What Is Monkeypox? And Should We Be Worried?

Texas health officials reported the state’s first identified case of monkeypox last week in a Dallas County resident who had recently traveled internationally. The rare disease doesn’t currently present a risk to the general public, experts say, but there’s a reason why health officials are closely monitoring its spread.

“When there is something unusual happening epidemiologically, an investigation is almost always warranted. This is exactly what is happening in the world right now,” said Rebecca Fischer, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Texas A&M University.

A few things stand out to epidemiologists that are raising alarms about the reports of monkeypox now confirmed in more than 30 countries, Fischer said. As of June 13, 65 cases had been confirmed across 17 states and in Washington, D.C., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Notably, Fischer said, these infections are being seen in unusual places.

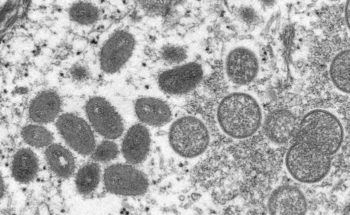

Monkeypox has typically only been seen sporadically outside of West and Central Africa, where the virus is endemic. It’s rarely reported in the U.S., Fischer said, where it doesn’t naturally occur. The sheer number of cases and the sharp increase is also unusual. For a rare disease like this, even one or two cases can constitute an outbreak.

Fischer said it’s also significant that not all countries are reporting isolated cases. Clusters of infections appear to arise from contact with travelers who return home with the infection, indicating an outbreak resulting from person-to-person spread.

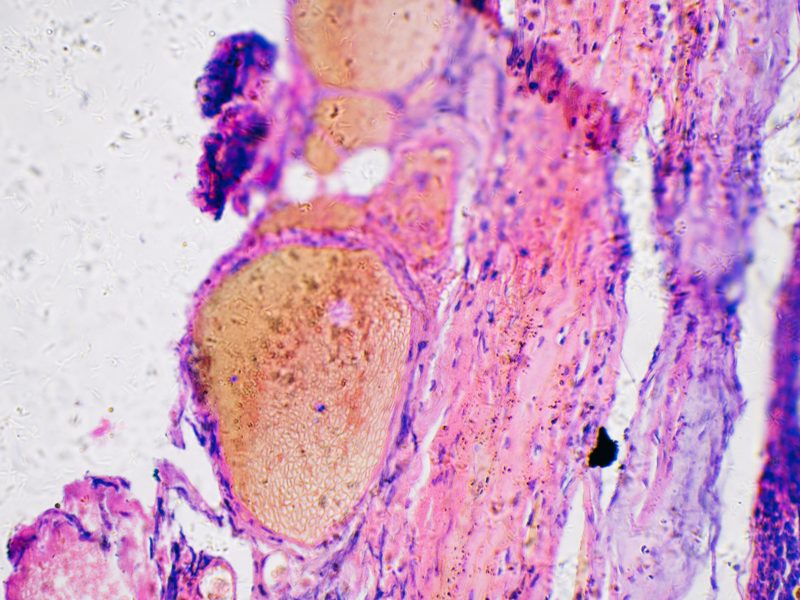

According to the CDC, transmission occurs through direct contact with an infected person’s body fluids, especially through inhalation of respiratory droplets or contact with the skin lesions that are characteristic of monkeypox. Symptoms often begin with fever, headaches, muscle aches and exhaustion.

“The clusters that are appearing need to be quickly investigated for public health officials to pinpoint how, where and why in order to stop that process as quickly as possible,” Fischer said.

Between the person-to-person spread and a mobile modern-day population, there’s no guarantee that the virus will stay where it is or that it has not already spread more widely, Fischer said. It can take up to three weeks for symptoms to appear after a person if infected, “meaning the rest of the story is likely to continue to play out for some time.”

But due to its transmissibility, monkeypox is not likely to be a global health threat on the scale of COVID-19, said School of Public Health Dean Shawn Gibbs.

“However, it is important that healthcare facilities be able to identify it quickly and isolate it appropriately for the protection of healthcare workers and the population,” he said.

Fischer said clusters of infection can be contained through contact tracing, isolation and quarantine protocols. Recent evidence also suggests the clusters are linked to sexual contact, which makes exposure tracking more feasible than with casual community interactions, such as workplace or school environments.

For now, experts say it’s unlikely monkeypox will behave or evolve in the same ways as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Additionally, Fischer added, “we could not be in a better position to have the tools and the public knowledge about what needs to be done.”

There’s no reason to panic or be afraid about the disease at this point, she said, but it’s also important to avoid complacency about monkeypox or any other disease with outbreak potential.

This may be difficult, though, with society at large suffering from pandemic fatigue, said Dr. Gerald Parker, associate dean for the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences.

Parker is also the associate dean for Global One Health at Texas A&M and director of the Bush School’s Pandemic Policy and Biosecurity Policy Program. “Everyone is exhausted,” he said, and that includes public health professionals who will continue to respond to new threats the best they can.

He’s among the experts who have called for a bi-partisan commission to take stock of lessons learned from COVID-19 similar to the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. The commission created following the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks catalyzed legislative and policy changes and resulted in funding for homeland and national security, Parker said.

As of yet, there has been insufficient momentum to establish such a bi-partisan commission on COVID-19, he said, adding that the U.S. was not as prepared as it should have been for a pandemic before SARS-CoV-2 emerged.

“There were some successes with the COVID-19 response like Operation Warp Speed, but also many failures – especially risk communications,” Parker said. “The Biden administration began to propose new pandemic preparedness initiatives as early as September 2021 to prepare for future pandemics.

“Unfortunately, new preparedness initiatives have not been funded by Congress,” he said. “Even ongoing COVID-19 response activities, like second-generation COVID vaccines that may be needed for the fall and winter of 2022, have not been funded yet.”

Like Fischer and Gibbs, Parker said there is no reason to be “overly concerned” about monkeypox based on currently available information. For now, he recommends the public pay attention to public health authorities and trusted voices.

“The CDC has released 1,200 doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine manufactured by Bavarian Nordic and approved for post exposure prophylaxis in people with a high risk exposure to monkeypox,” he said. “Thankfully, our Strategic National Stockpile has 36,000 doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine immediately available, and more doses are being ordered. The stockpile also has 100 million doses of the older ACAM 2000 smallpox vaccine that is effective against monkeypox. There is also an approved antiviral. The vaccines and antiviral were originally developed, manufactured and stockpiled due to the threat of a potential bioterror attack from smallpox, but they are also effective against monkeypox.”

While monkeypox may not have pandemic potential, Parker said it’s the latest example of an era of naturally emerging and remerging infectious disease the world has entered.

“Pandemic preparedness for all biological threats, whether from natural, accidental or deliberate origin, is essential,” he said.

Media contact: Caitlin Clark, caitlinclark@tamu.edu