Discovery Of Human Bone Has Historical Impact For North America

An unexpected discovery of human remains in the Caribbean by Texas A&M University at Galveston faculty members and students is providing new information on the Lucayan people, a group who inhabited the Lucayan archipelago well before European colonization occurred in the 15th century in North America.

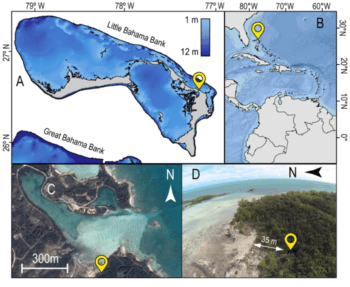

Analysis of the remains using a new age modeling technique dates the bone as being 100 to 200 years younger than previously thought. The remains were preserved in a sediment core sample taken from a sinkhole on Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas by Pete van Hengstum, associate professor in the Department of Marine and Coastal Environmental Science, and Richard Sullivan ’21, a Galveston Campus doctoral student in the Department of Oceanography. It is only the second discovery of Lucayan skeletal remains on the island, and was a surprising find by a team working on climate change research.

When the core sample was first analyzed, “an undergraduate student called the office and said, ‘We have rock,’ but it wasn’t a rock – it was human remains,” van Hengstum said. “We were expecting mud and maybe fish bones. There were no large animals like cows or horses on Great Abaco Island in prehistoric times, so this find is hugely significant for a number of reasons.”

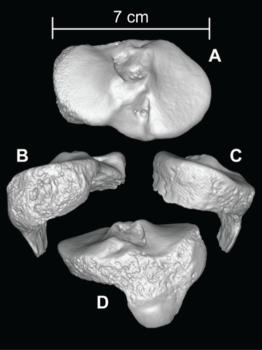

Further analysis determined the fragment to be of a right tibia, or the leg bone that comprises the shin. Sullivan, a coastal geoscience doctoral student, calibrated the direct radiocarbon age of the bone by combining multiple dating techniques to create a new method for determining the age of the Lucayan skeletal remains.

The results confirmed the team’s hypothesis that the bone was aged to the Lucayan Period. However, they were surprised to discover that the weighted median calibrated ages placed the bone as belonging to a person who inhabited the island between 1290 and 1295 CE, while previous dating models would have placed the remains between 100 to 200 years older.

Sullivan said the chemistry of the bone pointed to the individual having a diet that consisted of fish and marine constituents, along with terrestrial plants like fruits, berries and roots. This fact, combined with the high quality of the 22 radiocarbon ages discovered in the rest of the sediment infill that surrounded the bones, allowed him to stand by his model’s conclusion with confidence.

“We didn’t date the bone initially. We were wary about sending it out, but we dated the leaf matter around it using the standard metrics we use to date our sediment cores,” Sullivan said. “We had a good idea then that previous approaches of dating Lucayan skeletal remains didn’t fit, so it gave us our first clue about ‘there is something we’re not considering here.’”

The technique can be retroactively applied to all Lucayan skeletons ever recovered from the Bahamas. The Lucayans were the first American inhabitants encountered by Christopher Columbus, and were entirely removed from the Bahamas by the mid-1520s due to enslavement and disease. This has made determining an accurate calendar age for the migrations of these indigenous Caribbean people difficult.

“Accurate dating problems are unfortunately not new and spans disciplines,” said van Hengstum. “We know that Columbus wasn’t the first person in the Americas or the Bahamas. This skeleton is a piece of North American history.”

The discovery was serendipitous for the group of climate researchers focused on using sinkhole sediments to determine long-term changes in rainfall and hurricane activity. While not their main field of research, they included the findings in their recently-published paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science in hopes it provides archeologists with a more accurate means of calendaring indigenous people groups in the Caribbean.

“We’re doing climate research, not archaeology, but we obviously felt a sense of responsibility to follow this up and do it right,” van Hengstum said. “We won’t be going back to that specific site at this stage, but this emerges as a site others might be interested in going back to or further exploring. We sincerely hope they do.”

Over the last decade, van Hengstum has worked to study and apply the sediment and meiofauna found in caves, blue holes and sinkholes to study problems in climate science, history and landscape change. His research has led to a greater understanding of the development of extreme weather activity like rainfall and hurricanes in the Bahamas and Caribbean.

Media contact: Andréa Bolt, a_bolt@tamug.edu