TRAILBLAZERS: June Scobee ’83

It’s not an exaggeration: Aggies are everywhere. And some use their education and experience to generate an awe-inspiring maroon ripple effect. These stories are about people whose impact extends beyond Texas A&M University. With courage as a compass, the paths they have forged multiply into the distance. And the limits of their determination are yet to be seen.

These are the trailblazers.

As June Scobee ‘83 sat on the ivory sofa in the living room of her Chattanooga townhome, she draped a gold chain across her neck.

“I just returned from the gym,” she apologized. “I had time to shower and dress, but I still need to put on my necklace.”

Apart from her diploma and a large pine bookcase she purchased in Spring, Texas, Scobee’s home bears little indication of her Lone Star State connection. She’s not situated on acres of ranchland nor does she festoon her walls with Texas stars or A&M pennants. But the petite 73-year-old has a rich Texas history, one that took her from San Antonio to the Johnson Space Center to Aggieland.

Although she was born in Alabama, if you ask where she is from, her response is adamant: “I’m from Texas. Period.”

“Everyone who works with my bio always wants to put that I’m from Alabama, but I only spent two years of my life there,” she added.

Much like the subject of her home state, many other aspects of Scobee’s life are composed of blurred boundaries. Her time of destitution bled into her success. Her commitment to faith comingles with her passion for science. Her private life abuts her very public persona. And one of her life’s greatest tragedies—the loss of her first husband—dovetails with some of her most significant accomplishments.

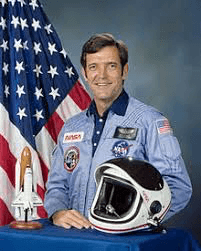

She is the widow of Dick Scobee, commander of the Space Shuttle Challenger, which exploded 73 seconds after takeoff on Jan. 28, 1986.

Stars in Her Eyes

As a child, Scobee (then June Kent) would gaze into the night sky and name the constellations. She’d often wish on stars, praying to God as she marveled at the vastness of the universe.

Her family life was tumultuous—her parents struggled financially, and their marriage ultimately failed as a result of her mother’s ongoing battle with schizophrenia. The eldest of four children, Scobee was thrust into the role of caregiver for her siblings, adapting to a frequently changing environment while striving to be a rock for her family.

These experiences no doubt shaped her into the woman she is today—tender and affectionate (she signs her emails “with oh so much love”), but also feisty and resilient.

Guided by two books—the Bible and Norman Vincent Peale’s “The Power of Positive Thinking”—as a child, Scobee created her own version of the ABCs as a device to get through her tough periods. A stood for attitude, B for belief and C for courage. “I lived by those words,” she said. “And as I lived them, positive things started happening for me.”

Perhaps the start of those “positive things” was her introduction to Dick Scobee, a high school boy with a letterman jacket and sky-high aspirations. The pair met in San Antonio when she was 16 and married shortly thereafter. “We saved each other,” she said.

Their family expanded as the Scobees welcomed first a daughter, Kathie, and then a son, Rich. The couple worked to earn their college degrees (both started at San Antonio Community College, but she completed her undergraduate education at Charleston Southern University), and while Dick Scobee pursued his dream of becoming a pilot, his wife’s teaching career took off.

“I wasn’t going to be a great scientist or an attorney,” said Scobee, “but I knew I could touch the future with these youngsters, that I could inspire them to go into these fields and be the best they could be.” She would go on to teach all grade levels and nearly all subject areas.

When Dick Scobee was selected as an astronaut for NASA, the family moved from California—where he attended the Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base—to Houston’s Johnson Space Center. The relocation gave Scobee the opportunity to start graduate school. Each week, she made the 120-mile journey to College Station to earn a doctorate in curriculum and instruction from Texas A&M University’s College of Education and Human Development.

“That was a tough time,” she said, reminiscing on the early ’80s when she was attempting to bolster her own career while still supporting a family. “I was ready to quit, when my teenage son and daughter gave me this little plaque that said ‘Dr. June Scobee’ and said, ‘You’re going to disappoint us if you don’t finish your degree.’”

Her family’s “permission to finish” was a game-changer. Many years later, she realized that this time apart from her children allowed them to spend precious time with their father. “I kept worrying about being away from my family, but in retrospect, after my husband died, I realized it gave them a chance to be with him more,” she said. “My daughter learned how to cook for them. My son went out flying airplanes with him.”

While at Texas A&M, Scobee would teach school and attend classes in the same semester, and she found great support in her faculty advisers, particularly William Nash, now a professor emeritus in the Department of Educational Psychology. With Nash’s guidance, she helped develop a space science program through the Texas A&M Gifted and Talented Institute. The institute gave gifted teenagers a glimpse at career possibilities through hands-on experiences. Scobee remained active in the program even after she completed her studies.

“June wanted to create every opportunity she could for young people to learn about space science,” said Nash. “She has a strong sense of curiosity and courage in her convictions.” And while many people, unsettled by the unknown, “rush to produce commonplace ideas,” Nash explained, “Scobee had great toleration of ambiguity.” She patiently waited for eureka moments to arrive.

Scobee views this snapshot of her life from a larger perspective. Her graduate school experience, she believes, “gave me the confidence to talk about turning the tragedy of the Challenger disaster into something positive.”

In 1983, Scobee graduated just one year before her husband flew in space for the first time. Following the successful mission, NASA selected Dick Scobee as commander of the Challenger flight, later dubbed the Teacher in Space Project. June Scobee would spend the following months getting to know the crewmembers and their families, and her passion for education inspired a close alliance with Christa McAuliffe, the New Hampshire teacher chosen to conduct lessons from zero gravity.

