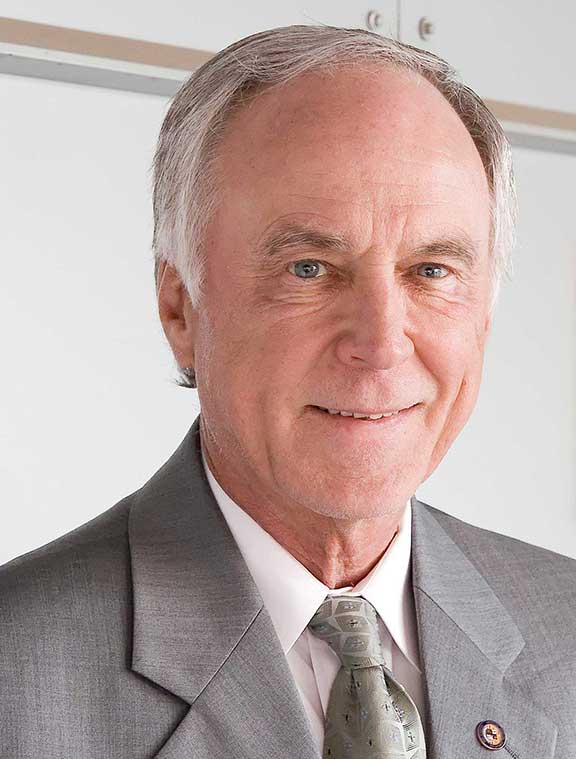

Texas A&M Architecture-for-health Professor George J. Mann has made the most of the vision and good fortune that allowed him to find his calling early in life, and the fruition of more than 50 years of his hard work and influence at Texas A&M University has resulted in generations of significant gains for health care around the world.

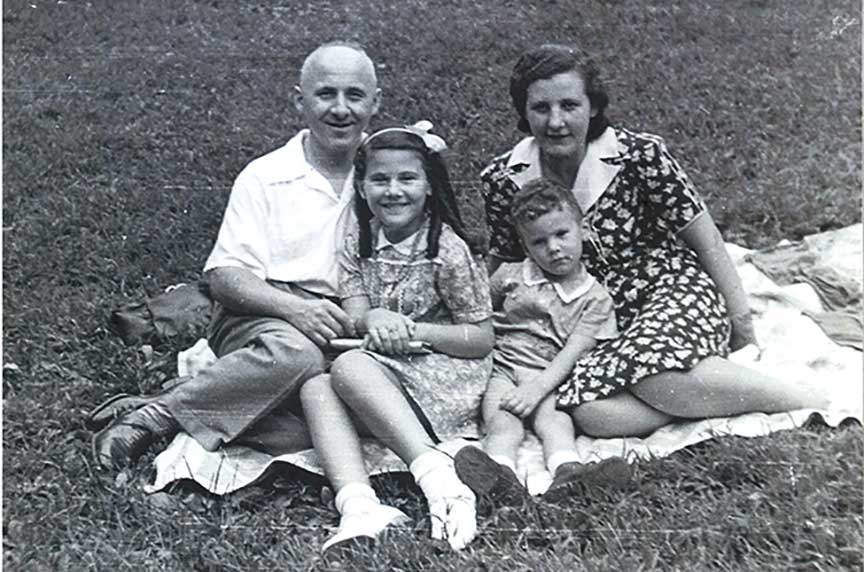

On Dec. 4, 1938, Mann’s Jewish Austrian family fled the Nazis and found refuge in China before finding its way to the United States. Almost 120 members of their immediate and extended family who remained in their homeland did not survive, and Mann credited his parents with saving the lives of his older sister and him through their decisive action.

That was his first fateful encounter with near loss of life that soon met with a second. As an infant living in China with his family, Mann barely survived parasitic dysentery, which made his career of choice, teaching architecture-for-health and designing health care facilities around the globe, especially meaningful.

