Can The President Really Order Troops Into US Cities?

Speaking from the Rose Garden Monday evening, President Donald Trump suggested that he would deploy the U.S. armed forces to bring to heel the states and cities where he views governors have responded inadequately to the widespread protests in response to the death of George Floyd.

“If the city or state refuses to take the actions that are necessary to defend the life and property of their residents, then I will deploy the United States military and quickly solve the problem for them,” Trump said.

The Insurrection Act of 1807 does give the president powers to deploy the military domestically under certain circumstances. But it’s been used rarely, and in most cases at the request of a state’s governor.

What The Law Says

Lynne Rambo, professor emerita at the Texas A&M University School of Law, said a president can invoke the Insurrection Act under five circumstances.

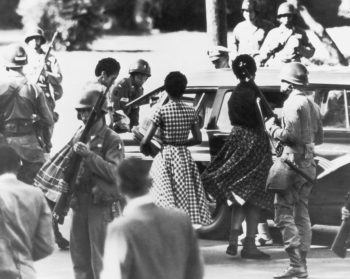

First, if there is a fear of action to overthrow a state, the president can send in troops if a state legislature asks him to. Second, the president can do so at the request of the state’s governor if the legislature cannot convene. In the third circumstance, if there is a threat of federal law being broken, the president could also deploy the military. Rambo said this section was used by Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy against Arkansas, Mississippi and twice in Alabama when the states refused to desegregate schools.

Under the fourth and fifth circumstances, Rambo said the president can invoke the act if there is domestic violence that threatens the rights of any “part or class of the people,” and the “constituted authorities of that state are unable, fail, or refuse to protect” rights, privileges or immunity, or if the domestic violence opposes or obstructs the execution of federal law.

So without the request of a state legislature or governor, would Trump be able to send federal troops into a city or state?

“He would have to be able to say either that some federal law was being broken or obstructed,” Rambo said. “In contrast with the desegregation situations, he doesn’t have any obvious federal law to claim is being broken. To solve this problem, I would look for him to invoke protecting federal property in the states in question.”

Rambo said the president might also say that state authorities are refusing or failing to protect the rights of a class of people.

“There you would look for him to invoke the rights of anyone whose property is being damaged, but he would also have to be prepared to say that the states were refusing or failing to protect the rights of those owners, a rather controversial declaration,” she said.

Historical Use Of The Insurrection Act

For Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act now would be “the height of unusual,” said Texas A&M Professor of History Elizabeth Cobbs.

Cobbs, a historian of American and world history, said previous versions of the Insurrection Act have dated back to the founding of the government, which was formed partly due to rebellions in which states were unable to control their own populations.

“One reason for calling a Constitutional Convention was because of Shay’s Rebellion in 1786-87. Essentially the state of Massachusetts did not have enough local militia willing to defend the state,” Cobbs said. “The federal government didn’t have any military either at that point, once the American Revolution was over. That’s when the Constitutional Convention was called, to find a way to develop the means necessary to preserve the union.”

This was followed by the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, in which President George Washington personally led troops to western Pennsylvania to put down the uprising. Cobbs said “part of the point” of having a Constitution was to create the necessary military force to defend the government when threatened internally.

This was also the spirit of the Alien and Sedition Acts at the end of the 18th century. And then there was the 1806-07 conspiracy of Aaron Burr, who plotted with foreign agents to seize territory on the Southwestern border of the United States to create an independent country. This was the broad context in which the Insurrection Act was passed in 1807.

“There was this continuing threat of insurrections, which weren’t what we would call civil disobedience today,” Cobbs said. “These were armed gatherings of people trying to raise armies, essentially, to overthrow governments.”

In the 20th century, Eisenhower and Johnson used the act in cases where the civil rights of minorities were not being protected by the states, Cobbs said, like when troops from the 101st Airborne Division were sent to Little Rock, Arkansas, to protect students who were “unable to go to school, literally, without the protection of the U.S. Army.”

“It’s been used super rarely — in fact since the mid-1960s, the only time the United States has sent troops has been at the request of counties or states that have said, ‘we need help,’” Cobbs said. “But the United States government actually imposing the American military against a state that doesn’t want it, in the last 100 years that’s only happened when the states would not abide by the federal law to implement amendments to the Constitution in the case of black civil rights.”

So for Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act in the context of current events would be “very unusual,” Cobbs said.

In the case of the protests focused on racial justice and police brutality in the wake of the death of George Floyd, a black man who was killed after a white police officer in Minneapolis pinned his neck with his knee for several minutes, the unrest has spread across the country.

“This is not an incident limited to one locale, where a hurricane has hit or a riot taken place, and the state or county asks for help,” Cobbs said. “This is very different. The scenario Trump has suggested is more akin to 1861, when the entire South was invaded and occupied by the federal government.”

For Trump to imply that he will send troops “anywhere and everywhere in the United States” that he decides needs them is “really extraordinary,” Cobbs said, because there’s no precedent aside from the Civil War.

In this case, there are no states or localities rebelling against federal law or amendments to the U.S. Constitution, nor are they asking for help with a natural disaster or uncontrolled uprising, she said.

“So nobody’s asking for help, and these state governments are not insubordinate to the United States of America,” Cobbs said. “Those are the only two situations in which this has ever been implemented, so that makes it really unusual and untoward.”

Media contact: Caitlin Clark, caitlinclark@tamu.edu