Soil Bacteria May Improve Understanding Of Antibiotic Resistance

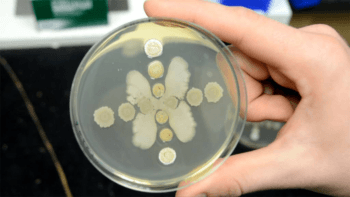

Two types of bacteria found in the soil have enabled scientists at Texas A&M AgriLife Research to get the dirt on how resistance to antibiotics develops along with a separate survival strategy.

The study, published in the journal PLoS Genetics this month, identifies an atypical antibiotic molecule and the way in which the resistance to that molecule arises, including the identity of the genes that are responsible, according to Dr. Paul Straight, AgriLife Research biochemist.

Straight and his doctoral student Reed Stubbendieck observed a species of bacteria changing its appearance and moving away from a drug to avoid being killed.

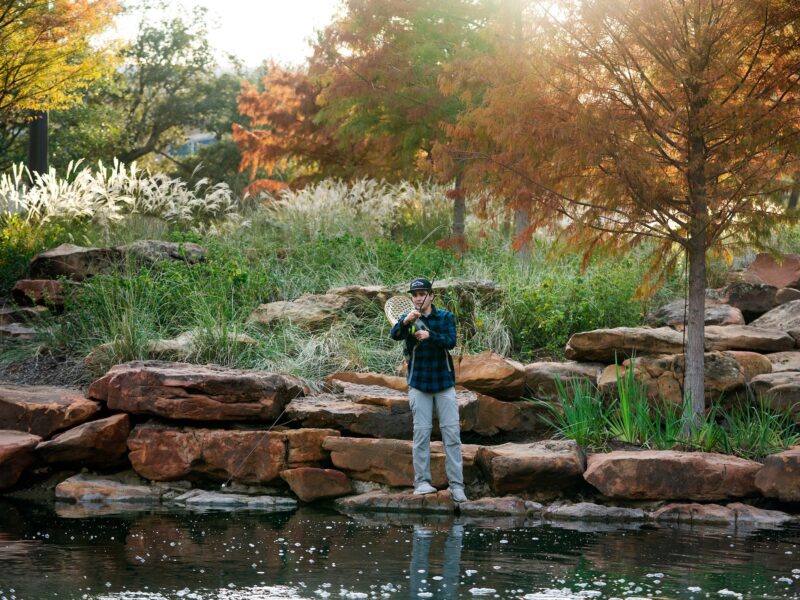

Straight’s lab on the Texas A&M University campus in College Station in general focuses on understanding how communities of bacteria interact with each other and other microbes.

“Over the past few decades, scientists have come to understand that bacteria aren’t just single individual cells that somehow cause infections or degrade toxins, for example,” Straight said. “In fact, they are populations and communities of many, many cells, whether just a single species of bacteria or a very diverse community. We are most recently aware of this in terms of the human microbiome. People have more bacteria cells in them than they have human cells.”

But what has not been fully understood about bacteria and microbes in general, he said, is the way in which they form these types of communities with more than one species.

“It’s both an ecological and a mechanistic bacteriology question,” Straight said. “For nearly 100 years, we’ve known that bacteria can produce molecules that can block the growth of other organisms including other bacteria, and those molecules have been very useful as antibiotics.”

Straight said the common understanding of the usefulness of antibiotics, however, sidestepped the ecological dynamics of the bacteria themselves in how they form communities, and interact with each other.

“We wanted to know what happens when we put two bacterial species together to compete with each other and use that model as a way to identify new molecules, identify pathways, or gene functions, that are required for the bacteria to survive under competitive stress,” he explained. “Identification of interesting new molecules or bacterial mechanisms of control that one might exploit can lead to developing a new antibiotic.”

Continue reading on AgriLife Today.

This article by Kathleen Phillips originally appeared in AgriLife Today.