“Designing health care facilities is my way of giving back, of giving thanks,” said Mann, the Ronald L. Skaggs Endowed Professor in Health Facilities Design in the Texas A&M College of Architecture. “I felt the work was meaningful, it’s still meaningful, and that’s the background, the reason for all of this—we all have our stories.”

In honor of his extraordinary service, the Texas A&M Foundation is endowing the George J. Mann Chair in Healthcare Design. Mann’s former students Ronald Skaggs, chairman emeritus of HKS Architects in Dallas, and Joseph Sprague, senior vice president of health facilities for HKS, pledged the leading donations to establish the faculty chair.

A reluctant traveler

On Sept. 1, 1966, Mann reluctantly traveled from his home state of New York, where he was working as a Columbia University-educated architect, to Texas to meet with his former professor Edward J. Romieniec who had become head of architecture, then a department and now a college, at Texas A&M.

“I’m on Park Avenue, why would I want to come to College Station?” Mann asked his former professor. “Mars is closer.”

Romieniec talked Mann into traveling to College Station for an interview, and then he talked him into a one-year commitment. That one year stretched into more than a half-century during which Mann launched and helped take the architecture-for-health program at Texas A&M to levels of national and international prominence.

“Edward was a father figure who gave me the opportunity of a lifetime by opening doors that allowed me to create this program,” Mann said. “Subsequently, Deans Thomas Regan and Jorge Vanegas have given enormous support to architecture-for-health initiatives, including hiring additional faculty and stressing an interdisciplinary approach.”

