New Book By Professor Emeritus, Outstanding Alum Details Creation Of Historic Texas A&M Buildings

A bohemian Texas A&M University architecture professor, scores of unemployed Depression-era artisans and millions of West Texas oil dollars combined to produce a jewel-box collection of 10 university buildings that renowned theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking once declared “magnificent.” All built from 1929 to 1933 and in full use today, they are perhaps the finest buildings on the massive College Station campus.

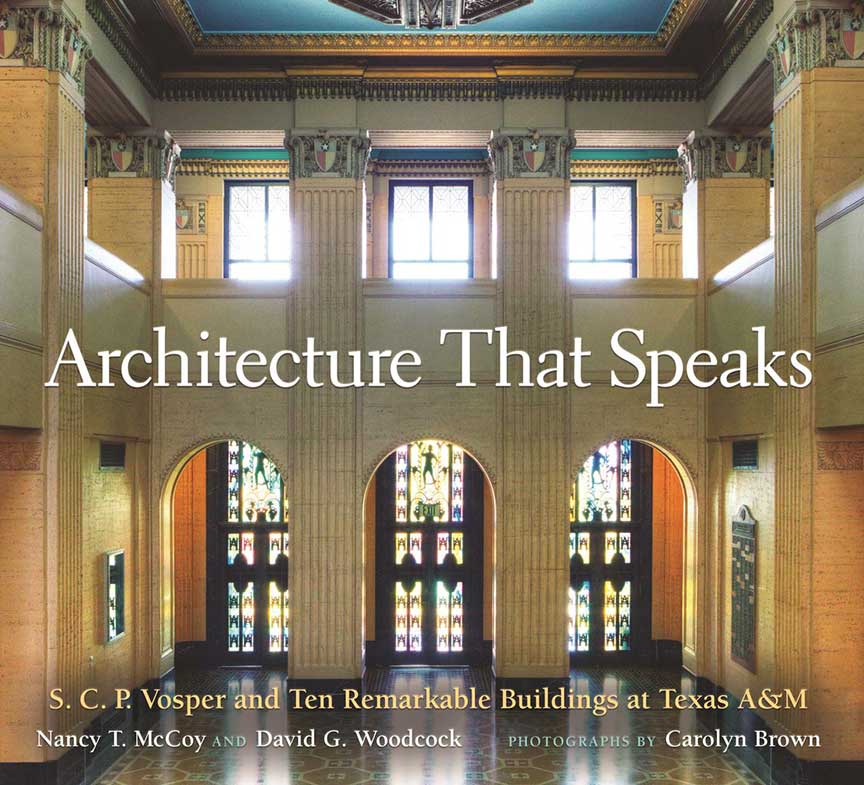

The intriguing tale of the buildings’ creation is colorfully told in the new book “Architecture That Speaks” by Nancy T. McCoy ’81, founding principal of Quimby McCoy Preservation Architecture LLP, and David Woodcock, Texas A&M professor emeritus of architecture, with sumptuous illustrations by Carolyn Brown, an architectural and fine arts photographer.

A reception marking the publication of the book and an exhibit of Brown’s photographs took place Thursday, Sept. 28, 2017, in the James R. Reynolds Gallery on the second floor of the Texas A&M Memorial Student Center. The exhibit will continue at the gallery through November 4.

The star of the book’s circuitous story, published by Texas A&M University Press, is the very eccentric architect Samuel Charles Phelps Vosper, affectionately known as “Sammy Sunshine” by students and professional colleagues alike for his “hail fellow, well met” joviality and uninhibited behavior.

Particularly notable to followers of collegiate rivalries, Vosper’s design and teaching careers spanned years on the faculties and staffs of both Texas A&M and the University of Texas. Although his formal education included only three years at the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, he made his name as a highly successful architectural designer by apprenticing during the day as an architectural draftsman in New York City and studying Beaux Arts design by night in an atelier or studio.

