James Earl Rudder: The D-Day Hero Who Led Texas A&M Into A New Era

Seventy-nine years ago, the world was at war. As Allied forces launched a campaign to liberate France from Nazi occupation, some 150,000 troops landed on the beaches at Normandy the morning of June 6, 1944.

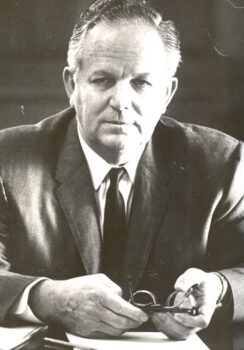

Among them was future Texas A&M University President James Earl Rudder, a lieutenant colonel at the time, who led his group of Army Rangers up the steep cliffs at Pointe du Hoc to capture a Germany artillery position. This assault solidified Rudder as a hero of the D-Day landings and the war at large, setting the stage for the rest of his life.

To mark the anniversary of D-Day and the birth of Rudder’s enduring legacy, Texas A&M Today spoke with Dr. Thomas M. Hatfield, director and senior research fellow at the Briscoe Center for American History and author of “Rudder: From Leader to Legend.” As Hatfield explains, there’s a lot more to the story of this legendary soldier-turned-educator.

How did the story of Rudder and his Rangers capturing Pointe du Hoc become so legendary, and why do you think it continues to resonate today?

The successful assault up the 100-foot cliffs of Pointe du Hoc by Rudder’s 2nd Rangers has become enshrined in legend. The scene looking down the cliffs, over the narrow beach below and out to sea captures the imagination, leaving an image that is forever memorable. The captivating scene is one of the great photo-ops of the world. That’s why several of our presidents have gone there, notably Ronald Reagan for the 40th anniversary of D-Day when he talked about “the boys of Pointe du Hoc” — touching words that still resonate around the world. The widowed Mrs. Rudder sat beside Nancy Reagan during the president’s famous speech.

What happened at Pointe du Hoc is a significant event in U.S. Army history and is related to the motto, “Rangers, Lead the Way.” In comparison to countless acts of heroism by American soldiers on D-Day, the valiant actions by those Rangers stand above all the others by the mere fact that they were so daring and conspicuous. Ten years later, when Rudder went back the first time, he wondered aloud almost to himself, “How did we do this? It was crazy then and it’s crazy now.” Civilians visiting Pointe du Hoc stand in awe while professional soldiers study it as a metaphor for special operation — a precarious attack by a group of highly trained soldiers intent on destroying an enemy target for the sake of achieving a larger goal: the landing on Omaha Beach. After Pointe du Hoc, Rudder would never have to explain himself to anyone, least of all to himself. He had proven himself good all the way through, mentally and physically.

You’ve made regular visits to Pointe du Hoc for many years now. What stands out to you when you see that place in person?

For the casual visitor at Pointe du Hoc, the bomb craters and the dramatic views of the sea create the strongest impressions. I encourage my companions to contemplate the qualities, both physical and mental, that were required by Rudder’s lightly armed Rangers to overcome their entrenched and well-equipped enemy. They were extraordinarily brave and daring, but less obvious qualities were required — devotion, courage, intellect, boldness, determination, perseverance and willingness to die for each other and a cause. These are qualities that Prussian General and military philosopher Carl von Clausewitz calls “the moral factors,” which Rudder, as their leader, demonstrated in spades.

When I go there I think about the planning and preparation, and the crises he overcame just to get his men to the Pointe. In the final hours he faced down two major crises that could have defeated him and the entire effort — the drunkenness of a key subordinate and a British naval officer’s navigational error approaching from the sea — but he was calmly resolute and overcame both of them, turning adversity into triumph which was his special talent. I also think of Rudder’s devotion to the men who served under him, leading them from the front, and never seeking a safe place while others were exposed. To the end of their days they talked about how accessible he was, and cared for them as though they were his younger brothers, unless they disappointed him.

How did Rudder’s military service and his reputation as a war hero help shape his postwar career as a leader in government and higher education?

Rudder returned from the war believing as he wrote, “I was saved for a purpose.” As before, people gravitated to him and now even more so. He was a highly decorated war hero who had served in perilous places. He returned with his magnetic personality more freely expressed, the same million-dollar smile, was warmly engaging with his fellow citizens, seeing value in every person. He was little known beyond Eden, Texas, his birthplace, and Brady, his adopted hometown of some 5,000 where only four months after returning he was elected mayor by popular demand, and subsequently for two more two-year terms. Even his former opponent voted for him. Outwardly, he was the same person, but inwardly his values were those of a reflective, selfless servant leader, the committed public servant he would be for the rest of his life.

