Texas A&M Veterinary Students Practice Surgery At Home

The path to becoming a veterinarian is, by nature, very hands-on. Students first see and practice procedures on synthetic models, learning by experience and honing their skills safely before graduating to care for real animals.

But with the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching these essential skills has become more difficult. The transition to virtual learning distances students and instructors, a dynamic that can be difficult even in less experiential disciplines.

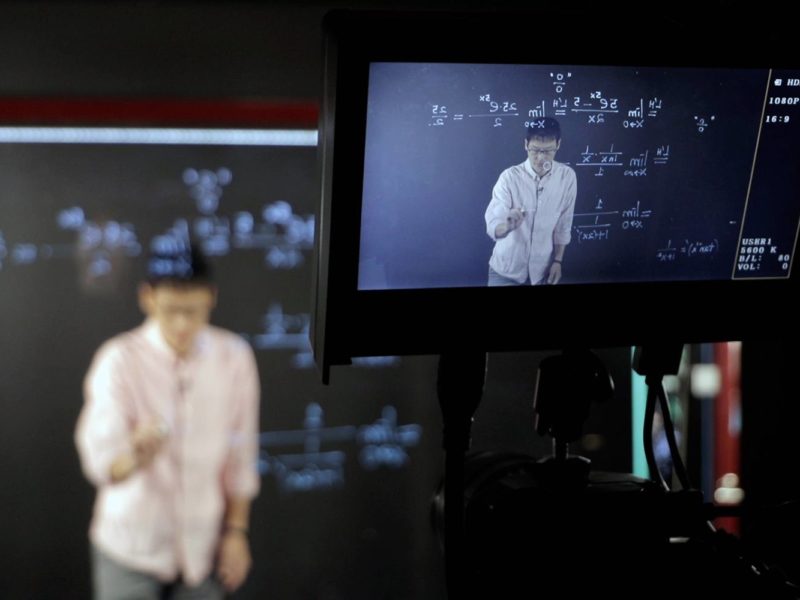

As the instructor of the Principles of Surgery course for second-year veterinary students, Dr. Kelley Thieman, an associate professor at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM), not only teaches the details of surgery through lectures, but also oversees the laboratory-based component.

“Usually, students will come to lab and, in their groups, prepare their ‘patient,’ a synthetic model with replaceable fake organs,” Thieman said, explaining how the laboratory component of the course operates under normal circumstances. “They gown, they glove, they drape in their patient, and then they do the procedure. The instructors circulate and discuss what they’re doing, give them pointers, answer questions and discuss certain decisions.”

Now, with courses moved online, students make video-conference appointments with their professor and “perform surgery” in their homes on segments of the synthetic model shared by their group.

“Each of the students sets up their own little operating room in their house,” Thieman said. “It’s so funny to get to see the students’ houses; their dogs and their cats are so interested in what they’re doing. We have cats that get into the surgical field and try to help out.”

Though both instructors and students in this course have demonstrated flexibility in adapting to new circumstances, Thieman has found it difficult to translate the finer details of surgery to a digital setting.

“I think the biggest challenge is seeing if their stitches are too tight or too loose; it is really difficult, because I can’t touch them,” Thieman said. “Surgery is such a tactile thing — teaching students and then being unable to check their sutures, their stitches, is difficult.”

Thieman is overcoming this challenge by directing the students on how to check their own stitches, requesting that students adjust their camera to a more advantageous position and that they measure the spacing between stitches using a ruler.

Lauren Minner, a second-year veterinary student in Thieman’s class, said that social distancing measures make such interactive teaching strategies difficult, as students are not only separated from their professors, but also from other members of their lab groups. This is especially challenging because groups that once shared a synthetic patient have to adapt to learning from the divided bits and pieces.

“During our labs, some of us have had to improvise what our organs are,” Minner said. “Some classmates have used things like dog toys or felt bags that they have laying around, and so we are having to improvise a little bit as far as our materials go, but I think that it makes it a little bit more fun. You’re having to imagine things, but at the same time you’re performing the same surgeries.”

Minner believes that the process of collaborating with her professors to complete coursework digitally has produced the unexpected benefit of increased understanding between professors and students.

“More than anything, it’s improving our relationships with our professors, because we all are having to work together and we all are giving each other feedback about how things are going,” Minner said. “It’s definitely opened up communication between ourselves and our professors a lot more. Once all of this is over, I think that all of us are going to have a better working relationship with one another.”

Thieman also thinks this experience can bring new insight to the veterinary field. One unexpected benefit offered is the possibility to improve the way veterinary medicine is taught and expand accessibility through remote learning.

“I still think that in-person lab is better, but there are times when that cannot happen,” Thieman said. “If we have a student who is sick or has to be gone for other reasons but they still want to continue their education, this could be really helpful for those students in the future.”

More personally, Thieman has found this experience to be an exercise in flexibility.

“I’ve learned to adapt quickly,” Thieman said. “I was a little skeptical when this all started that it would be a success, but I’ve learned that it’s totally doable; the students are getting a lot out of it, and we can do more by video than I thought we could.”

Media Contact: Jennifer Gauntt, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216