Sea Grant Projects Improving Flood-Control, Water Quality In Houston Area

Volunteers and staff from the Texas Coastal Watershed Program (TCWP) and Clear Lake City’s Exploration Green Conservancy raced an oncoming storm earlier this summer and saw first-hand the effectiveness of their work to help manage floodwaters and improve water quality in the Galveston Bay watershed.

TCWP, a partnership of the Texas Sea Grant College Program at Texas A&M University and Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, is collaborating with the Clear Lake City Water Authority on the Exploration Green project. Mary Carol Edwards, TCWP’s Stormwater Wetland Program Coordinator, is leading the effort to convert a golf course into a 200-acre green space dedicated to conservation, recreation and flood control. When complete, the project will include about 40 acres of stormwater wetlands — wetlands that are installed in stormwater detention basins. The basins are designed for flood and sediment control, but the addition of wetland plants improves water quality and flood control and increases recreational opportunities and habitat for wildlife.

“Our drainage systems are set up to just send water downstream. However, when it is just as flooded downstream, the water simply spreads out into the area. Stormwater wetlands help to change this process by retaining water properly, purifying it, allowing it to be habitat enhancing, and then allowing it to go gradually downstream,” Edwards said.

“The Exploration Green project will naturally filter and clean the rainwater as it flows through the detention ponds and into Horsepen Bayou, Clear Lake and Galveston Bay.”

Wetlands clean water in a variety of ways — the plants directly filter sediments out of the water, while the biochemistry of the wetlands transforms pollutants into less harmful forms, and many pathogens are consumed by microbes or disinfected by solar radiation. Wetlands can also help cut down on pests that are often found in standing water like detention basins. “Stormwater wetlands are a natural habitat for mosquito-eating dragonflies and fishes that help to reduce mosquitoes in the area,” Edwards said.

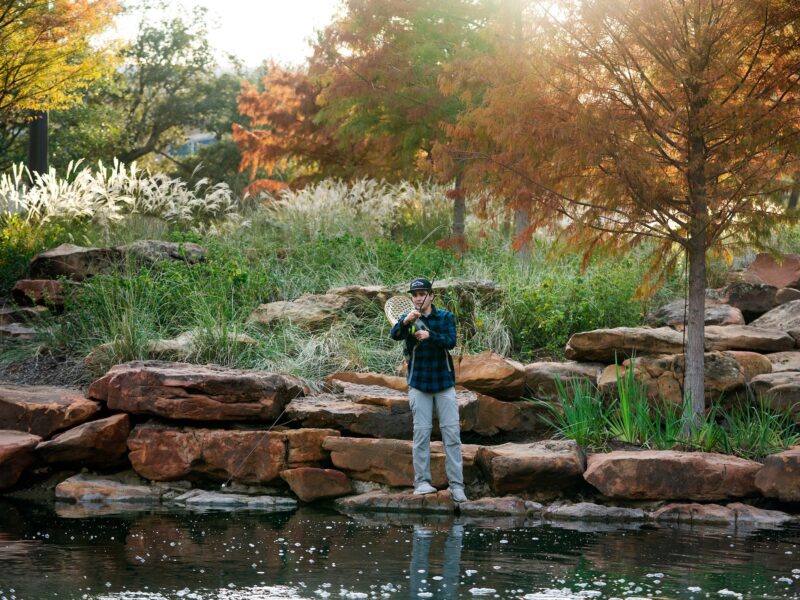

On a Saturday in late June, more than 20 volunteers joined TCWP and Exploration Green staff for a community wetland planting day to install the first half-acre of the stormwater wetlands. They were able to get about three-quarters of the area planted before a short, powerful, fast-moving storm hit. As everyone took shelter, they were able to see the new design of the detention basins working as planned, as water rose only into the areas they had just planted.

TCWP’s stormwater wetlands projects rely heavily on volunteers for planting and maintenance. Doug Peterson, vice chair of the Exploration Green Conservancy, said that though these projects are funded, volunteers’ contributions speed up the process and allow more work to be done.

“Volunteers are essential to projects like turning a golf course into a new natural area that wasn’t here before,” he said. “It’s not always in the budget to pay for these to be done quickly, but volunteers like those who came out here to Clear Lake help to make that difference.”

Anna Armitage, who lives close to the planting site at Clear Lake, brought her son Zac Chan, age 6, to help out. Armitage is an associate professor in the Department of Marine Biology at Texas A&M University at Galveston, where she studies coastal and wetland community ecology. She said stormwater wetlands like the one at Clear Lake are important not only for flood control, but also add recreational value and a unique opportunity for neighborhood residents to be close to nature.

“This will give our children a green area to explore and learn about the plants and animals that frequent the wetlands, right in their own backyard,” she said. “It makes my son and I feel great to help with a project that benefits our neighborhood, and I’ve enjoyed the sense of community as we work side-by-side with our neighbors. I hope others will join us here and in future phases of Exploration Green wetland planting.”

The first-hand view of the results of the project was of special interest to one of the volunteers. Md Yousuf Reja is a Texas A&M graduate student in urban planning interning at TCWP whose studies focus on flood mitigation and stormwater wetlands. He said he was excited to be taking part in the planting both because of his degree and because his mother has always stressed how important it is to volunteer and help his community.

“This is a great chance I’m getting to help build a stormwater wetland and to see my research put into action. This is my first time getting to come out to one of these sites and help out,” Reja said. “Due to how my mom raised me, I’m always looking for ways to volunteer.”

Edwards also coordinates two wetland plant nurseries, the Exploration Green Conservation and Recreation Area Wetland Plant Nursery and at the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory in Lake Jackson, which combined can hold about 34,000 plants that staff and volunteers plant at stormwater wetlands in the Houston area.

Her other projects include several sites at the 200-acre MD Anderson Cancer Center, where former facilities manager David Renninger began an initiative to convert the complex’s basins into stormwater wetlands. One wetland in the detention basin for a parking lot expansion was recently completed, a second is under way, and two others have been identified for future installations.

A former colleague of Edwards’ put her in contact with an employee from NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) when the center was deciding what to do with a patch of land that continuously held water. JSC first considered making the grounds into a rain garden, but it soon discovered it had too much land and not enough money. Although it was not a stormwater wetland, Edwards intervened and helped identify local wetland plants already on-site, helping the area become a true wetland. JSC has discussed adding a weir, a small dam with holes over the outflow area, to help the water drain gradually and give the wetland more time to clean the water.

In stormwater detention basins where the water level is too deep or fluctuating, or where the edges are too steep for a typical in-ground wetland, TCWP works with partners to install floating wetland islands, man-made rafts that float on the water’s surface and house native wetland plants. Edwards has two such projects under way. At Pearland’s John Hargrove Environmental Center, floating wetlands have been placed at the mouth of a 26-acre detention pond, and wetlands are also being established along its perimeter. She also led the installation at the Clear Creek Independent School District’s Education Village Floating Wetlands and is managing ongoing improvements in the wetlands and floating wetlands of the 6-acre pond on campus, which is also used as an outdoor classroom. Another round of planting will start there in October.

Edwards also oversees the Wetland Economic Benefits for Landowners website, an online clearinghouse of programs that provide economic benefits to private landowners for wetland conservation.

Media contact: Tiffany Evans, Texas Sea Grant.