Texas A&M Vet Med Researcher Keeps Human, Animal Lives Safe Through Kissing Bugs Project

Stumbling across an unidentified large black bug in your house may make you feel panicked or even curious. Should you smash it with a nearby shoe? Or scoop it up in a cup and release it outside?

If that insect happens to be a kissing bug, you have another option—send it to Sarah Hamer and her research team at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM).

Kissing bugs—also known as cone-nose bugs, or triatomine insects—feed on human and animal blood. The insects are of particular interest to Hamer because of their potential to transmit the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes Chagas disease, a malady that can lead to acute or chronic heart disease or death in humans, pets, and wildlife. Acute heart disease is severe and has a sudden onset, while chronic heart disease develops over a long period of time.

There is a significant human health burden of Chagas disease in Central and South America and Mexico, where medical doctors are generally aware of the risk of disease. There is far less awareness for the disease in the U.S., despite estimates of over 300,000 infected people in the country.

While many of these individuals are likely to have contracted the disease in Latin America before moving to the U.S., there is increasing recognition for locally acquired human infections in the southern states, where infected kissing bugs are widespread. A growing number of dogs across the South are recognized to be infected, possibly from consuming infected bugs in the environment. While some infected dogs may live happy, health lives, others may die acutely or suffer chronic cardiac disease. Because there is no vaccine and treatment options are limited, efforts to control the vectors and parasite in nature may hold the key for disease prevention.

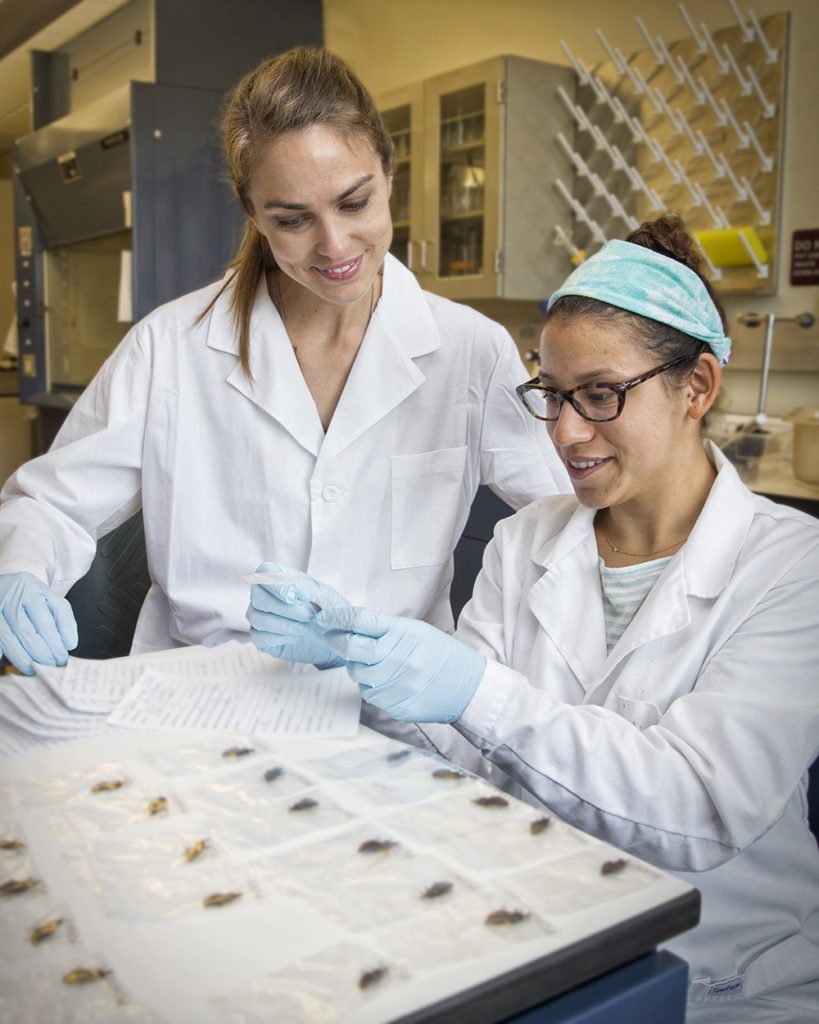

To better understand the risk of Chagas disease in the southern United States, Hamer and her team are taking an ecological approach to characterize the transmission cycles so that the parasite can be managed in nature before it spills over to humans and dogs. They are gauging infection and cardiac health status in pet dogs, working dogs, and shelter dogs across the state. And they are trapping kissing bugs to learn about their infection and feeding patterns across different regions.

