Texas A&M Professor Uncovers 1,300-Year-Old Murder Case

Qian Wang, a professor of biomedical sciences at Texas A&M University’s College of Dentistry, recently helped uncover the mystery of 1,300-year-old murder – and cleared the victim’s name.

His discovery is reported in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. Wang is the lead author of the paper detailing his sleuth worth. The mystery began in 2002 when construction crews in the Ningxia region of China discovered an ancient tomb. Several years later, archaeologists discovered a male skeleton in a large shaft leading down into the tomb.

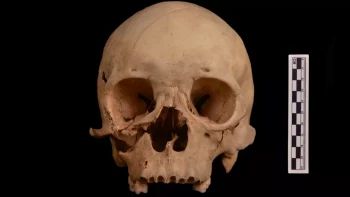

The shaft where it was found would have been dug by grave robbers, leading to a theory that the man died while trying to raid the tomb. But Wang’s review of the skeleton suggests that the man was, in fact, a murder victim.

In 2019 the remains were screened for bone pathology and trauma, which revealed several scars across the man’s face and body, indicating he was attacked with a sword, Wang said. A fracture in the man’s forearm suggests that he held his arm out in an attempt to defend himself from the attack.

“Looking at all these nasty kind of injuries on his skeleton, he died of assault,” Wang said. “He wouldn’t be part of the original robberies. But who was this guy, and who assaulted him? Just one guy or a group of people? That information is lost to history.”

According to radiocarbon dating, the man was killed about 1,300 years ago. However, the tomb and its original occupants are 700 years older, dating to the Han Dynasty era. It is unlikely a grave robber would attempt to steal from a tomb that old, which already showed signs of being robbed, Wang said.

The man was killed, and his body was thrown down the shaft to hide the evidence, Wang said. Hiding a body in a grave robber’s shaft would be akin to “hiding a leaf in the forest.”

“Long story short, we figured out this was definitely a homicide case,” Wang said. “His body was dumped over there to avoid sighting and punishment.”

The tomb held three occupants: a man, a woman and a child. Wang said scarring on the man’s skull suggests he had a tumor of some kind.

He also observed that the size of the shaft dug by the grave robbers suggested a high level of organization. It was too big for just one person to dig on their own, he said, and likely was a group effort. The robbery could have been sanctioned by military leaders or warlords looking for treasure to pay their troops, he suggests.

Wang initiated the Global History of Health Project – Asia Module in 2018, an international collaborative effort that seeks to learn more about ancient humans and how their health varied through different environmental and social changes. The organization is examining skeletal collections from a variety of countries, including China, Mongolia, Russia and India.

Wang has been noted for several other archaeological discoveries, including the earliest confirmed examples of intentional head modification (elongated skulls) dating back 13,000 years, and a 1,500-year-old joint burial with two skeletons locked in embrace. His current research is funded by two National Science Foundation grants.

This article by Caleb Vierkant originally appeared on Dentistry Insider.