Texas A&M’s Colonias Program Transforms Border Communities

The unique and inexpensive water filtration system utilized at Texas A&M and showcased this summer at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. exemplified one small, but profoundly impactful way that the university is fulfilling its land grant mission in the colonias — impoverished communities in the Texas borderland where more than half a million people live without running water.

The unique and inexpensive water filtration system utilized at Texas A&M and showcased this summer at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. exemplified one small, but profoundly impactful way that the university is fulfilling its land grant mission in the colonias — impoverished communities in the Texas borderland where more than half a million people live without running water.

For more than two decades, the Colonias Program, overseen by the Texas A&M College of Architecture, has been implementing sustainable solutions aimed at transforming these communities, reducing their isolation and helping their residents become full participants in the U.S. economy and society.

There are currently 2,333 colonias in the United States, mostly located along the 1,434-mile Texas border in 14 counties contiguous to the Rio Grande River, said Oscar Munoz, Colonias Program director.

Though characteristics of these small, rural, unincorporated communities vary, they all generally lack one or more of the physical infrastructure amenities most take for granted: running water, sewer systems, paved roads and storm drainage.

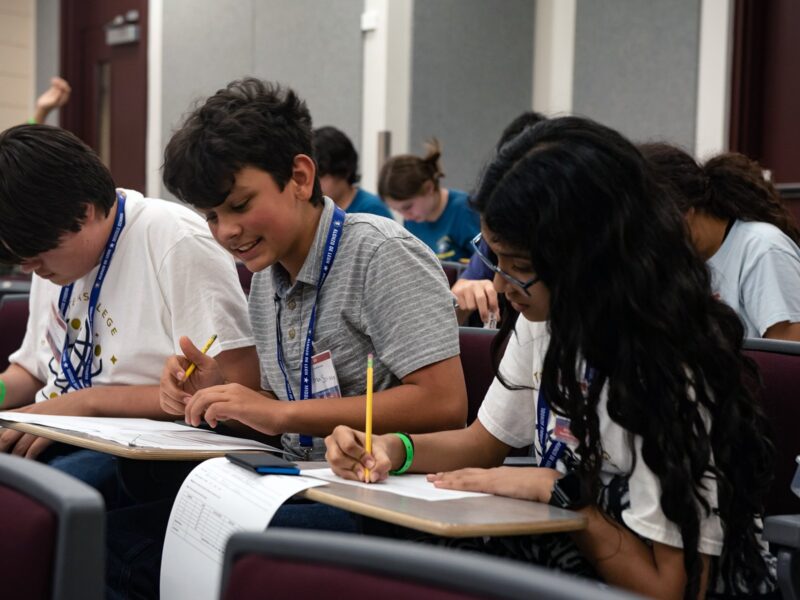

Because of their remote locations, poor economic conditions and cultural segregation, colonias residents tend to be isolated from government services and the various social safety nets that provide education, job training and placement, health care, and programs for the young and elderly.

The Texas Legislature recognized this problem in 1991, establishing the Colonias Program and asking the College of Architecture at Texas A&M to oversee it. In the ensuing 20 years, the program, aimed at catalyzing community self-development, has grown to include 22 community resource centers and 18 service centers, with five new centers in the works, said Munoz.

From the beginning, the program has worked closely with and relied upon the colonias residents themselves. It has orchestrated a wide range of programs aimed at involving neighbors in activities that help them become connected to the larger community outside of the colonia, while strengthening the social infrastructure within.

“In short,” said Munoz, “the Colonias Program gives residents a hand up — not a handout.”

Aiming to reduce isolation, increase self-sufficiency and enhance the quality of life in these communities, the Colonias Program has also partnered with more than 400 agencies to provide educational services, GED instruction, economic and community development assistance, and programs addressing literacy, job training, dropout prevention, job referral, health education, youth and the elderly.

Many of these services are provided at the program’s community centers, tailored to meet the unique needs of each service area. Made possible by partnerships with local entities and mostly operated by county governments or local school districts, they provide classrooms, libraries, medical examination rooms, auditoriums and fully equipped playgrounds. The centers offer colonia residents a place to exchange information, identify problems and develop solutions while serving as a platform for the delivery of a wide range of services and as a community hub and meeting place.

Additionally, aided by a partnership between the program and the Texas Transportation Institute, many of the community centers provide a fleet of vans to assist colonia residents in need of transportation for such things as health care, employment services and day care.

Connecting the colonia residents with available services are more than 80 promotoras, the outreach arm of the Colonias Program. These neighborhood advocates undergo a six-month training program certified by the Texas Department of State Health Services that sharpens their skills in interpersonal communications, capacity building, service coordination, advocacy, organization and teaching. Because they are also colonia residents, they have a unique ability to quickly gain the trust of their client neighbors and connect them with services aimed at elevating their condition.

In Starr County, for example, a team of 22 promotoras accompanied by three supervisors and five van drivers made 3200 home visits to colonia residents during a two-month period, recounted a former program director. From that effort, he said, the local Texas Workforce Commission, which provides workforce development services to job seekers and employers, reported receiving 800 new clients.

“We attract, nurture and develop a wide base of talented men and women and unleash them to respond, impact and transform,” said Jorge Vanegas, dean of the Texas A&M College of Architecture.

“Thanks to their hard work and the crucial support of more than 400 community partners, for two decades the Colonias Program, through its community self-development initiatives, has made great strides in helping families realize their dreams of self-sufficiency and better lives for their children. What counts now are the next 20 years,” he continued, “but I have unwavering hope that the future we want and need will come.”