A Potential End To Postpartum Depression

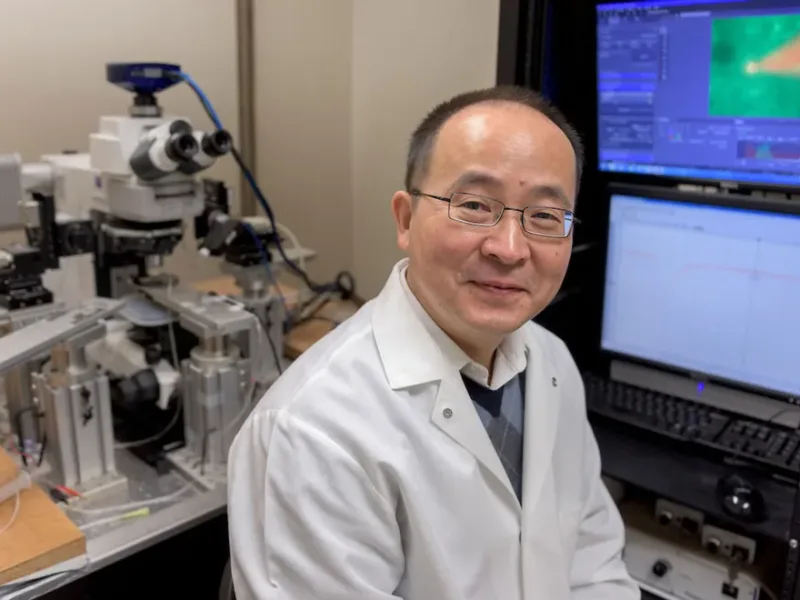

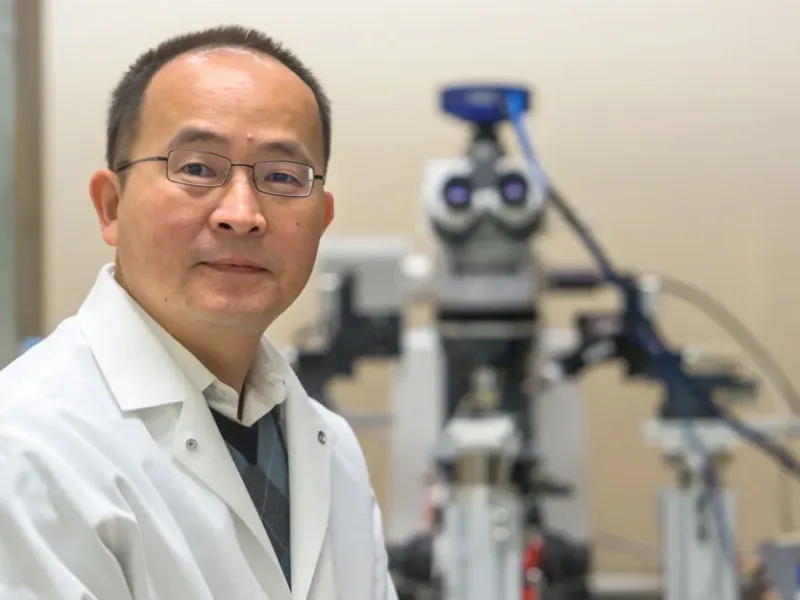

Postpartum depression affects about one in eight women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. D. Samba Reddy a professor in the department of Neuroscience and Experimental Therapeutics in the Texas A&M University College of Medicine, is the lead researcher of a lab that may have discovered a treatment for postpartum depression, which has historically gone largely undiagnosed and unaddressed.

Over the last two decades, Reddy has conducted extensive research to develop a new treatment method that makes use of the body’s natural chemistry to treat brain diseases. He coined this term “neurosteroid replacement therapy” to reflect the methodology of other, more-familiar types of replacement therapies, such as insulin replacement therapy or hormone replacement therapy. His most recent work applying this approach to postpartum depression is outlined in a paper recently published in the Journal of Neuroendocrinology.

Neurosteroids are steroids synthesized within the brain that have important regulatory effects on the brain’s function. One specific neurosteroid, allopregnanolone, is produced in increasing amounts during pregnancy. However, after childbirth, the neurosteroid levels drop, leading to chemical imbalances in the brain that can cause postpartum depression. Enter what could be one of the most groundbreaking discoveries in women’s health: the formulation of allopregnanolone, in injection form, for treatment of postpartum depression. This medication, which was then renamed as brexanalone, was approved in 2019 as the first drug for postpartum depression.

How Does The Medication Work?

Postpartum depression is unique in that there is a small window of time during which it can be treated; it varies from person to person, but the critical period is the first four weeks after the baby is born. The new mother’s body resumes the menstrual cycle after four to six weeks, and once the cycle starts, the body will start producing neurosteroids at normal levels again, and the new mother’s body is able to establish a rhythm.

“Before neurosteroid replacement therapy, there was no medicine available that worked quickly enough to treat postpartum depression,” Reddy said. “After childbirth, women don’t have weeks to wait on existing depression medications, which take at least three to four weeks before they take effect.”

Neurosteroids, on the other hand, work immediately as antidepressants because they have a rapid mechanism of action. They enhance an already-existing receptor in the brain, so when the drug is infused, the patient immediately starts feeling better, and after the recommended three-day duration of treatment, they’ll continue to feel better for weeks. This medication helps new mothers replace their neurosteroids for the first few weeks after birth until their bodies restart production of these neurosteroids naturally.

Why Is Postpartum Depression A Public Health Issue?

New mothers generally return home after a few days in the hospital, during which time they may or may not show the full symptoms of postpartum depression. As a result, and because new mothers are unlikely to report symptoms themselves, postpartum depression is a condition that needs to be identified by people observing the mother day-to-day. A partner, parent or friend may notice that the new mother is experiencing difficulties bonding with the baby, communicating her feelings or carrying out daily activities, and recognize that she needs help.

Therefore, it is vital that the public is made aware of both the symptoms of postpartum depression as well as the treatment that is available. In the past, postpartum depression wasn’t commonly acknowledged because there was no good solution.

“You don’t want to improve awareness about a problem when there’s no treatment,” Reddy said. “Telling someone that they have a disease but there is no treatment available can scare them.”

With the advent of this treatment, raising awareness of postpartum depression is an important component of how the public can address this pressing concern.

“With reassurance that there is a treatment available, I think women will feel more empowered to talk about postpartum depression and seek the help they need,” Reddy said.

This article by Sunitha Konatham originally appeared on Vital Record.