Fast Facts: Flesh-Eating Bacteria

Although not an everyday occurrence, the phrase “flesh-eating bacteria” seems to flash across the evening news every few weeks. Hector Chapa, MD, FACOG,clinical assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Texas A&M College of Medicine, discusses this frightening phrase and what it means for our fun in the sun during these hot months.

What are flesh-eating bacteria?

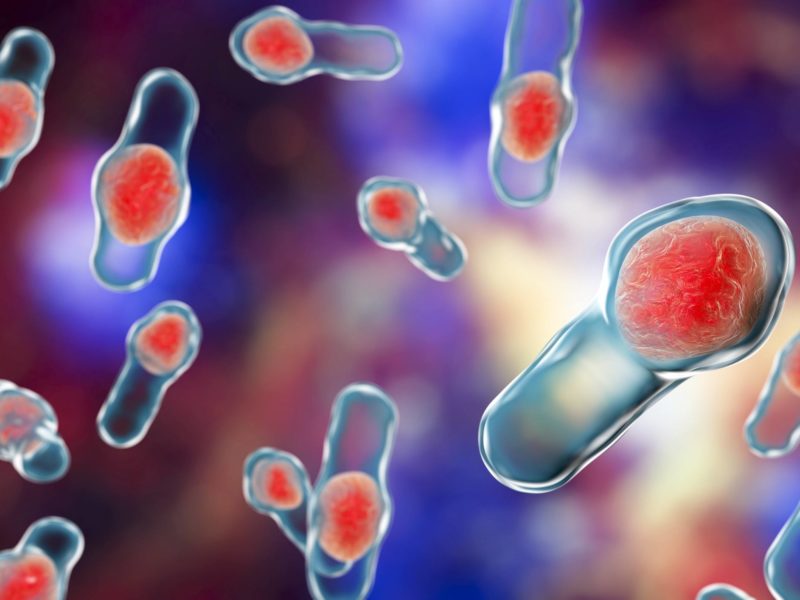

In general, the phrase ‘flesh-eating bacteria’ refers to a tissue-destroying infection called necrotizing fasciitis. Since 2010, approximately 700 to 1,200 cases occur every year in the United States. Furthermore, roughly one in three people who contract it die from the infection.

“With a quick diagnosis, rapid treatment and fast surgery, flesh-eating bacteria does not have to be fatal,” Chapa said. “The trick is to quickly identify it and seek immediate help.”

What are the different kinds of flesh-eating bacteria?

Various types of bacteria can cause flesh-eating bacteria. However, the two most common causes are Group A streptococcus and vibrio. These bacteria can live in lakes, oceans, swimming pools and even hot tubs.

Group A streptococcus is a bacterium also known to cause strep throat, scarlet fever and rheumatic fever. While spreading this bacterium through strep throat is relatively common, spreading necrotizing fasciitis is rare.

“Vibrio, or vibrio vulnificus and vibrio alginolyticus, is the bacteria associated with the summertime seawater exposures of flesh-eating bacteria that are currently in the news,” Chapa said. “You can contract vibrio from salt water or brackish water, but also from eating raw or undercooked shellfish.”

Both types of bacteria can cause an infection to enter the system through breaks in a person’s skin. This break in skin can be something as small as an insect bite or scrape, but also something as large as a surgical incision.

What are the symptoms of flesh-eating bacteria?

A flesh-eating bacteria infection can spread quickly. The first signs of an infection are an increasingly large presence of red or swollen skin. The red skin will be painful, and its appearance will be followed by a fever.

Symptoms of a more progressed flesh-eating bacterial infection are ulcers, blisters or black spots under the skin. Another symptom is the presence of pus oozing from the infected area. People affected also feel dizzy, fatigued and even nauseous.

“If you notice a combination of these symptoms, whether you have been in the ocean or not, then contact your health care provider immediately,” Chapa said. “With flesh-eating bacteria, you want to get help as soon as possible.”

Are certain people more susceptible to flesh-eating bacteria than others?

Overall, this infection is rare. However, it can happen and it is life threatening.

“People with impaired immune systems—like those with cancer, uncontrolled diabetes or any variety of autoimmune conditions—are more likely to contract flesh-eating bacteria,” Chapa explained. “These high-risk people are also more likely to develop a more serious infection from it as well.”

How do you treat flesh-eating bacteria?

“Antibiotics and surgery are the first line of defense if someone contracted necrotizing fasciitis,” Chapa said. “However, if the infection has killed too much tissue, then a surgeon may need to surgically remove the dead tissue to prevent it from spreading.”

In serious cases, you may need a blood transfusion and multiple surgeries to successfully get rid of necrotizing fasciitis.

How do I avoid contracting flesh-eating bacteria?

If you have an open wound, health care providers will recommend you avoid going in the water. “However, if you do go in water, it is very important to completely rinse off and wash yourself with soap,” Chapa said. “Also, watch your skin for any unusual changes or sores, especially if you have a compromised immune system.”

Lastly, before going to your local lake or beach, check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website for health alerts.

This article by Mary Leigh Meyer originally appeared in Vital Record.