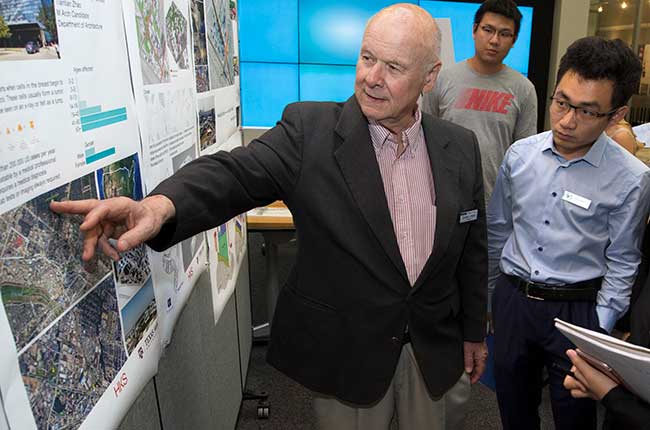

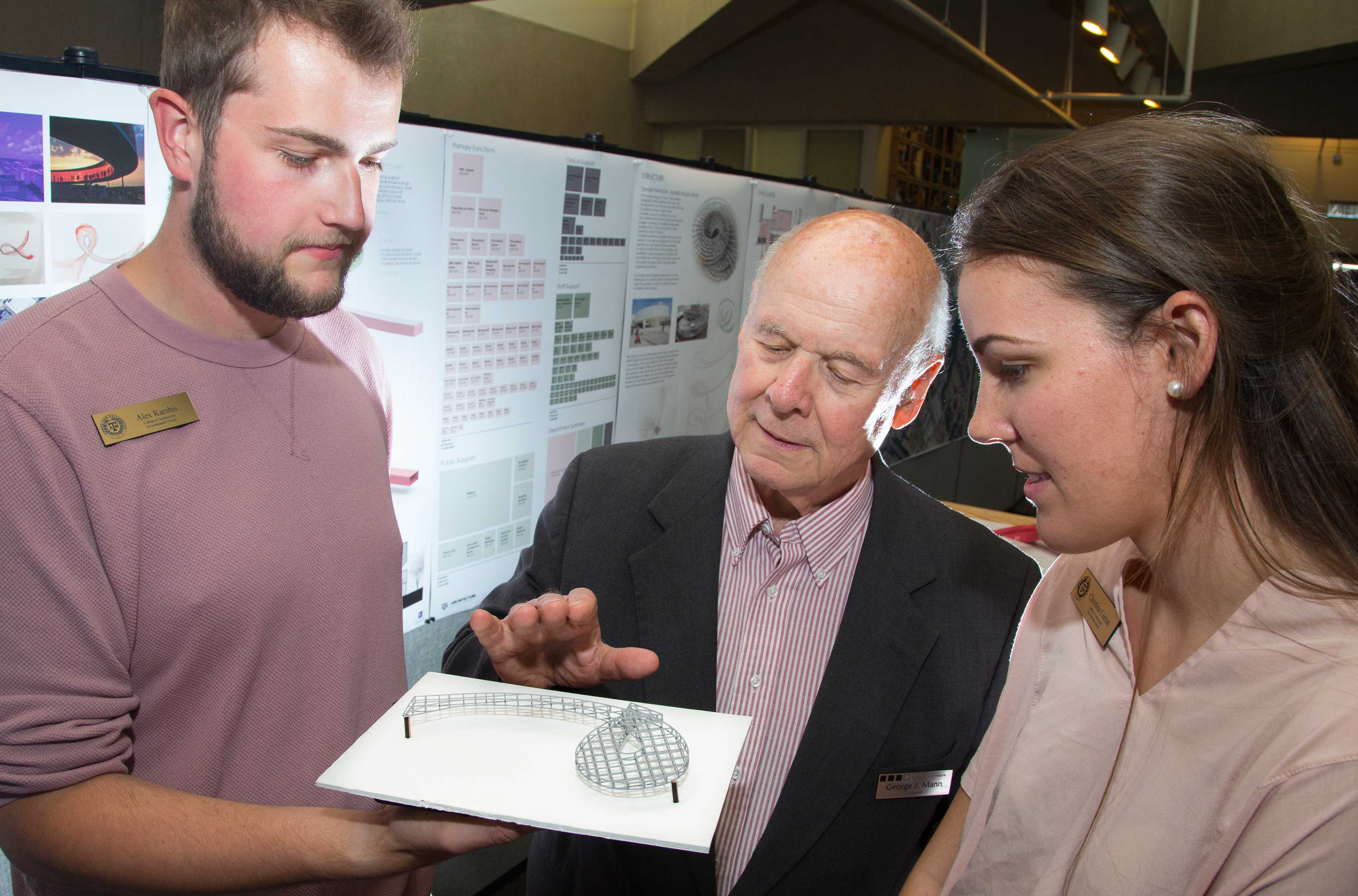

On the shoulders of students

Mann has inspired thousands of students to pursue careers in architecture-for-health, and those former students have become many of the leading professionals in the field, designing thousands of health care facilities worldwide. When Mann acknowledged the tremendous success he has achieved with the Texas A&M program, he quickly added, “I’m really standing on the shoulders of my students.”

“I know successful former students like Ron Skaggs and Joe Sprague, that their careers were influenced, really saturated, by the presence of George Mann, and that they are where they are, in part, because of George,” said Southern Ellis, an associate with HKS Architects in Dallas, who earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture in 2009 and 2011, respectively, from Texas A&M. “Being a mentor for life makes Mann unique.”

Ellis struggled his first couple of years as a student to find a career path that would allow him to reconcile his desire to help people with his passion for design. His junior year, he joined Mann’s health facility design studio, and he knew immediately that he had found his calling.

“George is just a very personable guy who goes beyond being a professor for one semester and mentors a lot of people their entire careers,” Ellis said. “The lasting love George has for his students is incredible.”

Former student John Castorina, national director of healthcare and partner in the Dallas office of Hoefer Wysocki Architecture, also was convinced health care architecture was for him after his first project in Mann’s studio. Between 1978 and 1984, he earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture from Texas A&M.

“George has a way of actually showing that this type of architecture, its responsibility to the general public, is incredibly important, and no one ever stated it that way to me before — how important health care architecture is to the well-being of society, and that as architects, we are actually servants to society,” Castorina said. “You realize that you are a servant to society when the building you are designing is going to render care for people in the most vulnerable state and that you are building things where miracles happen.”

