Bush School Students Travel To Kenya, Tanzania To Present To USAID On Food Fortification

In Tanzania, 35 percent of children under the age of five experience stunted growth due to malnutrition. Sixty percent of children are anemic, a condition widely attributed to iron deficiency in their diets. In bordering Kenya, the situation looks regrettably similar. Largely, these conditions are caused by a lack of enough food or a lack of nutritious food. This not only affects children, it affects populations globally. Food insecurity is a major problem in many parts of the world, and East Africa is no exception.

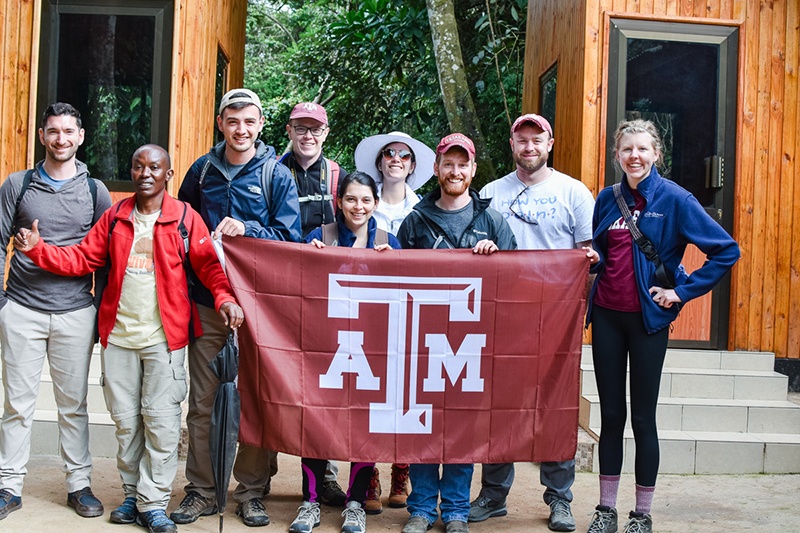

A team of students at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University, led by Morten Wendelbo, a Research Fellow at the Scowcroft Institute of International Affairs, began research in January on food fortification to address this problem following a directive from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The team was comprised of first- and second-year students from the international affairs and public service and administration programs. Recently, the team traveled to Kenya and Tanzania to do further research and present their findings to USAID and local government officials and community members. The researchers sought to better understand how micronutrient malnutrition could be addressed through food fortification and the associated challenges of fortifying certain types of food in the two East African countries.

“Micronutrient malnutrition might sound like a scary technical term,” said team member Seth Smitherman, “but really it is just indicative of a chronically poor diet.”

Food gives a person both macronutrients (like carbs, fats, and proteins) and micronutrients (like iron, zinc, and Vitamin A). Malnourishment is a likely outcome when diets lack these critical micronutrients. In children, malnourishment can manifest itself in stunted growth and anemia and can severely reduce the immune system’s ability to function, resulting in higher rates of infectious disease.

To ensure populations receive the micronutrients they so desperately need, many who work in development turn to food fortification, which is the practice of deliberately increasing the content of an essential micronutrient (like vitamins and minerals) in a food to improve the nutritional quality of the food supply.

The Bush School team looked specifically at the fortification of maize in Kenya and Tanzania, examining current practices, legislation, and the culture in both countries to determine possible solutions to micronutrient malnutrition. Maize is a staple of diets in both countries.

The political will necessary to push fortification of maize forward is present in both countries. “There are rules that require the largest maize millers to fortify their flour,” said Smitherman. “The biggest challenge, and the reason we got involved with this topic, is to try to scale fortification to the small millers, which currently lack the means and desire to fortify [their maize].”

The team’s report finds that while large-scale mills are mandated to fortify their maize flour, that doesn’t necessarily translate to consumers purchasing fortified flour.

The report’s chief purpose was to determine whether the governments in these countries are a sufficient catalyst for food fortification. Despite the presence of political will, they found many challenges with the government serving as a primary motivator.

Some challenges include confusion about what constitutes fortified flour and a cultural disinterest in purchasing the fortified product. Tackling these problems is ultimately essential to changing the way Kenyans and Tanzanians think about fortified products and is the first step toward addressing micronutrient malnutrition.

The purpose of the report was not necessarily to make recommendations to USAID, said Smitherman, but to assess the current situational climate and report the findings. The report focuses on eight to ten constraints. While the team did make recommendations, they are not the primary feature but are drawn from and support the legitimacy of the highlighted constraints.

This article originally appeared on the Bush School website.