Educational neuroscience is an emerging field that Dr. Steven Woltering wants to be on the leading edge of. His latest research on self-regulation will play a key role with implications across education from parents and educators to school psychologists and clinicians.

Self-regulation is defined as the ability to manage thoughts and emotions and to flexibly adjust internal goals and responses to the changing demands of a situation. It is increasingly recognized as a key predictor of academic and social competence.

“We found out that out of the demographic information, self-regulation is the only significant, consistent predictor over the developmental span for predicting future problematic behaviors. That means, if you have a child who is confident, flexible, emotionally stable and persistent, they will be less likely to have problems in the future,” explained Qinxin Shi.

Shi, a doctoral student in Educational Psychology, collaborated with Woltering, assistant professor of learning sciences, on the latest research and sees potential in both the education and neuroscience fields.

“Much of the demographic information is hard to change as an educator. However, we can put in efforts into self-regulation and we can help the child to be flexible and be persistent. We see this as potential to help kids improve self-regulation at a very early age,” added Shi.

https://today.tamu.edu/2016/12/08/what-is-shadow-education/

Woltering has long had a passion for research self-regulation, his interest stemming from his time as an elementary school teacher. He noticed that some students could be corrected once and not repeat the mistake while others kept testing the limits and would have difficulty following the rules.

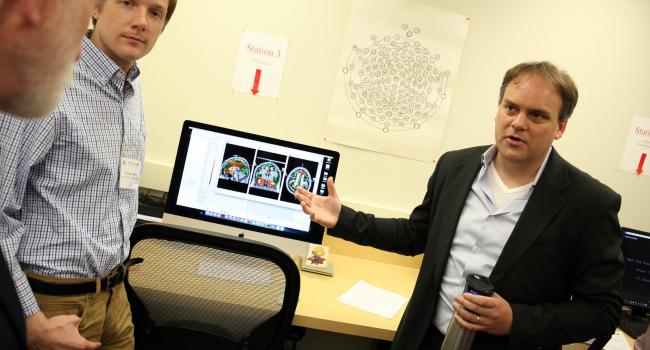

“We wanted to see if there were particular neural correlates we could find – markers in the brain – that would be consistent and show individual differences between kids who have problem behaviors and kids who don’t.”

For these studies, Woltering and Shi focused on the anterior cingulate cortex, or ACC, activation. It is located centrally in the brain and viewed as central in a network supporting the flexible regulation of behavior.

In the research, they found a set of (EEG) indices that relate to individual differences in self-regulation. They also found at a neural level, findings are similar to the developmental trajectory of self-regulation reported at a behavioral level. Patterns for both typically show continued improvement of self-regulation from early to middle childhood and stabilizing by early adolescence.

A second goal of this research was to determine if those neural indices changed with successful treatment.

“We wanted to see whether those neural patterns would normalize if we were to have these kids go through a treatment that would target their self-regulation ability, make them more calm and flexible in dealing with other kids,” explained Dr. Woltering.

Research showed that yes, there were changes in ACC activation with successful treatment. Those findings are promising for clinicians and educators in addressing children with disruptive behavior disorders.

Dr. Woltering made it clear that, for these children with disruptive behavior problems, aggression and defiance are a means of feeling in control and asserting themselves.

“For those kids who need it the most – it’s not that you have to punish them and put them in the corner, that’s actually the worst thing to do for those specific kids. The punishment can become counterproductive and you need to offer them an alternative – a simpler way in which they can handle and have control over their own emotions and their ability to self-regulate their own emotions in different situations,” added Dr. Woltering.

Research found that corrective measures used in schools now are effective for most children but not all. Some students still show aggression and are often diagnosed with disruptive behavior problems. Those diagnoses constitute half of the referrals to children’s mental health agencies.

“I don’t want to dismiss those techniques because they’ve very helpful. But, for a certain subset of kids with disruptive behavior problems, we need to think flexibly ourselves to determine how we can best help them,” said Dr. Woltering. “We need to spend more money and time and research not just looking at these symptoms, but looking at those therapies and those intervention techniques that can bolster self-regulation, social skills and flexibility training.”

Research on the neural markers related to self-regulation is in its infancy, but Woltering believes the latest findings have the potential to have implications for better identification, prevention and treatment related to self-regulation in schools that could lead to better learning outcomes.

“I look forward to an ongoing discussion on this topic in the future. Hopefully we can contribute more into this area of trying to bridge education and neuroscience a bit more. It’s a tough journey and it’s not going to be easy, but I think this is a good first step.”

###

This story by Ashley Green was originally posted on Transform Lives.