Skaggs, who was a student in Mann’s first class in 1966, chose to change the focus of his specialty from housing to health care design because of his teacher’s influence. The design complexities of the projects, that when completed properly, improve staff efficiency and provide healing environments that nurture and restore patients and their families, impressed him. Skaggs rose through the ranks to become chairman and CEO of HKS Architects, Inc., with headquarters in Dallas.

“George is a very caring human being wishing for every one of his students to succeed. He is a professor who follows his students’ progress after they graduate, and in many cases, he helped get them placed into the firms where they are employed,” Skaggs said. “As a result, the ‘flag’ of Texas A&M healthcare architecture has been carried around the world.”

Since Skaggs joined HKS, the firm has designed more than 1,100 unique projects representing approximately 70,000 beds and 120 million square feet of healing space, and those projects have earned more than 130 design awards.

The “teaching firm” method

Skaggs said that from the beginning, Mann’s teaching style was to involve students in the design of real-life projects, working with health care and landscape architects, medical staff, engineers and contractors.

In 1973, Skaggs and Mann decided to informally create a “teaching firm,” resembling a teaching hospital in medical education, which leverages the symbiotic relationship between education provided at Texas A&M and work conducted by HKS, now consisting of 18 U.S. offices and 6 offices abroad. Since then, Mann’s architecture students have worked on real rather than hypothetical design projects through partnerships with HKS.

Today, there are 11 additional award-winning firms that, as members of the Health Industry Advisory Council, support health care facility research and design at Texas A&M: Bates & Associates, Ballinger, CallisonRTKL, Earl Swensson Associates, Inc., FKP Architects, Inc., HDR Architects, Inc., Page, Stantec, EYP Health, Taiwan Yonglin Healthcare Foundation and Horizon Healthcare Consulting and Management, Inc.

“In my mind, what is most important in George’s teaching is the student’s exposure to real-world problems with an emphasis on careful research of the problem before moving to the solution,” Skaggs said. “There are many other classes where students can learn the design process, but they need this exposure as well.”

The “teaching firm” approach to education has resulted in exposing more than a thousand students to the design of various general and specialty hospitals, ambulatory care facilities and other health-related projects throughout the U.S. and abroad, Skaggs said.

Ellis said that Mann celebrates the team, professional and human aspects of architecture rather than strictly focusing on design and theory. Understanding this holistic approach to design and knowing the language of health care architecture gives Mann’s students a jump-start early in their careers, he said.

“In large part, function rules over form in the design of health care facilities, especially in the U.S., because of the complexity of the codes, rules and parameters,” Ellis said. “But as architects, we know that an incredible design can influence the health of the patient experiencing the space. Access to nature, natural light and beauty can reduce stress in patients and impact the healing process.”

Castorina also learned from Mann that architecture involves more than drawing buildings, though he learned the intricacies of that, too. Mann, he said, emphasizes, “bringing the right people to the table.” He is the “master of connectivity” because he focuses as much on navigating the profession as he does on teaching his craft, Castorina said.

Mann connects his students with professionals while they are still in school; he teaches them how to communicate and how to market themselves; and he encourages them to attend national conventions of health care architects.

“He taught networking more than 30 years ago when no other professor whom I knew did—he was ahead of his time,” Castorina said. “I’ve gotten to travel the world, do all kinds of projects, meet all kinds of people and learn a lot, and I have to give George credit for that, for giving me the knowledge of how to network and work with people, which is a skill I still use today.”

For many years, Castorina has recruited students from schools across the country to work in his architecture firms.

“There’s a great energy and sense of humility from the students at A&M,” he said. “It’s very pronounced, and I don’t mean, ‘Oh I’m not good enough,’ because humility is not thinking less of yourself, it’s thinking of yourself less.”

