One Man’s Trash

The great outdoors is rooted deeply in the fibers of Carl McAfee’s being, and has been for his entire life.

Growing up in the backlands of Montana — a picturesque sprawl of untamed rivers and thicketed forests nestled beneath the majestic backdrop of the Northern Rockies — hunting and fishing along with other of nature’s bounties were just a step outside the back door of his family home in Missoula. McAfee still calls it the “best childhood in the world.” He only wishes today’s generation of youth could experience that same idyllic childhood, especially his three young grandsons.

“The only way that’s going to happen is if we fix the global pollution issues that we’ve created,” said McAfee, who earned his Ph.D. in analytical chemistry from Texas A&M University in 1990. “But it can be solved; we have technology that’s effective and useful.”

McAfee would know. For the last decade his company, McAfee Consulting LLC, headquartered in Kennedale, Texas, and specializing in chemical analysis services, has been leading an innovative effort to fabricate composites of recycled rubber and plastic polymers that can be used to construct a variety of materials for governmental and industrial purposes.

According to a 2021 Congressionally mandated report from the National Academy of Sciences, the U.S. ranks as the world’s leading contributor of plastic waste and was responsible for 42 million metric tons of it in 2016 — almost twice as much as China. One possible solution, McAfee says, can be found in a rather uncanny place: landfills, which he describes as the goldmines of the 21st century.

“There are valuable materials in the scrap plastics and garbage dumps,” he said. “We spend so much time and money making them, rather than throw them away, we can use them as a raw material.”

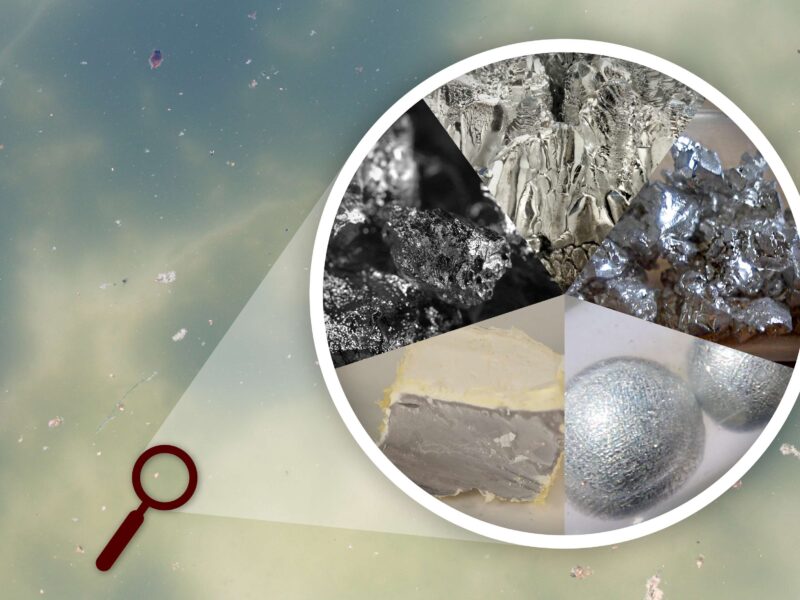

These rubber-plastic composites, which are made by blending different ratios of rubber and plastic to produce an entirely new material with its own unique chemical and physical properties, are rapidly gaining popularity in manufacturing sectors for their durability and overall benefit to the environment. McAfee’s clientele, mostly small-to-medium-sized producers, are using his rubber-plastic composites to design things like pallets and railroad ties to replace those made of wood, floor tiles, tires and modified asphalts for roofing and roadway paving.

He’s currently working on one of his more novel undertakings — polymer-encased rifle cartridges for Garland-based ammunition manufacturer True Velocity. Among their advantages over traditional brass cartridges, the composite variety transfer much less heat to the rifle chamber due to the insulating properties of the polymer case, while their refigured dimensions allow for improved accuracy. They’re also 30% lighter than traditional brass, a detail that has caught the attention of the U.S. military since the reduced weight would lower the costs of shipping them in bulk and enable soldiers to carry additional rounds.

The heart of McAfee’s mission along with his science is his polymer characterization lab. After first meeting with his customer to ascertain their needs and specifications, McAfee utilizes an array of state-of-the-art equipment and analytical techniques to precisely identify the polymer’s chemical composition. Infrared instruments create a chemical fingerprint of a material; thermal analysis is used to determine its melting, molding and crystallization temperatures; and x-ray fluorescence identifies its elemental composition.

By combining his raw material with carefully selected reinforcement polymers, McAfee then executes the art of his science, successfully tailoring the properties of the resulting composite, such as its flexibility or heat resistance, to meet specific requirements.

“Polymers are the new material of the last 20, 30 years — kind of like 100 years ago when it was all about metals and alloys,” McAfee said. “Sustainability is a hot topic right now, and businesses are wanting to do it; that’s why I’m doing my best to teach and educate my clients. The knowledge base is expanding, and the economics are becoming increasingly favorable as more companies are utilizing this technology.”

McAfee began working with synthetic polymers as a career in 1989, first with The Dow Chemical Company followed by a stint with the Chase Elastomer Corporation in 1994, both of which he credits for inspiring his interest in rubber-plastic composites. Wanting the freedom to dictate his own schedule and choose projects more suited to his interests, McAfee decided to break away from the corporate structure in 1996, when he and his wife, Debbie, founded McAfee Consulting.

While McAfee handles the research and analysis in the lab, Debbie oversees the legalities and financial side of things, a partnership that has kept their company thriving even when recessions and other adverse national events bring the economy to a crawl.

“Debbie brings a completely different knowledge and skill set to the table, and we make a great team,” McAfee said. “I’m blessed to have her in my life. It’s always easier to be in business when the cash is flowing, but the biggest challenge is staying in business when it isn’t. That’s where you learn what you’re made of. You also learn that failure isn’t an option, stopping isn’t an option, quitting, going back — those are unacceptable outcomes.”

McAfee remains humble about the success he’s seen as an entrepreneur, inventor and researcher. He says he simply chased the science and followed the opportunities it presented, a journey he insists truly began when he came to Texas A&M in 1985 for his Ph.D. in chemistry. World-class professors and the competitive nature of his peers helped set the standard for his career.

“I wanted to be on the world stage at the best place there is for chemistry, and that was Texas A&M University,” McAfee said. “Iron sharpens iron, and the best make each other better. Texas A&M had it all, and it made me, in my opinion, the scientist I am today.”

This article by Chris Jarvis originally appeared on the College of Science website.