Using The Power Of Light, Researchers Are Studying Cancer-Causing Bacteria

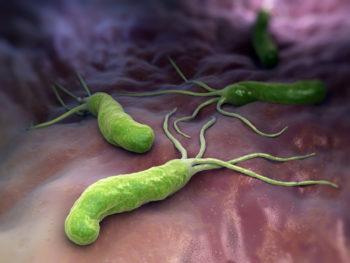

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) have colonized the stomachs of billions of people worldwide. Once an H. pylori infection occurs, it is challenging to eradicate.

This is a significant biomedical problem, as H. pylori can promote stomach ulcers and gastric cancers. How H. pylori navigate and colonize specific niches in the stomach remains largely unknown, but addressing this gap in fundamental knowledge is crucial for preventing infections moving forward.

Pushkar Lele, associate professor in the Artie McFerrin Department of Chemical Engineering at Texas A&M University, recently received an R01 research grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences totaling over $1.3 million to investigate the mechanisms that enable H. pylori to navigate with the aid of motility appendages called the flagella. To do this work, his group will combine experimental techniques such as optical trapping and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) with computational modeling.

Inside a bacterium, rapid signaling reactions constantly occur to control its movements. Measuring these reactions is the key to understanding H. pylori’s navigational strategies. However, such measurements are incredibly difficult inside a bacterium considering its minuscule size — a couple of microns – and the speed at which it moves – almost 30 times its length per second.

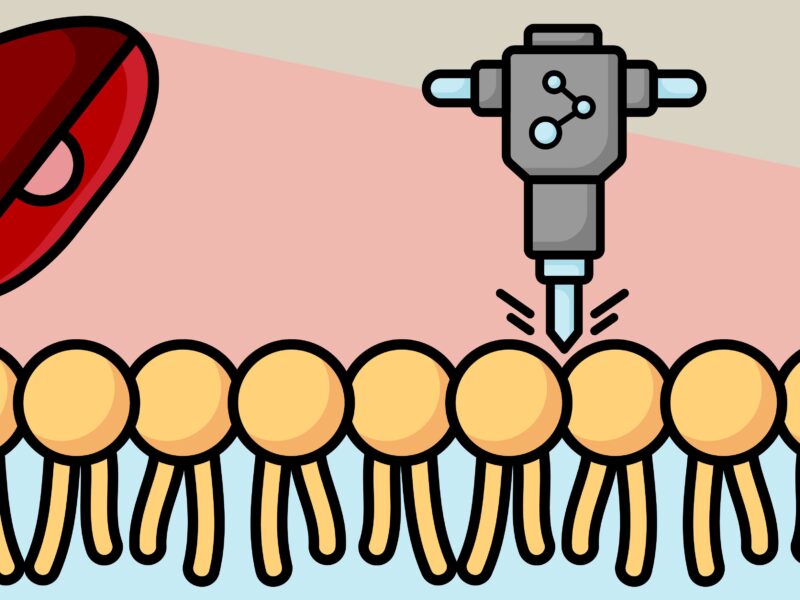

Lele’s group proposes to overcome the challenge by manipulating single bacterial cells through the power of light. Using what is known as an optical trap, the researchers will catch hold of single H. pylori cells and release them at distinct separations from their chemical targets to observe their navigational strategies. They will develop FRET assays to visualize signaling interactions in these cells.

“Bacteria rely on numerous signaling mechanisms to adapt their behavior to environmental conditions,” Lele said. “The pathway we are interested in specifically helps them migrate from an unfavorable location to a favorable environment — a process known as chemotaxis. How do H. pylori sense and respond to environmental cues despite appearing to lack key enzymes in their arsenal? There has never been a more opportune time to tackle these important questions in collaboration with renowned research groups in the field.”

The proposed work will build on the group’s previous efforts funded by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. In a study published in eLife last year, researchers developed a novel method to quantify the effect of the environment by exploiting fluid drag on each bacterium. Their approach helped them characterize the properties of individual motors that operate the flagella.

“The manner in which H. pylori swim causes them to retrace their movements every other second, nullifying the progress they might have made in the preceding second. This complicates the understanding of chemotaxis,” Lele said.

The group plans to tackle these questions by combining experiments with theory and computation.

“Their movements are erratic,” Lele said. “Nonetheless, they can be computationally simulated with adequate inputs from experiments. Rigorous experimental tests of their mathematical models are expected to help unravel major mysteries and predict the probability of infections in the future.”

The proposed research is timely as studies have shown an increased resistance in H. pylori to standard treatments. If the principles of navigation can be understood using these methods, there is potential to discover better ways to eradicate or treat H. Pylori infections.

“As H. pylori continue to become resistant to antibiotics, such mechanistic studies on the different facets of host invasion and colonization will address critical medical needs,” Lele said. “Chemotaxis strategies are well understood in only a few bacterial species, and successful execution of our projects will provide insights into the diverse strategies employed by pathogens to evade our immune systems.”

This article by Michelle Revels originally appeared on the College of Engineering website.