100 Years Of Yell

For yell leaders, hoarseness is a badge. Exhaustion is expected. Being sore just means you’re doing your job — and the job is to lead.

Officially, yell leaders are the face of Aggie athletics, promoting and perpetuating support for A&M’s teams. Since the yell leaders’ start in 1907, their position in front of screaming fans has meant unity for thousands.

Now past 100 years, their job continues to be hallowed. It turns out that yell leaders are a very important part of Texas A&M’s story because they help tell it, shape it and, most important, protect it.

In a way, 100 years isn’t just a celebration of yell leaders’ longevity. In Aggieland, strong tradition isn’t contingent on a timeframe. The running joke is give a good ritual a couple runs and it’ll stick. Do something twice in Aggieland, and it’s a tradition.

Instead, 100 years is about celebrating yell leaders’ history, what they’ve seen and have done for the University in their century, and what the group’s leadership has meant during times of transition or trouble.

There were times in A&M’s history when fear, sadness or change could have caused the Spirit to lose its strength — it never did. Built on the grounds of tradition, the 12th Man is strong, but it helps to have someone to whom the population can look for support.

Each school year a new set of yell leaders is initiated in the group’s rich heritage. Though they have all helped lead the University through could-be landmines, some stories stick out more than others.

A Time Of Change

Mike Marlow ’64 was a senior yell leader when school was integrated, the Corps of Cadets became optional and when the University got a new name. The 1964-65 school year was a big one for the former Texas AMC.

“At the very first of the year, President (James Earl) Rudder called in a handful of student leaders,” Marlow remembered. “He wanted to lay out the vision for the year.”

The University’s trailblazer called for a change in student population. Integration was welcomed by students, Marlow said, but bringing women to campus brought major complaint. It was one of the hardest adjustments for the student body during that time, he said, but A&M made it through, even with the initial one women’s bathroom.

“Then of course, at Thanksgiving, four days before Bonfire, (President John F.) Kennedy was assassinated,” Marlow said.

In the wake of the nation’s loss, there was talk of canceling the football game with the University of Texas, Marlow said. The game went on to be televised, but the corresponding Bonfire was set aside out of respect to the fallen president.

The stack was taken apart log by log, the cut timber set aside for the following year’s use. Back then, Bonfire leadership fell under the role of the yell leaders, from cut to stack to burn. Red Pots didn’t get control until 1974, so Marlow still was one of the few calling orders. The decision to not burn was a hard one, he said, but the 12th Man made it through.

“It was emotional,” he said. “Like the rest of the nation, we were grieving.”

Most Aggies were in the Corps, so “he was our commander in chief.”

No matter what was happening, the Spirit must be passed down, he said — yell practices twice a week. “It was true yell practice. We had to teach the freshmen the yells,” Marlow said. That’s what has kept A&M unique.

Cadets got their training, but there was still a rebellious streak Marlow’s senior year.

“A&M was successful in stealing five mascots,” he said.

Marlow can remember several nights being jolted from sleep by a ringing phone. An angry dean from another university or member of law enforcement wanted their mascot back. It was Marlow’s job to see to the safe return of each.

First there was the Rice Owl made of fiberglass, then a living TCU horned frog — “there were two in a glass case. We thought one died, but it turns out it was stuffed.” A call came at midnight to say that SMU’s pony was being chased around a parking lot. Word came a bit later that Texas Tech’s painted horse was wandering around by the freeway.

“The biggest one was when we got Bevo. There were five police agents questioning me. I didn’t know where it was, but I kept getting calls from the abductors,” Marlow said. “They wanted a vet student to come out and cut the horns off.”

No worries, he said. No mascot was ever injured — except the fiberglass owl. It was pictured in the Houston Post missing its head.