“From her arrival in Houston, June took Christa under her wing, making sure she came for home-cooked meals, and they’d just hang around and talk,” said Steve McAuliffe, Christa’s husband.

Much like Scobee’s own teaching model, McAuliffe’s plans involved hands-on lessons for schoolchildren to conduct back on earth, including experiments about Newton’s laws and hydroponics.

But Christa McAuliffe never demonstrated projectile motion or how to grow mung beans in space.

On that bitterly cold January morning in Cape Canaveral, Florida, Scobee and her children stood with Steve McAuliffe and his two children, explaining to them what was happening as the shuttle prepared to launch. Then, as the twin rockets hurtled into space, everything changed. To the world’s horror, the O-rings that sealed the joints of the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters failed, causing the shuttle to burst into a ball of smoke and plummet into the sea.

A Eureka Moment

The loss of her husband and the six other crewmembers left Scobee reeling. But, “I felt responsible for the families, and continued to be the mother hen of the group,” she said, remembering her ABCs to find the courage to help others while mourning her own deep loss. “We wanted the world to remember not how they died, but how they lived and what they were passionate about.”

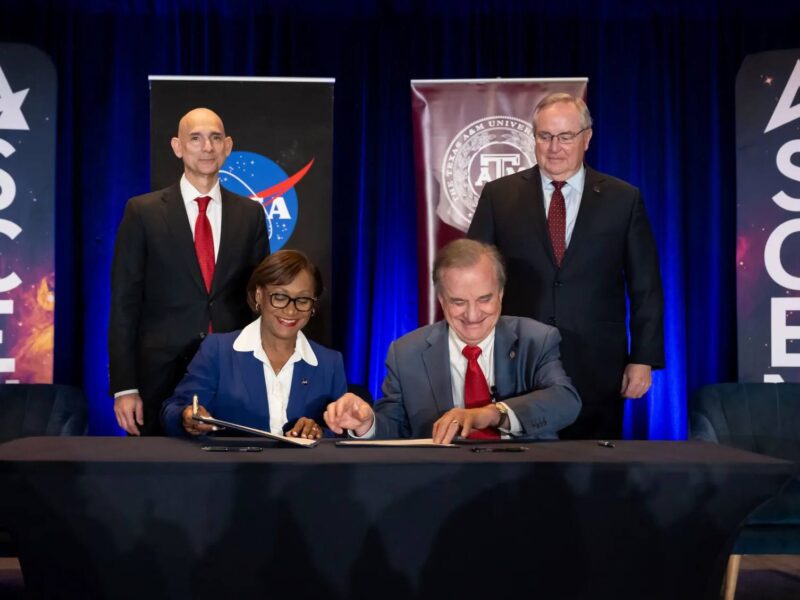

Recalling the space science program she directed through Texas A&M, Scobee worked with the families to set up the Challenger Center for Space Science Education to continue the crew’s educational mission. She confided in then Vice President George H.W. Bush about the project. Bush encouraged Scobee to expand the Challenger Center’s board of directors to include national representation, advising her to treat the experience as a day in front of class.

“He said, ‘Believe me, they’ll listen to you if you paint a vision for them of where you want this to go and what you want it to be. All you need are your teaching skills.’” And he was right.

Today, the organization operates nearly 50 Challenger Learning Centers in the U.S., Canada, South Korea and the U.K. The program reaches more than 500,000 students annually, offering interactive activities like simulated missions to Mars or the moon in a classroom-sized mission control.

Scobee speaks to groups around the country about the importance of STEM education and taking risks in the name of discovery. She remains on the board of the Challenger Center, serving as its founding chairman. In 2011, she was named an outstanding alumnus by Texas A&M. She also wrote the book, “Silver Linings: My Life Before and After Challenger 7.”

Dick Scobee and the Space Shuttle Challenger will always be an inalienable part of her identity, but Scobee has built a new life for herself. She has been remarried to retired Army Lt. Gen. Don Rodgers for more than 25 years (she now goes by June Scobee Rodgers). Together the couple has nine grandchildren.

“He’s the sweetest man,” Scobee said of Rodgers as she touched two intertwined hearts on her necklace.

“It was a golden anniversary present to celebrate 50 years of marriage—25-plus years to Dick and 25 years to Don,” she said with a smile. “It stands for both my loves.”

It’s the perfect symbol for the many intersections of Scobee’s life: All of the links fitting together in their own way, all playing a part of the woman she is today.

The Mission Continues

The year of his death, friends of Dick Scobee set up a memorial scholarship in his honor in the College of Education and Human Development. Scobee had been a member of the college’s development council, and on his first mission in space, he carried a medallion from the college. Scobee provided encouragement to Texas A&M students, even arranging a special tour of the Johnson Space Center. The Francis R. “Dick” Scobee Memorial Scholarship, created through the Texas A&M Foundation, supports students committed to teaching math or science. The college is actively seeking to grow the endowment and support more students who aspire to teach in STEM fields. This effort coincides with the 30th anniversary of the Challenger accident.

To give to the Francis R. “Dick” Scobee Memorial Scholarship fund, visit give.am/SupportScobee.

To locate a Challenger Center near you, visit give.am/ChallengerCenters.

This article by Monika Blackwell originally appeared in the Texas A&M Foundation SPIRIT magazine.