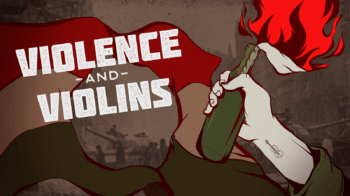

Violence And Violins: Prof Recalls His Role In The Hungarian Revolution

In late October 1956, Joseph Nagyvary found himself smack in the middle of the Hungarian Revolution as a 22-year-old student at the University of Budapest. The future Texas A&M University professor was using his chemistry skills in an unlikely way – making Molotov cocktails to throw at Russian tanks, and he literally did not know if he would live from one day to the next.

In late October 1956, Joseph Nagyvary found himself smack in the middle of the Hungarian Revolution as a 22-year-old student at the University of Budapest. The future Texas A&M University professor was using his chemistry skills in an unlikely way – making Molotov cocktails to throw at Russian tanks, and he literally did not know if he would live from one day to the next.

Today, as the 60th anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution approaches, the 82-year-old Nagyvary has written his recollections of those days in his new book, Violence and Violins, an engrossing account of his life under a dictatorship.

Things peaked in November of 1956 when Russian tanks rolled into town and began killing hundreds of the student-led revolutionaries called “Freedom Fighters.” Due to some lucky coincidences Nagyvary survived, and eventually made his way to the United States and the Texas A&M campus, where he taught for almost 40 years before retiring a few years ago.

“I was an eyewitness to history and also a participant,” Nagyvary explains.

“It was a terrible, awful time. The Soviet commanders and their Hungarian henchmen were absolutely ruthless – if they thought you were even remotely involved in the revolution, they would execute you on the spot.”

The problems in Hungary had started on Oct. 23 when thousands of protesters led by college students demanded a more democratic political system and less oppression from Soviet rule, plus economic reforms. Russian tanks soon cruised through Budapest to put down the revolt and within days at least 2,500 Hungarians had died in the ensuing battles.

“The fighting was contagious,” Nagyvary recalls.

“The shooting and throwing of Molotov cocktails was started by working class teenagers, but soon we were drawn into the battle against our better judgment. I could not resist joining them.”

Nagyvary himself and several friends were soon captured by the Communist State Police (AVO) in a dormitory. “The AVO officer told us they would search the place, and if any weapons were found, we would be shot immediately. I knew there was a secret door downstairs and managed to escape. In a similar situation a few days earlier, two of my good friends were killed.”

Sporadic fighting continued throughout November, and the Hungarians were upset that the U.S. would not come to their aid.

“It was November and right during the presidential election, and President Eisenhower and (secretary of state) John Foster Dulles announced they were sympathetic to our cause, but they did not want to get involved,” he says. “It was a very complex situation. We had few weapons and were no match for Russian tanks. We all knew it would not end well.”

Within a few weeks, the revolution was over and Soviet order had been restored. Hungarian Prime Minister Imre Nagy was captured and executed two years later. Over 200,000 Hungarians broke through the Iron Curtain and fled to the West, and Nagyvary also managed to escape to Switzerland where he finished his studies, and then came to the U.S. in 1964 and settled at Texas A&M.

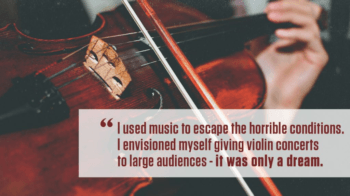

He says his love for music and the violin helped to keep him sane and alive during the years of Communist terror. “My own brother became a Communist and his loyalties were suspect,” he adds. “We were constantly worried that he would turn us in.”

He says his love for music and the violin helped to keep him sane and alive during the years of Communist terror. “My own brother became a Communist and his loyalties were suspect,” he adds. “We were constantly worried that he would turn us in.”

“I used music to escape the horrible conditions. I envisioned myself giving violin concerts to large audiences – it was only a dream,” he recalls. Soon after his arrival in Zurich, the opportunity arose for him to learn the violin by using an instrument that once belonged to Albert Einstein.

One aspect of his dream that was real world was his curiosity about Stradivarius, who made the most-sought musical instruments in history – and the most expensive ones, some of which today are valued around $16 million each.

Nagyvary had always wondered how Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737), who had little education and no scientific training, could have produced musical instruments with such unequaled sound. He researched the era and found that a worm infestation in Italy 400 years ago swept the country and people were treating wood with chemicals to protect it, with borax being the primary agent. In 1976, Nagyvary proposed his theory that the chemicals used to treat the wood – not Stradivarius’ violin-making skills – were responsible for its unique, pristine sound.

His theory caused considerable outrage in music circles, but several years later the American Chemical Society, the world’s largest scientific organization, did its own tests and concluded that Nagyvary’s work was indeed correct. He has since won numerous awards for his work and his research is cited in numerous high school and college chemistry textbooks. Though retired, he is still asked to speak at music festivals and conferences, such as the one in Tokyo in 2005 that marked the 50th anniversary of Einstein’s death when Nagyvary spoke about his violin research.

“I am often asked why I wrote my book, which was almost 10 years in the making,” Nagyvary says.

“One reason is for the benefit of the youth of America, which has the largest stake in our future. Preserving our freedom and Constitution requires alertness to many dangers, and it demands actions on our part. One has to be alert to the pervasive pressures to undermine our cultural and moral values. The preservation of freedom may require sacrifices.”

Media contacts: tamunews@tamu.edu.