Down The Drain: Pharmaceuticals And Personal Care Products In The Water

We rely on a of variety substances, from antibiotics and aspirin to shampoo and sunscreen, to make modern life more comfortable and convenient. But these pharmaceuticals and personal care products, commonly called PPCPs, have lives that go on long after we use them. They enter our wastewater when they get washed down the drain or flushed down the toilet after passing through our bodies. After that, they end up in the environment. But what does that mean for ecosystems and human health?

To answer that question, Texas A&M School of Public Health researchers first looked at previous studies on PPCPs and how they affect the environment, publishing a review article of their findings in the journal Environmental Chemical Letters. Antibiotics are an important subset of PPCPs, and the World Health Organization has identified antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes as the major health issue of the century. Therefore, the research team also examined previous studies relating to treatment strategies for antibiotic resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes and published this review in Chemosphere.

The purpose of the first review was to establish what is already known about PPCPs. “We pulled together all of the research to give a starting point,” said Leslie Cizmas, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health at the Texas A&M School of Public Health and first author of the paper. “We tried to see what we need to learn and how to prioritize which compounds to look at.”

Much of the current concern about PPCPs is how they persist and affect the environment and the various species in it. Research on the effects of PPCPs in algae has been important in these efforts because algae are sensitive and can be tested quickly. Researchers also looked at studies of fish and other organisms at the other end of the size spectrum from algae. “We need to understand what’s going on at each trophic level,” said Cizmas. “Bioaccumulation, or the intake and concentration of chemicals in organisms, and biomagnification, in which chemicals are passed up the food chain and become more concentrated in higher predators, are also problems that need to be considered.”

In addition to these ecological concerns, there are potential human health issues related to PPCPs on the horizon. Population growth and increased reliance on water reuse, especially in drought-prone areas, could increase PPCP concentrations to a level where they start affecting humans as well. A specific side effect, higher levels of antibiotics in wastewater, could promote the spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria. “Further research will be needed to clarify this issue and point to antibiotics that should be saved for last line human use,” Cizmas said.

A major reason why PPCPs accumulate is that once they go down the drain, these substances tend to stick around. When they mix with other substances, even larger problems can develop because some PPCPs can affect the toxicity of other PPCPs, making a mixture that is more toxic than either would be on their own.

“Wastewater treatment plants aren’t really designed to take these things out of the water,” Cizmas said. “PPCPs can pass through these facilities into the environment largely untouched, and in some cases, these compounds can react with disinfecting agents like chlorine to produce new substances that could be harmful.”

The exact toxicity mechanisms after release of PPCPs from wastewater treatment plants is still largely unknown, Cizmas and her colleagues found, so they plan to study that subject next. This work is also looking at new methods that could remove PPCPs from wastewater. To be effective, removal methods will need to get rid of at least the most toxic and persistent compounds and be relatively inexpensive. Maintaining and upgrading wastewater infrastructure takes large amounts of money that many localities simply don’t have. “We need further research into cost-effective treatment methods, which is something we continue to look into,” said Cizmas.

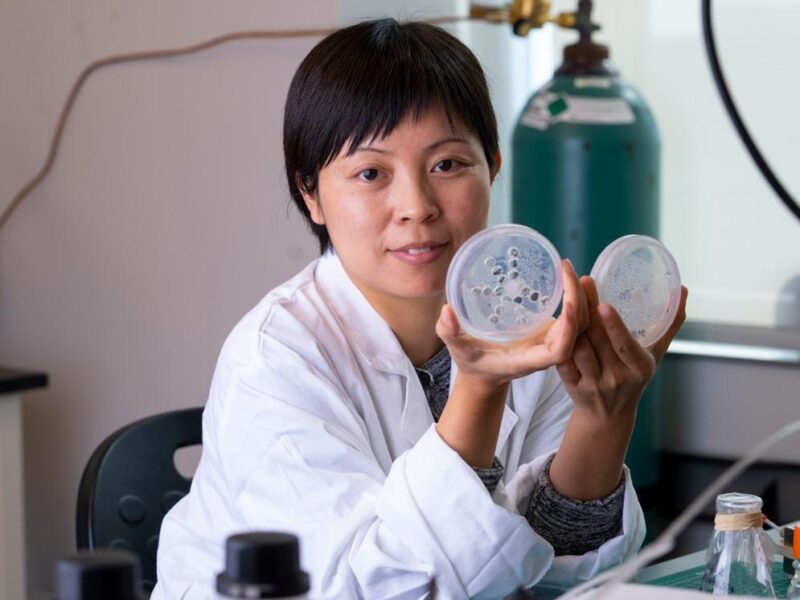

The international interest in this research has brought several researchers from around the globe to the Texas A&M School of Public Health.

“Water pollution is a problem in Europe,” said Pavla Plachtova, a Fulbright Scholar from the Czech Republic currently studying the toxicity of various mixtures of pharmaceuticals to algae at the school.

“Cizmas’ approach of using an iron-based disinfectant (i.e., ferrate) will reduce this toxicity,” according to Virender Sharma, PhD, MTech, MSc, professor at the School of Public health and a pioneer in ferrate research.

Additional research will depend on prioritizing which PPCPs to focus on. Antibiotics are a particular concern because of emerging worldwide antibiotic resistant bacteria. Not all PPCPs are created equal, so researchers need to pay special attention to compound concentrations, toxicity and persistence, and how they interact with each other. This, in turn, will help policy makers decide where to focus their efforts, whether it’s upgraded wastewater infrastructure, or restrictions on how these substances are used.

These and other studies coming from the questions clarified by the initial review articles aim to better understand the complicated mixtures of PPCPs that are currently in our waterways, and seek to find ways to minimize any harm caused by these useful compounds. “Water scarcity is predicted to be a major problem in the next century. Water reuse is likely to become more common, and we need to develop sustainable methods for managing our water resources,” said Cizmas.

This story originally appeared on Vital Record.

This story originally appeared on Vital Record.