His decision not to return to his pre-war job as Tarleton State’s head football coach forecast a new vector in his aspirations. Late in the war, he had written to his wife about devoting their lives to “taking care of the children” — the children of America — and making the world a better place where there would be no more wars.

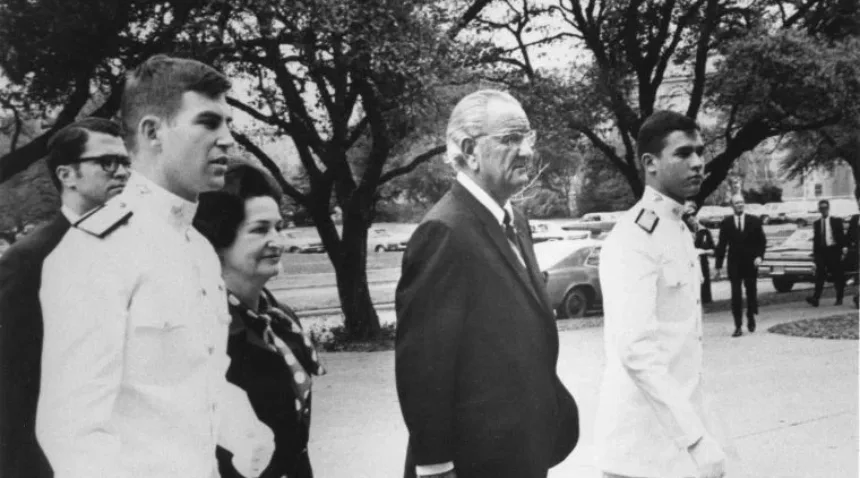

As a proven vote-getter, ambitious politicians like Congressman Lyndon Johnson, John Connally, a future Texas governor, and Alan Shivers, a dominant political figure in the state and governor from 1949 to 1957, wanted Rudder on their team. They sought his endorsement and cultivated him, appointing him to state and federal commissions, where he served dutifully. Shivers finally drew him out of Brady by appointing him commissioner of the General Land Office in 1955, normally a statewide elected office. When his appointed term expired the next year, Rudder filed for election, campaigned in almost every county, and was elected to the office in his own right, which was a factor in his move to Texas A&M in 1958.

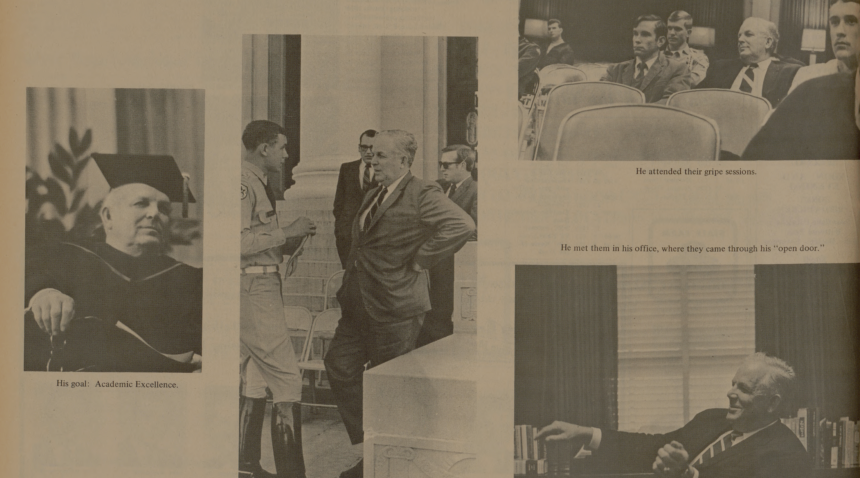

At A&M, Rudder is most well-known for overseeing a time of great change. How did he navigate the shifting social and political currents of his time, and what lessons can we draw from his leadership during that period?

As on the battlefield, moral courage is important to leadership in higher education, politics and business, or any other type of organization. From the first day he sat down at his desk at Texas A&M, he had to deal with the fact that the mostly “all-male, all-military” land-grant college was falling behind rising universities across the state, obviously in enrollment trends. Change is always difficult and some of A&M’s most prominent alumni were opposed to practically any change, but Rudder followed the facts as he found them, remarking to his wife, “If A&M does not change, it will become less important than the smallest junior college.”

He commissioned studies that supported his position and made long-range plans that forecast a bright future for Texas A&M, a “sleeping giant,” he believed. Gradually, A&M’s most important decision-makers — its Board of Regents — realized that he was acting in the long-term best interests of Texas A&M. Once committed, he did not waver and people followed him, demonstrating once again that personal courage is contagious. He defined courage as “the ability to do what’s right regardless of what’s happening.”

Media contact: Luke Henkhaus, henkhaus@tamu.edu