A Trailblazer In Black History Education

Albert Broussard wanted to be a teacher for as long as he could remember,

Initially hoping to teach high school, he instead decided to attend graduate school after finishing his undergraduate career at Stanford University, where he took his first Black history course in 1970.

“Black history was just being introduced into college curriculums, as were African American studies programs,” he said. “It was something I increasingly became interested in. After that, I wasn’t sure I wanted to teach high school any longer.”

When looking back at what inspired him to study and teach Black history, Broussard cites the trajectory of the Black experience as being key to his decision.

“People were forced into labor coming from Africa an ocean away and yet they adapted, using wit, creativity and humor to persevere,” he said. “And post-Civil War, even though things didn’t go as they’d hoped, they continued to make progress, however slowly that may be. To me it was just a tremendously inspiring story.”

After completing his education — he was among the first three Black students to complete his doctoral program in 1977 — Broussard served as director of the African American studies program at Southern Methodist University. He was then recruited to join the faculty at Texas A&M University in 1985.

“I was able to introduce the first Black history courses taught at Texas A&M, and with the exception of a few semesters, I’ve never taken a year off since I started teaching here,” Broussard said.

He had already been among the first professors to teach Black history at most of his previous universities, including the University of Northern Colorado and the University of California, Davis.

“I think you just have to put any reservations behind you and realize that sometimes, you have to be the trailblazer,” Broussard said.

Throughout his career, Broussard has written many of the history textbooks used in grade schools across the nation. His textbook writing career began 25 years ago when a friend with the Senate Historical Office asked him to co-author a textbook under McGraw Hill.

In 2020, after decades of authoring what he estimates to be dozens of textbooks for middle and high school students, he made the decision to begin capitalizing the “b” in Black. It’s a move that many major media outlets have made in the last year — the Associated Press changed its style guide last June to capitalize the “b” when referring to Black people in a racial, ethnic or cultural context.

Broussard said this change relates to “areas of self-construction,” in which one constructs their own identity. With a new textbook edition set to roll out in 2023, Broussard hopes to convince his own textbook editors at McGraw Hill to follow suit and do the same in their works, a serious area of debate and discussion.

“I think it’s important because it’s what most Black people call themselves; they call themselves Black people,” he said. “Language changes all the time. Words that weren’t in fashion five or 10 years ago are viewed as perfectly legitimate today.”

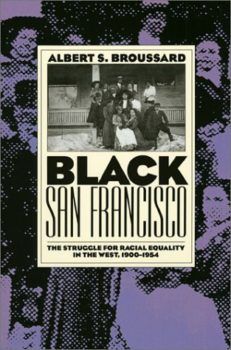

Aside from his continued work as both a textbook author and esteemed Texas A&M professor, Broussard continues to be an active independent author, currently writing a history of African Americans in California from 1945 to the present, a historical study that looks at the shift of Black communities from the North and South to the West Coast. His first published book focused on the Black community of San Francisco in which he grew up.

Broussard has inspired several students to pursue careers in researching and writing Black history, too.

One of his former students is author Caleb McDaniel, who won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in History, and Craig Flournoy, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for his work at the Dallas Morning News.

“A mentor is neither a father-figure nor a mother, but someone who takes an active interest in the learning and inquisitiveness of his students,” Broussard said. “The truth of the matter is that we never know how our learning styles will impact a student until they tell us. It is important to mentor all your students to the degree they are willing to learn and allow themselves to be challenged instead of simply going through the motions. I learned decades ago to never underestimate the impact that you, as a professor, could potentially have on a young mind, but I do not delude myself either.”

This article by Amber Francis originally appeared on the College of Liberal Arts website.