30-Year-Old ‘Snail Mail’ Leads To Collection Of Extinct Species Discovered By Texas A&M-Galveston Professor

When Tom Iliffe checked his email a few weeks ago, he read a message about a collection of 30-year-old snails.

This message came to Iliffe, a professor in the Department of Marine Biology at Texas A&M University at Galveston, from Collection Manager John Slapcinsky of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Slapcinsky was inquiring about a collection of Pacific Island snail samples Iliffe had collected more than 30 years ago in the South Pacific. Slapcinsky was helping clean out a vacant office and happened upon a collection of hundreds of snail samples gathered by Iliffe decades prior. He was floored.

A snail expert himself, Slapcinsky told Iliffe his collection could include several new species and perhaps the last-known records of now-extinct snails.

“Many Pacific Island land snails are endangered, and if you’re considering extinctions in recent times, half are mollusks, and most are land snails,” Slapcinsky said. “So we’re working with a consortium of different museums to gather information about collections of Pacific Island land snails because they’re such an endangered group.”

Slapcinsky is hard at work cataloging the specimens Iliffe discovered, but he needed help georeferencing the samples and their respective origins.

“I immediately wrote back to John, sending him a copy of my collection notebook from the trip listing the names, location (latitude and longitude), elevation, distance from the coastline and ecological description of each collecting site,” Iliffe said. “I’m incredibly excited to see where we can go from here with these specimens and the otherwise-irretrievable database they represent.”

The scientist took the specimens home and got to work, reviewing 700 samples representing from 5,000-7,000 individual shells he’s been busy identifying and cataloging.

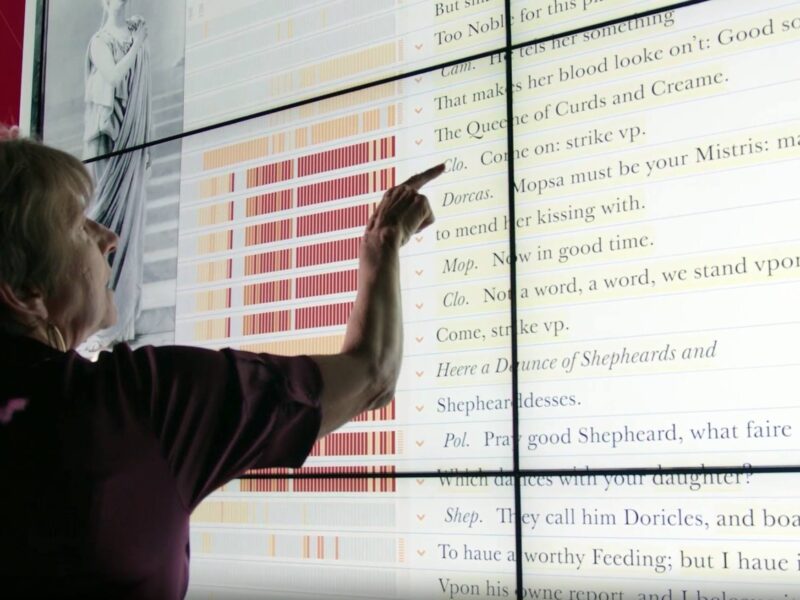

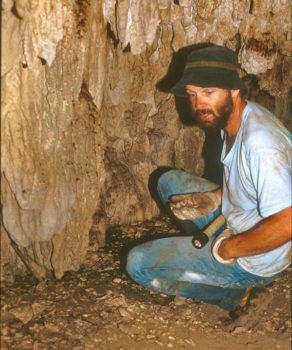

In 1987, Iliffe organized a year-long cave exploration expedition across 12 locations in the South Pacific. Iliffe specializes in the evolution and conservation of the biodiverse species inhabiting marine caves, as well as technical diving within the context of extensive cave systems.

He secured funding from the United States National Science Foundation (NSF) to explore and research underwater caves in Tahiti, the Cook Islands, Tonga, Fiji, Western Samoa, Niue, New Zealand, Southern Australia, Tasmania, New Caledonia, Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands. Iliffe spent roughly one month at each location.

During his explorations, Iliffe was in touch with officials at the museum and they encouraged him to collect whatever samples of the understudied animals he could find.

“Sometimes snails fall into cave entrances or shell deposits build up over time. Often, and even at that time, they’re locally extinct or fully extinct, so you would only find deposits in caves,” he said. “I kept a bag in my pocket, would go collect, preserve them appropriately, then be sure to detail everything I could. There was no GPS at that time, so I had topographical maps of the areas where I was. I plotted the areas as accurately as possible and included details about the collection site.”

Iliffe isn’t the only one concerned with snail conservation at Texas A&M-Galveston. Coastal ecology doctoral student Janelle Goeke studies marsh periwinkle snails along Texas’ Gulf Coast.

Specifically, Goeke researches how the periwinkles are responding to flora and fauna-based changes in their salt marsh environments. Like Iliffe and Slapcinsky, Goeke knows how it can be the smallest creatures that have the largest or significant impacts on their respective environments.

“They’re incredibly important in shaping salt marshes, as in high enough densities, they can actually consume all the plants in an area of marsh, eating it right to the ground and leaving the marsh bare,” Goeke said. “Here in Texas, the marsh periwinkles are one of the most important food sources for blue crabs, and are also consumed by some species of wading birds.”

Slapcinsky has done his own land snail field research in Hawaii and Papua New Guinea. He and colleagues from Hawaii were proud to discover and report the first new recent Hawaiian species of land snail described in over sixty years.

“We’ve got to do better while we still can,” he said. “We can’t afford to have things keep disappearing.”

Media contact: Andréa Bolt, Texas A&M University-Galveston, a_bolt@tamug.edu