Texas A&M President, Faculty Share Insight Into 2016 Nobel Prizes

In any given year, dozens of Texas A&M University faculty members nominate individuals and teams for the pinnacle in international academic, cultural and scientific achievement — the Nobel Prize.

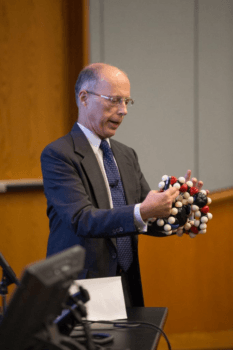

Texas A&M Distinguished Professor of Chemistry John Gladysz opened his Friday (Dec. 2) presentation as part of Texas A&M’s 2016 Nobel Prizes: The Texas A&M Perspective Symposium with this little-known fact, whetting the cerebral appetites of those gathered in the Stephen W. Hawking Auditorium for the first-of-its-kind event and properly setting the stage for piqued curiosity regarding the intellectual work that went into this year’s awards in medicine, physics, chemistry, economics, literature and peace.

Gladysz teased the crowd with a screenshot of an acknowledgement of his most recent nomination, revealing precious little beyond the committee’s trademark logo and letterhead, then eased into his take on the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizing molecular machines and the scientists directly responsible for them.

“When you think about building blocks, atoms and molecules represent the smallest possible units,” Gladysz said. “Whatever you do, the machines must do work. They have to have function. These guys first made building blocks that paved the way for function. It’s happening today in 2016, and it is really exciting chemistry.”

Gladysz was joined by Texas A&M President Michael K. Young and four fellow Texas A&M professors, each of whom explained one of the six Nobel Prizes awarded in 2016: Robert Watson, Assistant Professor of Microbial Pathogenesis and Immunology (Medicine); Eric Rowell, Associate Professor of Mathematics (Physics); Steven Wiggins, Professor of Economics (Economic Sciences); Sally Robinson, Associate Professor of English (Literature); and Young, Professor of Public Policy (Peace).

Watson detailed the merits of award-winning work in Medicine that defined the mechanisms behind autophagy — the process by which all cells get rid of damage and isolate invading pathogens, including tuberculosis, which Watson’s research group works to counteract and accounts for 1.5 million deaths worldwide each year.

“Having an event like today, where all the speakers talk about the Nobel Prize to a general audience, I think is a great thing because it got together all these different areas, number one, and it conveyed to the campus and to this audience why [these] things were important in terms we can understand,” Watson said. “I certainly took away a lot from this. A lot of times you just read it [the research] and don’t understand why that’s significant. Things like this can explain why that is, and it was important to do.”

Rowell familiarized the crowd with math that is fundamental to Physics — namely, topology, the qualitative study of shapes, which he further illustrated with two ropes tied into knots. While the two knots were identical in appearance on the surface, they are deceptively distinct in reality, much like phase transitions in matter that can be topologically detected, which he noted played a role in Texas A&M Distinguished Professor of Physics and Astronomy’s David M. Lee’s own 1996 Nobel Prize in Physics. The applications include next-generation topological quantum computers capable of outperforming typical systems using multi-dimensional braided particles, known in physics as anyons.

“It gives people something to aspire to,” Rowell said of the event. “Young people who might be going into some field can think about the possibility that, ‘I could win a Nobel Prize.’ It’s a very lofty goal, but one that can really propel science forward.”

Gladysz described Chemistry’s molecular machines, focusing on molecular elevators that have a sulfur-based trigger mechanism capable of cycling back and forth between two different electron-dependent versions of the molecule to raise or lower the elevator’s platform, effectively transporting molecular payloads to and from targeted points in the reactionary chain.

“The Nobel Prize is a reflection on excellence, innovation and usually a long career of hard work in one or two areas,” Gladysz said. “Today’s symposium is a chance to reach out, to inform the community of what we think are the important aspects of this year’s Nobel Prizes. I’m a great believer that you need to translate research, translate discoveries, for the public — for the people that support educational enterprises and research enterprises with their tax dollars. I think the community needs more events like this to help keep them informed, to help them understand why research is important.”

Wiggins likewise brought his analogy close to home, tying this year’s prize in Economics — awarded in part for a solution that pays people strictly on outcome when one can’t directly observe effort — to the Texas A&M model in which faculty and staff compensation is based on multiple dimensions observed and otherwise, each somehow related to the university’s land-grant mission of teaching, research and service.

“When I think of the Nobel Prize, I think of all of the effort that gets generated by people who might, or possibly could, win the prize and all of the benefit to society that comes from all of that effort,” Wiggins said. “I think it’s very important for universities to celebrate the advancement of learning, and there is no higher advancement of learning than people who are out there winning Nobel Prizes. I think it’s very important that we acknowledge the great accomplishment of our peers.”

Robinson faced arguably the day’s most difficult task, given the audience’s demographics and likely affinity for Literature’s prize-winning Bob Dylan. She artfully used Dylan’s own words in one of her many analogies, citing his classic The Times, They Are A-Changin’ as a title that foretold a future which would help play a part in “tracking the changing definitions of Literature throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.”

“As I prepared for these remarks, I spent a lot of time reading what smart people who are not literary professionals think about the selection of Dylan,” Robinson said. “I personally know very little about Bob Dylan, cannot easily produce my favorite lyrics and have not studied his work as a scholar. But I know many, many people who treasure Bob Dylan, who see him as the Nobel Prize committee saw him. Although my own interest in this prize has more to do with what it says about current cultural configurations, I have been moved by the testimony of the true Dylan fans, who are legion worldwide.”

Young took to the podium and the task of summing up the event with a caveat, glibly predicting that his talk “will not live up to the lyrics of Bob Dylan, and it certainly won’t live up to the intellectual challenge of the other ones we’ve heard.” He then took the audience through a brief history of time that even the room’s namesake would appreciate, contrasting the 2016 Peace Prize given to Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos for his attempt to end the longest-running conflict in Latin American history — 52 years with 240,000 people killed and more than 6 million displaced — with the award’s inception essentially as a 20-year acknowledgement of Norway’s early and undisputed role in pioneering world peace.

“The Nobel Peace Prize is the only prize actually decided by a Norwegian committee, not a Swedish committee,” Young said. “Norway really was very deeply involved in organized peace movements at the time, about which Alfred Nobel felt very strongly. The notion of advocating peace has been a historically varying concept in the context of the Nobel Peace Prize. Of 19 of the first awards, only two went to people who were not affiliated with the Inter-Parliamentary Union.”

Young noted both world wars changed the recognition model, helping to shift it toward its current mode that rewards global approaches and efforts to resolve specific conflicts while successfully promoting and propelling peace.

“This [year’s] really was an example of a prize that served both as a validation of the effort, as well as a spur to others to recognize, validate and support that effort going forward,” Young said. “It was designed not simply to reward for effort or success, as many of the other awards were designed to do, but to spur additional effort to achieve success in the end.”

The symposium, which was followed by a brief reception, was jointly sponsored by Texas A&M’s Colleges of Liberal Arts, Medicine and Science.

See additional photographs from the event on Flickr.

See a related feature article in the Bryan-College Station Eagle.

Media contact: Shana K. Hutchins, Texas A&M College of Science.