Texas A&M Study: White Police Officers Use Force More Often Than Non-White Colleagues

White police officers are far more likely to use force than their nonwhite counterparts, especially in minority neighborhoods, according to a study from Texas A&M University researchers.

The outcome is dramatically different when a white officer responds to a call versus a Black officer in an otherwise similar call, they found. White officers use force 60 percent more often, on average, than Black officers, and fire their guns twice as often, said Texas A&M Professor of Economics Mark Hoekstra.

He and doctoral student CarlyWill Sloan detailed their findings in a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. While white and Black officers discharge their guns at similar rates in white and racially-mixed neighborhoods, white officers are five times as likely to fire a gun in predominantly Black neighborhoods, according to the study.

As an economist, Hoekstra said he’s interested in fairness and equity concerns, as well as efficiency. The results of the study indicate issues with policing in each of those elements, he said.

“The main question we were trying to answer with the project is, is there a race problem when it comes to use of force? Many people clearly believe that race matters,” he said. “On the other hand, others think these incidents are rare, or that some cops use too much force but without regard for race. In addition, most prior research has concluded race isn’t much of a factor. We found clear evidence that race matters, and clear evidence of a race problem.”

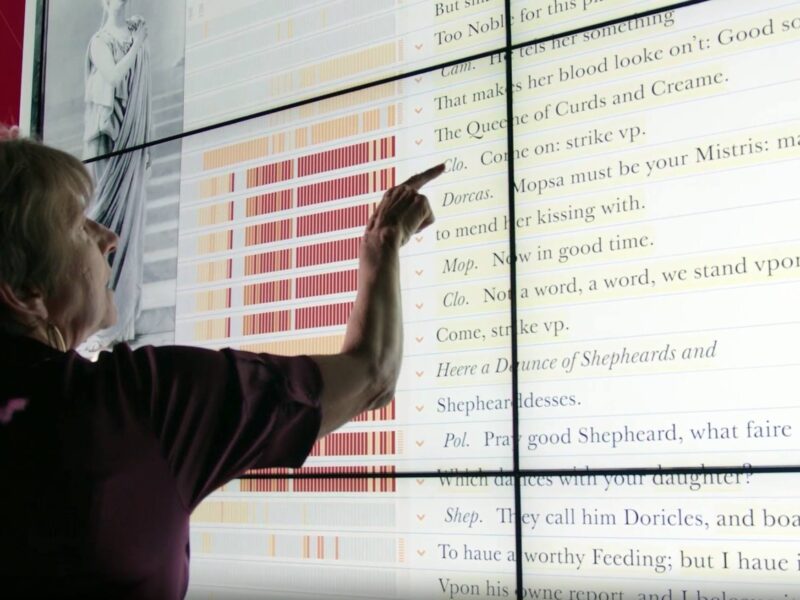

Rather than studying cases where police initiate interactions with the public, or only observing interactions that ended in force and making assumptions about the unobserved interactions, the Texas A&M researchers used a method that differs from previous studies. They obtained data from two major U.S. cities, which are not named in the study, and combed through more than two million calls to 911 emergency lines recorded by dispatchers that contain detailed call addresses, descriptions and priority levels given by the operators.

Hoekstra said they matched this to more than three years of corresponding information about the responding officers’ race, gender and time spent with the department, as well as the type of force used. He said force can include an officer grabbing, punching or kicking an individual — the most common type observed in the data — using a baton, or firing a gun.

To determine the racial makeup of a neighborhood, Hoekstra and Sloan used a geographic information system to match the address of the calls to their corresponding Census Block Groups – the smallest geographical unit of data collected by the Census Bureau – then compared it to Census data showing the race of people who lived in the area.

Hoekstra and Sloan also chose to examine two cities where neither dispatchers nor officers have the discretion to select which officer is assigned to a call. In one city, if the beat officer on duty is unavailable, the closest available officer is then dispatched. The protocol of the other city is to dispatch the closest officer to the call address.

“We picked cities where it would be a clean experiment because of how dispatch protocol works, and where we could get the data,” he said. “For a call in a given location, it’s essentially a coin flip whether a Black or white officer is dispatched.”

While samples they examined do not represent the entire country, they are large enough to draw the conclusion that “race matters, and it matters a lot,” Hoekstra said. “We would also love to replicate this analysis in other cities, and would be happy to work with mayors and police departments to identify if race matters in their city.”

One of the cities has a majority of Hispanic and white residents. Hoekstra said there wasn’t an overall difference in white and Hispanic officers in their likelihood to use force. However, even there, officers were twice as likely to use force in different-race neighborhoods.

But what he called the “most striking” result is that white officers are five times as likely to fire their weapons in predominantly-Black neighborhoods than their Black colleagues. That’s true even though both groups of officers use force similarly in white neighborhoods, suggesting it is not just that white officers are more aggressive everywhere.

“If race doesn’t matter, white and Black cops would scale up use of force similarly,” he said.

Hoekstra said the findings prompt several questions, including whether racial bias drives use of force or if white officers are less skilled at de-escalating or reading situations with Black civilians than Black officers. The research also doesn’t observe the civilian response.

“If Black civilians are more aggressive when a white officer responds, it could explain some of the effect. But if Black civilians are more cooperative with white officers — perhaps out of fear — the effects could be even larger than we observe. I don’t think either response would be surprising, though it’s nearly impossible to distinguish those from the officer’s behavior,” he said.

Hoekstra said the study demonstrates that race matters, even in a time and context during which police departments generally, and white officers in particular, know they are under close scrutiny by media and the public.

The death of Black civilians due to police brutality has prompted widespread unrest across the country after the death of George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis who died after a white police officer pinned his neck with his knee for almost eight minutes. Demonstrations and protests in many U.S. cities have subsequently focused on racial justice and police brutality.

The research has implications for the efficiency of policing, Hoekstra said. And if civilians don’t trust police, “it’s really hard for police to protect civilians and combat crime.”

There are widespread concerns regarding how police officers treat minorities, Hoekstra and Sloan note in the study, “rooted in a long history of police mistreatment of Black Americans.”

“This is reflected both by recent protests over police shootings of unarmed Black males and by the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement,” they write.

Media contacts:

- Kelly Brown, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing & Communications, kelly.brown@tamu.edu

- Mark Hoekstra, markhoekstra@tamu.edu