Are There Climate Change Clues In Texas Hill Country Cave Stalagmites?

The Texas Hill Country is full of caves, and those caves could be full of clues to Earth’s past climates.

Christopher Maupin, a research associate in the Department of Geography at Texas A&M University, has been travelling since 2015 to Williamson County, Texas, where he has been utilizing caves to study climate in the Southern Great Plains region.

By studying water isotopes in caves, Maupin’s research team is able to reconstruct through time the history of the isotopes before the preindustrial era.

Working in collaboration with environmental consulting firms SWCA and Cambrian Environmental, which provide surveys and evaluations for the county, the Texas A&M team was granted access to work on a private land preserve to conduct research in the caves. The Williamson County Conservation Foundation supports this work both logistically and financially in hopes that they can find out what has happened in the past to the hydroclimate of their region, Maupin said.

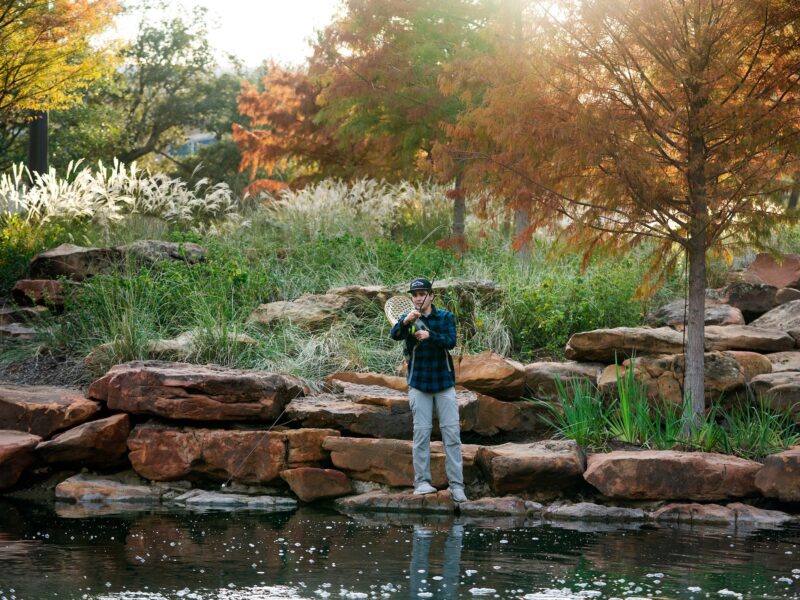

During the team’s most recent trip, in May of 2019, two students who are currently research assistants in the Stable Isotope Geosciences Facility conducted research nearly independently, with Maupin’s supervision.

“I want to, at the very earliest possible point in their scientific endeavor, instill them with the understanding that they should be free and encouraged to use their creativity to look at scientific problems,” Maupin said.

The Southern Great Plains is an important region to study because it is made of “a huge population of highly water-stressed individuals and economies,” Maupin said. “If we know what isotope values each different storm type can produce, then we can really say ‘okay, we have a probability here of what kind of storms these were, what kind of storms these were that dominated whenever these cave deposits were growing.’”

To fix the scale issue, Maupin said that there are two proposed strategies: making the models finer scale, and using paleoclimate to evaluate past climate to pinpoint how much variability the Southern Great Plains Climatology is capable of.

“When you’re trying to build a house, you use many different tools, and when you’re trying to understand the climate system, you use many different tools. Stalagmites are one of those tools,” Maupin said.

“It’s an interdisciplinary effort wrapped around a very tight but important scientific question and that is: How are we going to handle the next 30-100 years? What are we going to have to weather? Can we reduce the uncertainty of that?” Maupin said.

Using this data, they can reconstruct the history of the water isotopes as they enter the caves during and following storms.

“So, we’re looking at how the isotopic evolution of Texas has changed and been controlled and been tugged on by things like Ice Ages or orbital forcing or abrupt climate change because of the incredible importance of storms to our livelihoods in the Southern Great Plains,” Maupin said.

Maupin hopes that through paleoclimate research, they can “use the past to understand as much about the present as we can, and proactively plan for the future.”

Media contacts:

- Leslie Lee, College of Geosciences, (979) 845-0910, leslielee@tamu.edu

- Robyn Blackmon, College of Geosciences, (979) 845-6324, robynblackmon@tamu.edu