How Pandemics Affect Societies

Before Western medicine, pandemics occurred every 10 to 50 years. But while pandemics have historically resulted in the death of a significant portion of the population, they’ve rarely resulted in major societal changes, says Texas A&M University professor Samuel Cohn.

Cohn, who studies both general historic and development sociology, said this is in part because pandemics typically follow a mortality pattern that targets the oldest and youngest members of the population.

While any death is cause for concern, he said, population numbers tend to recover quickly from the death of older adults, children and infants.

“No society has died of a pandemic,” Cohn said.

Cohn is a professor in the Department of Sociology in the College of Liberal Arts. His forthcoming book, “All Societies Die: How to Keep Hope Alive,” examines the downfall of societies.

Now, the COVID-19 pandemic has had an unusual mortality pattern in that it has affected relatively few infants and children. Even so, society’s reaction to the novel coronavirus is not much different than the Romans’ reaction to plagues, Cohn said, with some individuals who have the means to avoid contact with other people choosing to isolate in rural areas until it’s considered safe to return to cities.

“That is the classic anti-pandemic approach of pre-industrial societies. The wealthy move from the city to country villas with the intention of not coming back until the coast is clear,” Cohn said. “Many poor people would have families with farms, so in a more modest version, you go home to get out of the city. Even before modern medicine, you could avoid real wipeouts by simply bailing out of town.”

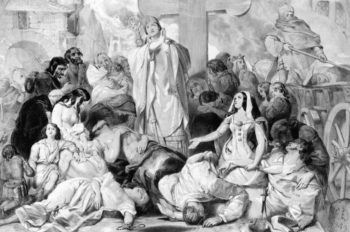

While most pandemics have few lasting societal influences, they often result in increased religious practice. This is usually because people turn to religion to help explain the unexplainable and feel a sense of serenity in situations they cannot control, he said. Some religious leaders have even used pandemics as an opportunity to spread their faith.

“The Christians took care of a lot of Romans who were being hit by prime age mortality in much of the 100s to 300s of the Roman era, which was what gave the Christians a good reputation for being charitable,” Cohn said.

The Black Death, a global epidemic of bubonic plague in the mid-1300s, was one of the few pandemics that had a profound effect on society. Cohn said it marked the ending of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance. This is because mass prime-age adult deaths made farmers who were previously dependent on feudal lords more independent.

“Lots of people died, and suddenly the farmers were scarce,” he said. “The nobles needed their labor, which gave the farmer bargaining power for the first time. The first thing they did was say, ‘We’re taking the right to leave. If we’re scarce, that means someone else wants me.’ Suddenly they were moving and there was a creation of the capitalist labor market. Furthermore, there was an increase in consumer expenditure giving merchants more business. Not all plagues have such a happy ending.”

While Cohn credits the Black Death with important socioeconomic shifts, he also points out that it was traumatic to live through.

“During the Black Death, death was not contained in some kind of critical care unit where your family didn’t see it,” Cohn said. “Parents were watching their children with bubonic plague cry and cry and slowly die. As soon as one family member died, buboes would begin popping up on another loved one’s face. This was an experience that was etched in the psychology of everyone who saw this, and that led to religious thinking and cultural thinking. It was a profoundly traumatic experience.”

We now place the responsibility and burden of caring for the critically ill on the healthcare system. Cohn said the traumatic experience for many during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the realization that Western medicine doesn’t immunize us from pandemics or mass mortality.

“With the rise of modern medicine came a sense of efficacy over being able to control your mortality,” Cohn said. “If I eat healthy, if I exercise, if I drive safely, if I don’t smoke, I can protect myself from premature death.”

When our sense of control over our own mortality is shattered, society tends to take on a more fatalistic view of life. Cohn explained that people with this mindset may believe that taking chances equates to bravery. This way of thinking about morality is the “historic normal,” he said.

The return to the “historic normal” psyche has been exhibited in America by individuals who are reluctant to follow safety guidelines like mask mandates and stay at home orders. Team oriented countries like Switzerland, Japan and Singapore have done a better job of following COVID-19 safety guidelines, according to Cohn, because there is a collective cultural understanding that teams can accomplish more than individuals.

Despite high COVID-19 death rates, Cohn said, there likely won’t be an lasting societal changes from this pandemic.

“All things considered, I believe most people will fortunately view the pandemic as an exceptional time period and improved modern medicine as being the new normal,” he said. “If pandemics become more dominant and are far more normal than common diseases, then I think you would start seeing the changes. But I don’t think this pandemic is strong enough to do that.”

This article by Rachel Knight originally appeared on the College of Liberal Arts website.