Embracing the Beaux Arts Tradition

In the first decade of the twentieth century a Beaux Arts education was highly prized in architecture. Students of means studied in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and many returned to New York City to teach in the nation’s epicenter of Beaux Arts activity. Vosper took full advantage of this classical architectural education as well as additional classes in oil painting, life drawing, theater design at the Metropolitan Opera House, and architectural rendering with a Frank Lloyd Wright mentor. The popularity of Beaux Arts architectural design would continue into the fourth decade of the twentieth century.

Bringing his Art to Texas

Finding his way to Texas via his work with a theater company, Vosper spent his next three decades in the Lone Star State — starting out in Dallas, then moving to San Antonio, where he designed the landmark Scottish Rite Cathedral. Shortly, he began teaching at the University of Texas in Austin and eventually was hired away by Texas A&M.

Dipping into the newly-acquired Permanent University Fund obtained from the Permian Basin oil discovery, Texas A&M launched a building boom. Vosper saw an excellent chance to employ his Beaux Arts training in the planning and design of 10 new buildings to accommodate university administration, chemistry, animal industries, a library complex, a horse barn, agricultural engineering, a veterinary hospital, two residence halls, and combined petroleum engineering, geology and engineering experiment station facilities.

Images to Delight the Senses

Highly expressive of the agricultural and mechanical origins of Texas A&M, Vosper’s Neoclassical buildings delight the senses with uncommon color, sculpture and ever-present wit borne of the early 20th century Beaux Arts style of architecture. Dramatic columns, sweeping staircases and expressive bas-relief sculpture characterizing animals, plants, human faces and forms adorn the structures.

Even the arrangement of floors in a multi-story building is established in Beaux Arts design through adherence to symmetry, axis, scale and the choice of column order. Architectural ornaments are artfully linked to images such as seashells or animal faces to express the building’s purpose. And, while Vosper used a limited palette of materials, he was able to employ the creativity of artists he had come to know in Austin and San Antonio. In the full glory of their original finishes, viewers today enjoy the cast plaster, marble, Mexican cement tile, terrazzo, stained and leaded glass, carved wooden doors and cabinetry, and ornamental ironwork so characteristic of the luxurious era.

“Architecture That Speaks,” $40 cloth-bound, 224 pages, 158 color photos, 52 black and white photos, 28 line drawings, is available from Texas A&M University Press, 800-826-8911. It is also available in an e-book version and at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other nationwide bookstores.

About the Authors

Nancy McCoy is an award-winning preservation architect with more than 25 years of national experience, a member of the American Institute of Architects’ College of Fellows and an Outstanding Alumna of the College of Architecture.

Her projects include the historic Texas A&M YMCA building, 30 conservation projects in Fair Park in Dallas, including the expansion of the Cotton Bowl, the Martin Luther King and Grand Avenue Entrance gates, the restoration of the Parry Avenue entrance gate and the Esplanade Fountain, the intricate conservation of historic murals and the restoration of several buildings.

Her work, among her numerous other conservation projects across the nation, has earned 30 preservation design project honors, including two National Trust for Historic Preservation awards.

David Woodcock, also director emeritus of the Texas A&M Center for Heritage Conservation and an AIA Fellow, educated generations of preservation professionals during his 49 years on the Texas A&M architecture faculty.

“It is nearly impossible to go to a preservation meeting and not run into someone who hasn’t either been taught by him directly or been influenced by him,” said Bob Warden, interim head of the Texas A&M Department of Architecture.

Woodcock, who retired from Texas A&M in 2011, established and directed the Historic Resources Imaging Lab at the Texas A&M College of Architecture in 1991, which later became the CHC. The center’s mission is to train students, professionals and others in the use and application of imaging processes relative to historic and cultural resources, to develop new techniques for documentation, analysis, visualization and interpretation, and to apply imaging techniques to the study of historic resources.

He also created and developed the College of Architecture’s Certificate in Historic Preservation, a program of courses integrated within a wide range of professional disciplines. The certificate, which has gained wide acclaim and serves as a model for other programs, is awarded each semester to Texas A&M graduates from diverse disciplines.

This story originally appeared on the College of Architecture website.

###

Media contact: Richard Nira, Communications Specialist, College of Architecture, 979-458-0442, or rnira@tamu.edu; or Elena Watts, Division of Marketing & Communications, 979-458-8412 or elenaw@tamu.edu.