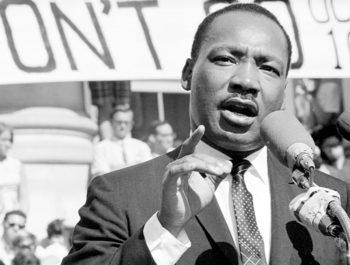

What Martin Luther King Jr. Said About Systemic Racism

Martin Luther King Jr. often spoke about institutional and systemic racism, saying that true racial equality cannot be reached without “radical” structural changes in society, says a Texas A&M University sociology professor.

“Justice for black people will not flow into this society merely from court decisions nor from fountains of political oratory…White America must recognize that justice for black people cannot be achieved without radical changes in the structure of our society,” King wrote in an essay published in 1969 titled “A Testament of Hope.” In his 1958 book Stride Toward Freedom, he wrote, “True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice.”

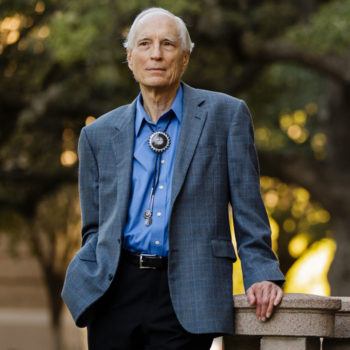

Joe Feagin, the Ella C. McFadden Professor in Sociology and Distinguished Professor, said those are just two of the many times King spoke of structural changes needed to achieve equality, but first and foremost of the need for white and Black people to agree on what “equality” actually means.

Feagin said King noted in a speech not long before his 1968 assassination that a major problem was getting white people to understand the meaning of the civil rights movement because there isn’t even a common language when the term “equality” is used.

King said that many white people, even well-meaning people, think that equality means Black people have to improve.

Feagin said King’s commentary on what equality means to many white people, and how some do not want to face that, is as accurate now as then.

“We whites created slavery, Jim Crow segregation and contemporary racial discrimination over 400-plus years now,” Feagin said. “Whites are the main racial villains in this story and have most of the political and social power to change that racial discrimination and inequality now. We cannot have a truly free and democratic society, with ‘liberty and justice for all’ until we do that.”

“The first step to do that is for whites of all ages to learn an honest history of this country’s systemic racism and the Black movements against it—something many whites today are not even willing to begin doing.”

Feagin said holding white people accountable for the promises of freedom and equality made by the founding fathers was a major theme in King’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech at the nonviolent 1963 protest March on Washington.

“Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation,” King said in front of the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963. “But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.”

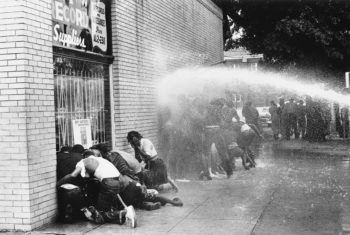

King referred to discriminatory treatment of Black people by police saying, “We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.”

Police brutality is a systemic problem, Feagin said, noting the March on Washington was all about institutional and systemic change to advance things like job training and voting rights, and to end workplace discrimination and segregation.

The Southern Poverty Law Center published a report evaluating the educational standards for teaching about the civil rights movement in all states and the District of Columbia. “They found the typical efforts on the part of mostly white legislators and educators in most states were to ignore or superficially review this important human rights movement and its racist context,” Feagin said. The report noted instruction was mostly limited to Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks and that only a handful of states required significant attention on the movement and the lessons it can teach about citizenship.

Feagin said avoiding teaching about the civil rights movement, or not exploring it thoroughly, goes against what King said: “He argued that if racism is ever to be eradicated, white people ‘must begin to walk in the pathways of [their] black brothers and feel some of the pain and hurt that throb without letup in their daily lives.'”

Feagin said, “How can we feel their pain without learning about it?”

Media contact: Lesley Henton, lshenton@tamu.edu