When Hamer and her team started researching Chagas disease, they decided it was best to collect bugs from across Texas to address different research questions about the bug’s ecology. However, setting traps for the bugs was inefficient and did not provide enough for research; Hamer said her team often came up empty handed or had few bugs to work with from the field.

After talking to land owners, Hamer realized that many people are familiar with the kissing bug and have seen them on their property.

“People started hanging on to some of these bugs that they would see in their houses or in their dog kennels,” Hamer said. “They would put them in an old pill container or plastic bag and save them for us, and the next time we were out doing field work, we’d look at them.”

As the project grew to emphasize citizen science, the team’s research power expanded; citizen involvement granted the team access to more samples than they could ever dream of collecting themselves.

“We now have well over 3,000 bugs in our collection, which is bigger than any other collection of kissing bugs in the United States,” Hamer said. “Our students still are out actively trapping bugs, but we can’t match the effort of the citizen scientists. It’s huge, and it’s awesome.”

With so much citizen involvement, the program evolved to include outreach materials, such as a website with an interactive map to show where kissing bugs have been collected, informational pamphlets, and an established email account to answer questions and further include the public on the project. Hamer sees the outreach component as a way to educate the public about kissing bugs and protect the public’s health, as well as the health of pets and surrounding wildlife.

While citizen scientists are often interested in knowing whether the bug they submitted is infected, Hamer says the result of any single bug is less informative than the overall epidemiology of the vectors. Finding an infected bug in the yard does not mean the family members or the family dog are at immediate risk for the disease but broadly suggests the region around the home is suitable for kissing bugs and Chagas disease, Hamer said. The team often educates the public specifically about how the disease is transmitted to help the public make decisions about their health.

In fact, Hamer said the route of transmission for Chagas disease can be rather inefficient—the cycle of the disease begins when a kissing bug feeds on the blood of an infected host. But unlike mosquitoes or ticks, kissing bugs cannot spread the parasite by simply biting another animal or person. Instead, the parasite occurs in the bug’s feces, and, therefore, the bug must defecate on a person or animal and the infected fecal material must be absorbed into the skin through the eyes, mouth, or a wound created by the kissing bug biting the victim. That series of events can be a rare occurrence, especially given a good standard of housing where bugs are unlikely to colonize inside the homes to reach people. However, oral transmission can also occur, and Hamer said dogs can contract the disease by consuming an infected kissing bug.

Once inside the new host, the parasite circulates in the blood for some time and then can infect different organs, including the heart, where it replicates, causing damage to the heart tissue cells. Over time, more and more heart tissue cells are destroyed, which can lead to heart disease.

While the effects of Chagas can be fatal, many infected individuals may never know they have been infected. It’s not possible to predict which infected individuals will suffer disease, and so physicians and veterinarians have a difficult time discussing the prognosis. Hamer said some people infected with Chagas may find out after donating blood, since blood banks now routinely screen for Chagas antibodies.

Because there is no cure for Chagas disease, only treatments to manage the symptoms, Hamer emphasizes that studying the parasite in bugs and wildlife can provide key data to protect the health of humans and dogs, and public outreach is a key component.

“We are working on a cell phone app as a future direction to enhance our outreach and research,” Hamer said. “People can upload pictures of their bugs and the app will time stamp it and mark it with location data. In addition, the app will also be a simple interface to get good information about kissing bugs and Chagas disease.”

The team is collaborating with other veterinarians, parasitologists, entomologists, geographers, diagnosticians, and public health officials at Texas A&M, the state health department, other universities—including in Mexico and Brazil—and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Without collaboration and teamwork, Hamer’s research interests and efforts to educate the public about Chagas would not be possible.

To learn more and submitting a kissing bug to the TAMU Citizen Science Kissing Bug program visit kissingbug.tamu.edu.

###

This story originally appeared on the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences website.