea of what women actually want.”

Ironically, this trend is the opposite of the pre-revolutionary era in which many women would veil to protest against the secular monarch, whose father had forced women to unveil almost a century ago as part of his grand plan to establish a modern nation-state in Iran. “Women’s bodies are often a marker of the state identity,” Tabaar said.

A New Generation Of Freedom Fighters

Tabaar said abuses by the morality police have ranged from harassment on the street to beatings and killings, most of which have not been as highly publicized as the killing of Amini. Her case has been so well publicized, he said, for two reasons: one is that Amini’s family came forward, which many Iranian families fear to do when a loved one is killed by the morality police. And second: social media.

Could today’s social media-savvy youth gain the freedoms their parents and grandparents have not?

“The younger generations, especially young women, have witnessed their mothers and grandmothers suffer,” Tabaar said. “They know this could go on for another 40-50 years, so they’re rebelling, they’re angry and they don’t want to put up with it.”

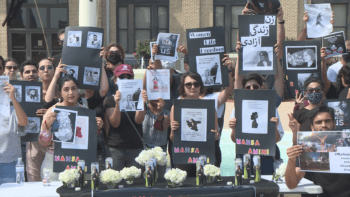

As with other civil rights movements such as the Arab Spring, #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, social media is playing a huge role. “This is the ‘TikTok generation,’ they have the power, literally in the palm of their hands, to form their own views and gain worldwide support for Iranian civil rights,” Tabaar said.

And it already seems to be working. Videos of women taking off and sometimes burning their hijabs are being viewed millions of times worldwide. Artists inside and outside of Iran are creating graphics, videos and photos that are going viral. And women around the world are showing solidarity by cutting their hair.

Nevertheless, Tabaar warns that states have shown remarkable capacities to use social media to their advantage too, by spreading misinformation and sowing discord among the protesters.

Very Cautious Optimism

Tabaar would love to say this latest wave of protests is going to succeed in winning the people of Iran their civil rights, but he knows how much stands in their way.

“In previous social and political movements, the state usually cracked down – quickly, immediately, brutally. And then when things calmed down, it started making minor concessions,” Tabaar said. At least 200 people have been killed so far.

“In the past, they would show tolerance for partially veiled women, as long as it was not politicized,” he continued. “But now it has become politicized, where women are taking off their hijab as a display of rebellion. So it won’t be as easy for the regime to make formal concessions to reduce tensions and hope the protests fizzle out. Although, there are reports that the morality police have been removed from the streets now in order not to further provoke the population.”

Another factor in the protestors’ favor is that even women who choose to wear hijab are supporting those who don’t. “A lot of veiled women are on the forefront of this because they want it to be a matter of choice,” Tabaar said.

With both veiled and unveiled women banding together with Iran’s youth population and gaining worldwide support, Tabaar said he is hopeful but cautious.

“These public unveilings are expanding, and Iranians abroad are organizing, so it is a hopeful scenario,” he said. “But the government can’t let this go on forever and it could become even more violent. What they are hoping is it just blows over and they can go back to the way things were.”

Last week, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei spoke for the first time about the Amini killing, criticizing the protesters and blaming the United States and Israel for planning the uprisings.

“What I think is most important for Americans and the rest of the world to know is that Iran is a country whose people want to live normal lives,” Tabaar said. “But they are caught between internal repressions and external pressures. They are fighting a viciously oppressive regime and have been for over four decades. And they are doing so, not because of the U.S. sanctions against Iran, but despite these inhumane collective punishments. The rest of the world is just catching up.”

Media contact: Lesley Henton, lshenton@tamu.edu