Healing around the world

From the state-of-the-art design of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston where cancer patients from around the world travel for groundbreaking treatments, to the design and conversion of a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 airplane into a flying eye hospital that delivers otherwise inaccessible care to developing countries, Mann and his students have spent the last 50 years creating innovative spaces for healing. Their health care facilities are located in North America, South America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

Castorina’s first professional project, a 24-story hospital just outside Hong Kong, remains one of his favorite designs after more than 30 years in the business. His latest project is the $480 million second phase of the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. He was lead designer of the $800 million first phase while an employee of CallisonRTKL Architecture.

“This is the only medical institution with five Nobel laureates, so I’m privileged to even work with these guys,” Castorina said. “You deal with the most educated people in the world in this profession, and not only do you have to know your business, you have to understand theirs.”

Being a thought leader in health care architecture means studying all the time to stay abreast of an always-changing medical industry.

“That internal quest for knowledge is essential, and there’s a lot to learn,” Castorina said. “I’ve been doing this for 33 years now, and on a good day, if I know 10 to 15 percent of what’s happening in health care, I feel pretty good about myself – it’s just that vast.”

Designing for different worlds

In the developed world, the focus of health care design is on improving the quality and effectiveness of the facilities, while in undeveloped countries, the focus is simply on providing access to facilities, Ellis said.

“Mann always lectured about the international side of architecture before it was cool, about global banking and connecting internationally,” Ellis said.

Mann connected Ellis with Father Paul Fagan, a Catholic missionary priest, to design a rural hospital in the remote east African village of Nkololo, Tanzania, for his thesis project. Father Paul read about Mann’s work online and contacted him in hopes of securing an architect willing to donate services to his project.

“This project reaches beyond architecture,” Ellis said. “It gets into global, community and public health.”

Ellis traveled to Tanzania to meet with Father Paul and the doctors and nurses who would eventually staff the hospital in Nkololo. Through the fundraising efforts of Roads to Life Tanzania, Inc., a non-profit established by Father Paul, Ellis was able to design and build several buildings, including a surgical suite, an inpatient ward, a laboratory, a mother-child health clinic and an infectious disease clinic, in phases over the last seven years.

“Before, people had to travel an hour on the back of a motorcycle to reach the closest medical facility if an emergency C-section was needed, and lots of times, they didn’t make it there, and they lost the baby,” Ellis said.

The lab facility allows the locals to perform blood transfusions, which helps to combat malaria, one of the biggest health issues in the region. And the infectious disease clinic, which concentrates primarily on AIDS, has attracted an international partner, Doctors With Africa, a non-profit organization that has furnished a full-time Italian doctor who is providing medical, counseling and training services for one year.

“Fundraising is one of the biggest challenges,” Ellis said. “Convincing people on this side of the world that something is very important on the other side of the world is difficult.”

The shortage of medical personnel in the developing world required Ellis and his colleagues to design the facilities in ways that maximize the staff to treat the most number of patients and build housing to attract staff from larger cities to the remote village. They also realized in their deliberations that the construction process could serve as a catalyst for community development.

The team developed a trade school to train locals in construction techniques, such as welding, masonry, carpentry and operation of heavy machinery, which they can use to transform their communities long after the medical buildings are complete, Ellis said.

The substantial phases that remain include another inpatient ward, a private ward and a nursing school for locals that can build sustainability into the staffing process.

Coming full circle

Several years ago, Mann visited the Shanghai office of HKS, which was led at the time by his former student Alex Ling, and Ellis was working there, too. Using a return address that Mann had found on a letter his father had mailed from China to his uncle in Austria many years earlier, the three of them traveled up and down a road trying to locate the apartment where Mann had lived, and nearly died, when he was a child. They eventually found the old building and gained access to a former neighbor’s apartment. The residents remembered the Jewish family that had once lived next door.

“This was one of those moments with Mann outside of the studio,” Ellis said. “His eyes teared up, and it was an awesome moment to share with this incredible mentor in my life.”

###

Media Contact: Elena Watts, marketing and communications specialist, at 979-458-8412 or elenaw@tamu.edu; or Phillip Rollfing, director of architecture communications, at 979-458-0442 or prollfing@arch.tamu.edu.