Texas A&M Lab Searching For A Global Solution To Locust Outbreaks

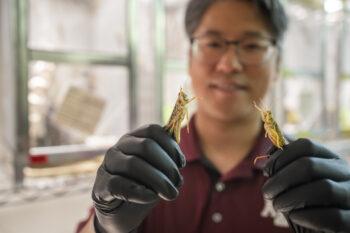

The Behavioral Plasticity Research Institute at Texas A&M is researching an insect that has plagued humans for thousands of years – locusts.

For the first time, researchers across Texas A&M AgriLife can now import and study many major global pests by utilizing the U.S. Department of Agriculture-approved insect quarantine facility maintained by the Department of Entomology at Texas A&M’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Dr. Hojun Song, a professor in the Department of Entomology and one of the lead researchers at the institute, said locust outbreaks impact the livelihoods of one in 10 people on the planet.

The most recent locust outbreak occurred from 2019-2022 and caused more than $1.3 billion in crop damage in 23 countries across eastern Africa, the Middle East and Asia, from Ethiopia to Nepal.

All locusts are grasshoppers, but not all grasshoppers are locusts. There are about 20 known locust species among the 7,000 species of grasshoppers. They are characterized by the ability to transform through a phenomenon called locust phase polyphenism, which changes their biology, morphology, color and behavior.

This transformation is triggered by population density. At low density, they are shy and avoid each other, but at high density, locusts become gregarious and form large collective swarms that migrate.

Song and other researchers at the institute hope to learn more about locust phase polyphenism and what stimulates locusts to change, so that technology might one day mitigate their impact on humans.

“I like to compare the change to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde or Bruce Banner and the Hulk,” he said. “I’ve been fascinated with the transformation and the biology of locusts for years, and this institute has allowed researchers like me to study them.”

The First-Of-Its-Kind Rearing Facility At Texas A&M

The Texas A&M facility is part of a five-year, $12.5 million multi-institution research institute established through the National Science Foundation. It includes researchers from Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Baylor College of Medicine, Arizona State University, Washington University in St. Louis, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville and the USDA-Agricultural Research Service. The locust rearing facility at Texas A&M is one of two facilities that study locusts in the U.S.

The collaborative institute integrates a range of biological disciplines, including evolutionary and molecular sciences, to understand the larger phenomenon, Song said. The research is in its third year.

The multi-institutional, multi-disciplinary effort is led by Song and fellow Texas A&M entomology professor Dr. Spencer Behmer. They are joined by Dr. Fabrizio Gabbiani, professor of neuroscience, and Dr. Herman Dierick, associate professor of molecular and human genetics, both at Baylor, as well as Dr. Arianne Cease, associate professor of sustainability and director of the Global Locust Initiative at Arizona State.

The team with wide-ranging expertise also includes Texas A&M’s Dr. Greg Sword, Regents Professor and Charles R. Parencia Endowed Chair in the Department of Entomology. From the Baylor College of Medicine are Dr. Erez Lieberman Aiden, associate professor; Dr. Chenghang Zong, assistant professor; Dr. Olga Dudchenko, research assistant professor; and Dr. Stephen Richards, project scientist, Earth BioGenome Project. Other team members are Dr. Rick Overson, senior scientist, Arizona State; Dr. Barani Raman, professor, Washington University in St. Louis; Dr. Brittany Peterson, assistant professor, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville; and Dr. Anna Childers, computational biologist, USDA Agricultural Research Services.

The team at Texas A&M studies two species of locusts – one found in North Africa and the Middle East and another found in Central America. The Texas A&M locust lab is the only lab in the world that houses multiple species of closely related locusts and grasshoppers as well as the technology to compare their physiological, behavioral and functional genetic differences.

Sword said the institute brings together resources and expertise in an unprecedented way. The ability to study and understand locusts at a molecular level could present a basis for their management in the future.

“The institute is in an incredible position to impact the field and provide an understanding of locusts at the molecular level, which will be fundamental to their management in the landscape,” he said. “It has completely changed our ability to study locusts, but the work is still in front of us.”

Research Institute Prepares For The Future

Song said locust swarms may not impact the U.S. now, but climate change and future migration patterns of locusts found in Mexico are legitimate concerns. The institute is taking a preemptive approach to understanding the biological and ecological factors that trigger swarms and create technology and plans to mitigate potential devastation.

“The U.S. does not have locusts, so historically there has been minimal funding allocated to study them,” he said. “However, we’ve done modeling to see if the distribution might change over 20 years, 100 years. All models say the Central American locust will come to Southern Texas, so, we are preparing to protect Texas and U.S. croplands.”

Song said much of the global response to major locust infestations has been reactive. The cycle of funding can be politically driven and requires cooperation between neighboring nations where conflict and blame are difficult for scientists to navigate.

“It is good that it is at least an internal concern among leaders here in the U.S. and they had the foresight to say it might be worth investing in research,” he said. “Being proactive rather than reactive is critical, and we’re making good progress.”

Sword said major outbreaks have been rare, but there has been no shortage of outbreaks over the last century to make the case for the research. The political and social will to monitor and control locusts has to be there for consistent research investment.

“Humans have been observing locusts forever, and there are aspects to outbreaks we don’t understand,” he said. “Most of the time, they aren’t swarming, and small populations are difficult to find and monitor in very remote areas. That is why this facility is so critical in our search for understanding polyphenism and what conditions trigger the phenomenon in different species.”

Institute Seeks Scientific Equity And Inclusion

Song said the Behavioral Plasticity Research Institute has two additional objectives beyond understanding polyphenism – training undergraduate and graduate students across the discipline spectrum and creating a pipeline of professionals as part of the Global Locust Initiative at Arizona State University.

There are already several graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and undergraduate students working across the institute, Song said. The institute is also mindful of the need for collaboration with stakeholders and communities and providing science-based knowledge, education and outreach.

The Global Locust Initiative network is a partner of the Behavioral Plasticity Research Institute that hopes to reach out to stakeholders and scientists in impacted nations and residents in those regions, Song said. Extending research opportunities and seeking input from and/or engaging with all partners and stakeholders will be critical to the institute’s ultimate success and sustained impact on locusts plaguing humans.

“Traditionally, locust research has been done by European scientists, and we want this institute to be a vehicle to provide student and research opportunities that adhere to our commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion,” Song said. “It’s a partnership and is not just about Texas A&M and Arizona State University. This lab and institute are part of a global initiative, and having a partnership between scientists and stakeholders demonstrates our commitment to collaboration and providing global solutions.”

This article by Adam Russell originally appeared on AgriLife Today.