A Post Card From Italy

At the arched entry gate of Porta Fiorentino, the stranger asks a passing resident, “Donde Texas A&M?” in her border-state Spanish. The villager speaks only his native Italian, but knows the answer. He points upwards indicating to the visitors that their destination is further up the hill.

Moving up the steep path of autumn-colored stones, their roller suitcases click and clank on the mortar, interrupting Castiglion Fiorentino residents chatting on the narrow car-less main street. Winding higher on the shrinking corso, from tiny courtyards women hang laundry in the morning sun.

The fragrance of clean clothes follows them as they continue to climb. At the very top, they reach a crumbling medieval fortress. Resting, they survey the valleys below. From this same vantage point, medieval sentries also scanned the horizon looking for rival forces from Siena, Arezzo or Pergulia. These nearby Italian city-states regularly invaded the town of Castiglion until an ingenious alliance with Florence, the Renaissance powerhouse, halted the assaults. The addition of Fiorentino to Castiglion heralded this new, prestigious protection to the neighbors.

Allured by the historic view, the two have missed their destination. Downward they return to the municipal piazza where locals are enjoying a late morning caffé under the shade of the loggia still adorned with a Renaissance Medici crest.

“Scusi, dove `e Texas A&M?” She asks a watchful table in passable Italian. The residents smile and gesture in unison to a nearby vicola, a steep short-cut. “Boun giornetta,” they say, wishing them a good journey.

The passage empties at the narrow, double doors of the Texas A&M University Santa Chiara Study Center. Although the building is unmarked, the townspeople know Texas A&M is located in the former convent of the 14th Century Order of Poor Clare’s (Chiara is Claire in Italian).

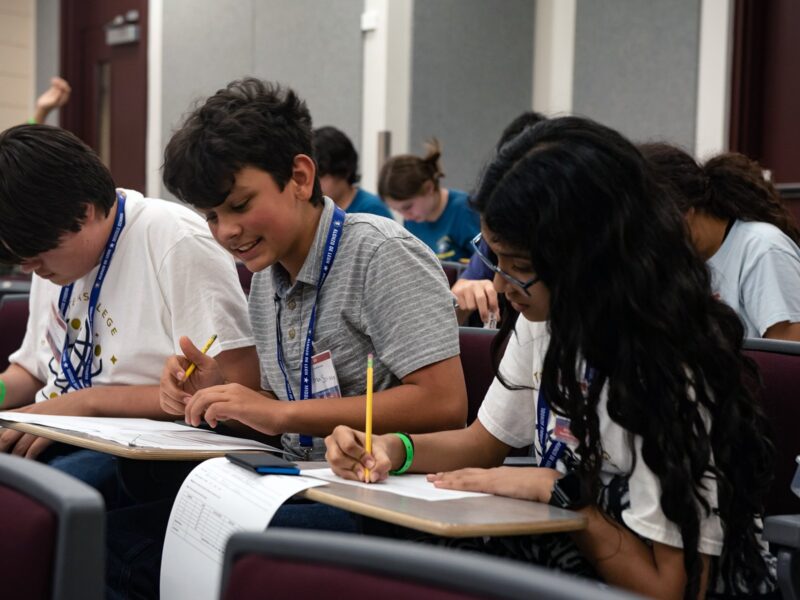

Accompanied by my husband, I am returning to the program I attended in 1982. For more than a quarter of a century Aggies have studied abroad in Italy. Through this program, resident and visiting Texas A&M professors conduct classes in architecture, history and a variety of liberal arts. Other universities including the University of Kansas, the University of Texas and California Polytechnic State University regularly send students and faculty. Students live at the center. Class is Monday through Thursday; field trips are on Fridays and weekends are free for students to travel. Some semesters, there are customized classes. This spring, a group of students from the College of Education taught English as a second language at the local middle school.

It is the first day of the new semester at the Santa Chiara Study Center. Administrator Sharon Jones greets us. Sharon is Santa Chiara’s charming consigliere, the bridge between modern American culture and everyday Italian life.

This new location replaces the isolated original called La Poggerina. Because the train station was several miles away from the “Pogge” we had to hitchhike to a nearby train station to take our weekend trips. With her roadside Mona Lisa half-smile, my childhood friend Laura Lister Stonecipher ’85 became our best hitchhike. She was able to secure rides for us in passing World War II-era family farm vehicles. When the lease at the Pogge expired in 1989, students rode the center’s bus to check out three possible new locations. They selected Santa Chiara in Castiglion Fiorentino, a medieval, walled Tuscan town perched on a hilltop with a conveniently located train station.

Driving here, I have noticed Tuscany is more prosperous now, as evidenced by newer and more plentiful cars; those tiny farm carts are gone. There are numerous American university study abroad programs scattered in these hills, but few have their very own town. The Texas A&M study center is located in rural Castiglion Fiorentino, a place where people live and work, mainly in agriculture. More popular tourist towns – nearby Siena, Cortina and Florence – garner the visitors. The Castiglionesi have maintained their Renaissance reputation for pride and rispetto, respect. To the students living within their walls they are gracious and polite and expect the same in return. “Because of this, Aggies have one particular rule, no whooping in town,” Sharon says.