Marlow was thrown in the fountain only once that year for a home game win, but that was all right, he said. The memories he treasures most weren’t created out of success or loss; they were made by being a Fightin’ Texas Aggie yell leader. “It was a little easier to have an influence on students back then,” Marlow said. Most of the student body held membership in the Corps of Cadets. “Communication with the student body was easy, because it was easy to communicate with the Corps.”

Could yell leaders be able to continue the Spirit when change brought a new student body?

1999

The unthinkable happened. At about 2:30 a.m., Nov. 18, 1999, Bonfire collapsed. Five thousand logs disengaged from the structure. Fifty-eight students were on the stack. Twelve were killed. Head yell leader Jeff Bailey ’00 was asleep in his dorm room when the news came. The Corps outfit a floor below him in the dorms was set to work on stack that night. People were going room to room trying to get a headcount of who was missing.

At the very beginning of the building process, the University television station set up cameras so the building process could be watched from dorm rooms. They called it the Bonfire Channel. “I immediately turned on the TV, saw the lights and ran out there,” Bailey said.

What he saw—“It’s hard to put words around it,” he said. “Chaos.” Chaos with incredible leadership, he said. “With the fall of Bonfire, the biggest question was what are we going to do? They looked to us as yell leaders,” Bailey said. “How do we respond to this unbelievable situation?”

Considering what he saw on the field that morning, “the answer was not to do nothing,” he said.

The timeframe between Bonfire and game day seemed to last forever. Yell leaders met time and time again with other student leaders and faculty. Emotions were raw, Bailey said. Meeting the needs of thousands, all in different emotional states, would be difficult, but Texas A&M had to stick together. They wouldn’t be able to make it on their own. Some on campus called for the game to be canceled, saying it didn’t feel right to be competitive or yell. Bailey understood the hesitation, but no yelling, no competition? That didn’t bring Aggies together, Bailey said. That would be doing nothing.

In the end, the game and Midnight Yell became a memorial. “We grabbed on to that responsibility,” Bailey said. “There was never a doubt.”

Bailey started carrying a tape recorder to lay down his thoughts. Bonfire tradition held that as head yell leader, Bailey would have recited The Last Corps Trip at Bonfire. The poem meant even more now, so he memorized it.

To be in that place with so much grief, searching for hope, Bailey said, “getting in front of all those people was the single biggest thing I’ve ever had to do. I will always remember.”

Thousands met with lighted candles at the Bonfire site, not as individuals, but as the 12th Man. The yell leaders marched in with the band, but Bailey could see the candles coming into Kyle Field. About 60,000 people showed up for Midnight Yell, filling the stadium up to the second deck and into The Zone.

“Our job as yell leaders was to step up in that momentum, to bring the student body together,” Bailey said. The goal was to provide an outlet for Aggies to grieve in whatever way the way they needed.

Twelve cannon rounds were fired, The Spirit was sung and Bailey addressed the crowd. He doesn’t remember what he said, outside of the traditional Aggie prose. But a special memorial issue of Texas Aggie recorded some of his words: “We’ve got to remember what Bonfire stood for. What makes it special are the Aggies standing around it. So, as we stand here tonight, I hope we yell louder, sing louder and hold each other stronger than we ever have before.”

Bailey said it was an amazing moment. Hugs, tears and a little bit of healing.

Nine years out and looking back on his year as head yell leader, Bonfire is what stands out most — that and being soaking wet after being thrown into the Fish Pond after every home game win. A&M was on a winning streak during his years as yell leader, and Bailey’s dripping laundry bag proved it. “I can remember sitting there fully spent, barely able to move for the next couple hours,” he said.

But, he said, every yell leader can look back on memories. They all helped to “continue to perpetuate tradition.”

Sometimes time doesn’t matter. Not when it doesn’t change things.

“To keep this great tradition, it’s not just about the yell leaders, it’s about the student body and the 12th Man,” he said. “It’s our job to represent and fight for that every day.”

