Preparing For The Next Pandemic

While progress is being made in preparedness efforts against emerging infectious diseases, the United States and the international community remain dangerously vulnerable, according to two Texas A&M University experts.

Dr. Gerald Parker, director of the Pandemic and Biosecurity Policy Program at the Bush School of Government and Public Service, spent more than 30 years in “the eye of the storm” preparing for global disease threats as a former top career official in the Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Defense and the U.S. Army.

“We don’t know what the next threat will be, we don’t know when the threat will come, but when it does arrive, the risks could be high,” Parker said. “Pandemic preparedness is an extremely hard challenge, and response requires coordinated, multidisciplinary action. Emerging infectious diseases are not just the domain of public health. Infectious diseases can impact our economic and national security, requiring strong leadership and political will at all levels.”

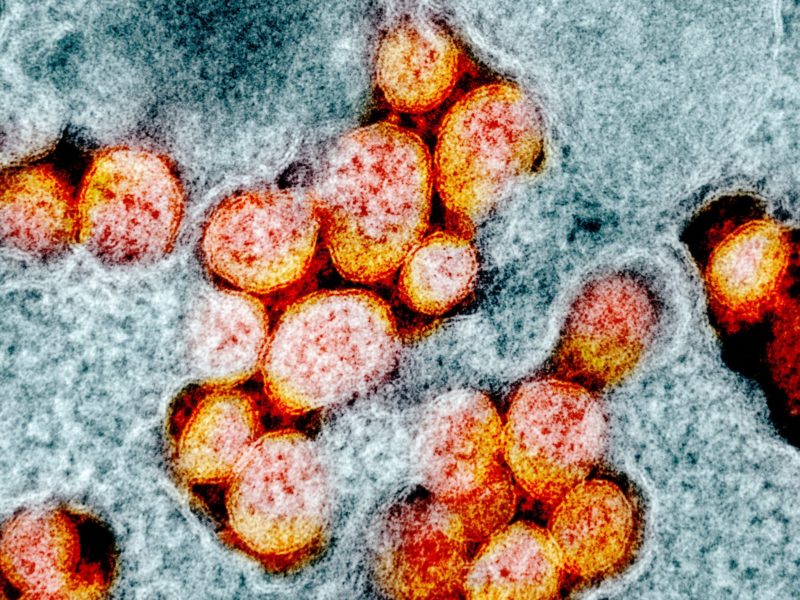

The World Health Organization said last week that China’s coronavirus outbreak should be viewed as “public enemy number one,” and poses a “very grave threat for the rest of the world.” The virus also has a new name – COVID-19, for coronavirus disease 2019. Worldwide there are more than 73,000 confirmed cases in 26 countries, and the death toll has reached 2,000. But to date, the vast majority of cases and deaths have occurred around the epicenter of the outbreak in Wuhan, China.

“Actual numbers are likely higher than reported, and we may be on the verge of a global pandemic of uncertain severity,” Parker said. “There are still many unanswered questions, to include transmissibility, severity, case fatality rate and the origin of the virus. The situation and our understanding of COVID-19 will continue to evolve dynamically.”

As a nation, Parker said, much has been accomplished since anthrax letter attacks in 2001 and a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, including establishing new organizations such as the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority within the Department of Health and Human Services. The U.S. also created federal grant programs to help ready state and local public health authorities and hospitals.

To better prepare for pandemics, Parker said the United States needs the commitment of professionals at the highest levels of the U.S. government focused on emerging infectious diseases and global health security.

“Leadership, coordination, collaboration, communication, and innovation are recurring weaknesses identified by our pandemic and biosecurity policy research at the Bush School,” Parker said. “The U.S. should establish a senior-level position within the White House to lead preparedness and response efforts. Senior leadership with authority is needed to drive coordination, collaboration and effective use of resources in the event of a pandemic. There needs to be someone that can make the hard decisions and effect action across the vast U.S. government interagency.”

The Trump administration released a new national strategy for biodefense in September 2018. Parker said he welcomed the new strategy, but was skeptical of the its approach to vest leadership at the Department of Health and Human Services rather than in the White House. But he said as the COVID-19 outbreak emerged, the administration took decisive action and quickly created a task force, declared a public health emergency and implemented aggressive containment strategies that included a federal quarantine and travel bans from China. The last time a federal quarantine was imposed was over 50 years ago to combat smallpox,” Parker said.

“I would say despite my skepticism before this outbreak, so far the question of leadership has been addressed well,” Parker said. “The administration is taking aggressive actions to keep us safe. And to date, although this is a crisis in China, we only have 15 confirmed cases in the United States.”

We should expect to see more cases in the U.S., Parker said, but actions to date have slowed the spread of the virus, hopefully meaning that local public health officials and hospitals will not be overwhelmed.

Christine Blackburn, the deputy director of the Pandemic & Biosecurity Policy Program at the Bush School, is conducting research on various aspects of pandemic disease policy and control. While COVID-19 is genetically similar to SARS – the epidemic in 2003 also began in China – Blackburn said it’s much more contagious. Watching the current outbreak unfold, Blackburn said China has been significantly more transparent than it was during the SARS outbreak nearly two decades ago.

“When the first cases of SARS emerged, the Chinese government actively suppressed the information, even after it spread internationally,” Blackburn said. “The Chinese government lied about the numbers, and held press conferences where they told numbers they knew to be untrue. That was one of the biggest differences [with the current outbreak], where I noticed that they had at least admitted there was an outbreak and taken steps to contain it.”

Parker added that while there’s still debate about China’s transparency in the latest instance, “there’s no doubt” there’s been an improvement. Still, he said, Chinese scientists and physicians on the front lines of the public health response have likely been stifled by the Chinese government.

“There’s a growing uproar, and I think it’s egregious what happened to the physician in China,” Parker said, referring to the death of Dr. Li Wenliang, who tried to warn about the growing threat of the outbreak. “It’s always an astute physician who notices unusual cases, and so when Dr. Wenliang began to communicate his concerns with colleagues about unusual pneumonia in Wuhan, he was detained and forced to sign a statement that he made false accusations. Tragically, Dr. Wenliang died from COVID-19 bravely caring for his patients.”

Parker also pointed out that while the United States offered over a month ago to send a team of scientists to China to assist and learn more of the dynamics of the virus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has still not been invited.

The most important analysis now is to close scientific knowledge gaps to better guide the response, Parker said. The United States’ containment strategy is working so far, he said, and while there’s heightened alert globally, the local risk currently remains low currently.

But that could change, Parker said, adding that this should serve as an opportunity for the public to become more educated about emerging infectious diseases and to listen for the latest public health guidance. Authorities are using this time to sharpen readiness should containment fail.

“If we were to rewind the clock 100 years to the early 1900s, life expectancy was much lower in some part due to infectious diseases, and our ancestors knew about the risks of infectious diseases,” Parker said. “Many of those threats today are vaccine-preventable, and together with basic hygiene and sanitation the risk of infectious diseases is greatly reduced. Infectious diseases are reemerging and the public and our political leaders have forgotten lessons learned over a century ago.”

The prevailing analysis is that COVID-19 is related to coronaviruses isolated from bats in China, Parker said, but how it made the jump to humans is still an active investigation that will take time. Emerging infectious diseases are increasing with alarming frequency as humans and animals are living closer together in urban settings, he said.

Texas A&M’s Global One Health approach is the confluence of animal, human and environmental sciences.

“The focused application of One Health is essential to prevent, detect and respond to emerging infectious disease, most of which are zoonotic,” Parker said.

Media contact: Caitlin Clark, 979-458-8412, caitlinclark@tamu.edu.