Under barrel-vaulted arches, lunch is served family style on sturdy wooden tables atop tile floors. A dozen teachers and administrators sit at a head table. About a hundred students from A&M and the other universities are interspersed, getting to know one another. The meal is fresh Tuscan produce and pasta from the valleys below prepared by two local women. Lidia, a classic chef, and Giuliana, a home-style cook, are the Italian moms of Santa Chiara with wooden spoons, smiles and Italian-only greetings for all. Today, the primi course is Giuliana’s bean soup and the secundi is Eggplant Parmesan. The taste of fresh olive oil and vegetables is evident in both. For the dolci, or sweet, Sicilian oranges and Tuscan pears are brought in wet glass bowls.

Afterwards, we join the students outside the building for the first field trip of the semester. I am delighted to see the familiar face of Paolo Barucchieri, the Santa Chiara Study Center Director. Paolo is still the same, engaging students with his blue eyes and gentle replies. The group heads for the town’s hilltop fortress called the Cassero. As we walk, Paolo asks the students to guess the age of the town.

“Five hundred years,” says one. “A little older,” Paolo replies, “about twenty five hundred si.” With this, he captures the students’ attention and he will hold it for the semester.

Paolo is an artist, an art historian and the protector of the A&M Italy program. At the Cassero he shows the students what the medieval architecture and Renaissance history have hidden – a portion of an Etruscan city wall (ca. 4th century B.C.). The Etruscans were the original Italians, pre-dating the Romans. Then the students examine an Etruscan temple under the 12th century church of Saint Angelo, now the Municipal Art Gallery.

There, Paolo explains frescos as the TV shows of their time, communicating the stories of the ancient Christian saints to the people of the Middle Ages. He is a gifted storyteller and throughout the semester he will unstack the layers of history, civilization, culture, art, war, architecture, trade, and religion, and then skillfully reassemble them for the students’ consumption.

In the late afternoon, a weekend travel contingent of students gathers in the main reception room amid hundreds of left-behind travel books. Students flip through pages discussing their upcoming weekend trips. “A Guide to Staying at Monasteries in Italy” looks lonely on the shelf, while “Italy for Dummies” is passed around. The students discuss destinations, companions, accommodations, train schedules, and even what to wear.

One Aggie says her short shorts have already made her feel conspicuous, while a young man from Houston in a maroon T-shirt says his ball cap is “too American.” I don’t think he has considered the logo on his T-shirt.

Yesterday, arriving students overloaded the wireless network and were asked to take it easy today. I see why: in the windowless study area, several are emailing home to confirm their arrival or share impressions. In contrast, as a student, I sat outside in the sun admiring the view. My impressions were recorded in long hand on a post card that would arrive home four weeks later. With time and words restrained, by the time my mom got a mention of our hitchhiking exploits, the summer session was almost over.

The key element, though, does not differ and that is the experience these students will have with Paolo and the other instructors as they venture on weekly field trips. During the outings, they will discuss Botticelli’s Renaissance blockbuster, “The Birth of Venus,” at the Uffizi museum; caress the stone supports of the unfinished cathedral in Siena; and walk the concourse between 4,000 dead at the carefully tended American World War II cemetery outside of Florence. When they return to the classroom, the students will examine the meanings of not just cultural but sometimes intense encounters with Italy.

For many students, it will be the time spent in optional individual study with a local artist, a sculptor, a printmaker, or a painter that will be the most memorable. For others it is slipping outside the walls of Castiglion Fiorentino, jogging past centuries-old churches, golden sunflowers and dusky olive trees. In the architecture studio, it is the discussions not only of Renaissance architecture but what future civilization will look like that students will recall. Able to explore so many layers, students discover a place not available in guidebooks or textbooks.

That evening after dinner, we all gather for a welcome concert by a local band in the center’s private courtyard. For the students it is the first of many evenings that will float by in ancient Mediterranean time, without television or phone calls. When the music finishes at 11 p.m., some students stay in the courtyard talking. Others slip off to the Velvet Underground, a local nightclub, stopping first at CoCo Palm to taste their first hazelnut gelato.

In the morning, from across the piazza, the church bells toll at 7:30 a.m. to remind to the residents of Castiglion Fiorentino that mass will start in a half-hour. We join the sleepy-eyed students in the snack bar for cappuccinos as they check computer printed train departure times for their weekend trips.

Sharon says she wants to show me something before we go. I follow her to a locked door of an adjoined building, the church of Santa Chiara. Inside there are candlesticks, framed paintings, and kneelers all barely visible by the soft sunlight through the open door. Above the door is a balcony used by the nuns housed at Santa Chiara to attend mass in semi-privacy from the townspeople. The former 16th century Roman Catholic Church now belongs to the city of Castiglion Fiorentino. Plans are to renovate it as a library for the study center. Last semester the students of Santa Chiara donated money towards needed structural work in the chapel. Every student contributed, grateful to have been a resident of Castiglion Fiorentino.

Outside, I see the Aggie from Houston. He has ditched the ball cap and T-shirt and somehow acquired new, oversized Italian sunglasses to shield the ever-present sun. By the title of the guidebook in his hand, he is on the way to Rome. “So what do you think?” I ask him.

“I think it will change my life,” he answers.

“Buon giornetta,” I say.

This article by Rebecca Noah Poynter originally appeared in International Focus.