Back To The Beginning

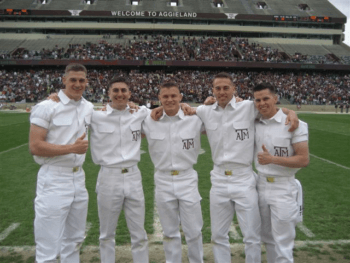

Aggie legend introduces its leading men in an almost slapstick way. The story starts in 1907 at a losing Aggie football game. Back then, A&M was an all-male, cadets-only college — lots of crew cuts, zero ponytails. The arrival of women would eventually come, but at the time, cadets in need of a game-day date would invite women from nearby universities. The railroad served as the shuttle bus of that era.

Aggie lore says that at this particular 1907 football game, the score turned bad enough that a group of ladies from Texas Woman’s University in Denton threatened to leave in boredom. Forget the game, they said. It was time to go home.

Cadets couldn’t have done anything about the game, but they did have command over the underclassmen. The story has never been confirmed, but the tale that has circulated for most of the yell leaders’ 100-plus years is this: With marching orders given by upperclassmen to entertain the ladies, a few freshmen snuck into a maintenance closet and dressed in the janitors’ white coveralls. Coming back to a still dismal crowd and game, the freshmen ran onto the track in front of the stands and started telling jokes and leading the crowd in yells.

A! G! G! I! E! S!

It worked, as legend has it. In fact, the shtick worked a little too well — as soon as the freshmen in white janitor coveralls started getting more attention than the upperclassmen, leading the crowd became an upperclassman-only privilege.

And it still is, as evidenced by the most recent batch of yell leaders.

It’s not an easy job. In fact, since the yell leaders’ inception, there have been only 320 who’ve been asked to complete the task.

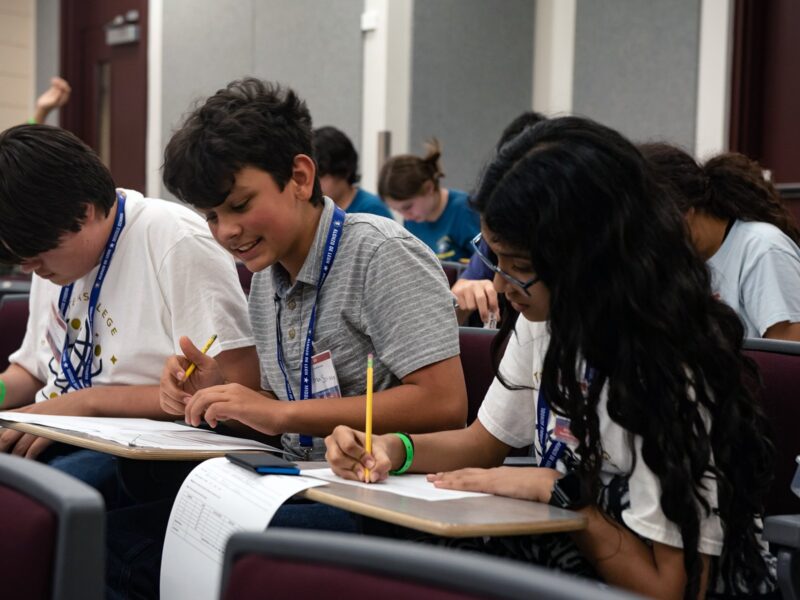

The current five get together with former yell leaders often through The Association of Former Yell Leaders. It’s a much-needed support system for the new boys on the block.

“At the get-togethers, they always offer us advice and won’t hesitate to tell us stories,” Fletcher said.

Right, Wilcox said: “We are the face of the University, and there’s a lot that comes with that.”

They look at their time as yell leaders as a continuance of something good that started long ago.

There’s a difference between tradition and history—history has dates but tradition has heart. Yell leaders serve, Martin said. The history has been recorded, but it’s the continuing heart of the group that makes the yell leaders iconic.

This article by Stephanie Jeter originally appeared in The Texas Aggie magazine.