Historic Rains Pound Texas, And More May Be Coming

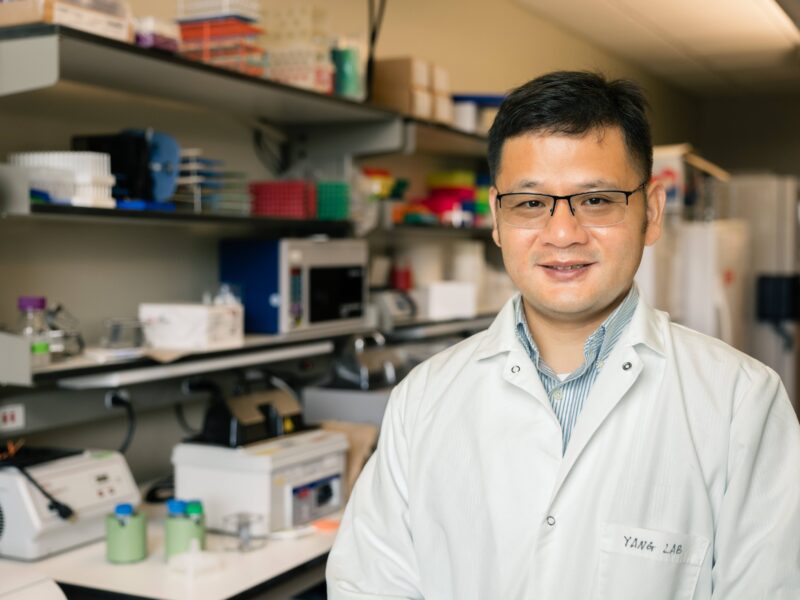

The two flooding events in Texas in late October were record-setters, according to figures and rainfall analyses that go back to 1950. The Oct. 22-26 rainfall event was the wettest storm on record ever in Texas. The average two-day total across Texas was 2.42 inches, shattering the previous record of 2.14 inches set in December 1991, says John Nielsen-Gammon, professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University who also serves as the State Climatologist.

He emphasizes these are overall averages for the state, noting that many localized areas received much higher totals.

Over a five-day period, Texas received an average of 3.97 inches of rainfall, edging out the previous record of 3.82 inches set in December 1991.

“Those two events far exceed all others since 1950,” Nielsen-Gammon explains.

“The third-highest five-day total is a mere 3.31 in June 1961.

“The combined total for both recent events was 5.32 inches for the 10-day period ending Oct. 31, 2015. This was also a record 10-day total, breaking the previous record of 4.68 inch set in April 1957.”

He says these totals come on the heels of several springtime rainfall records.

Last May, at 9.05 inches statewide, was the wettest single month on record going back to 1895, well above the previous record of 6.66 inches from June 2004, according to official data from the National Centers for Environmental Information.

Also, data shows that since 1950, the wet weather during May also holds the record for the wettest 30-day period, easily exceeding the 8.64 inches in the 30-day period ending Sept. 25, 1974.

“A contributing factor to both events is the strong El Niño presently in place in the tropical Pacific,” Nielsen-Gammon adds.

“A moderate-to-strong El Niño tends to draw the jet stream farther south across the United States, simultaneously enhancing the flow of moisture and increasing the instability. “

In addition, he says a series of upper-level troughs enhanced the upward motion. In both May and October, this happened at the same time that rich tropical moisture was flowing into Texas at low levels.

El Niño also caused elevated sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean, increasing the amount of moisture being picked up by the atmosphere and being carried aloft across northern Mexico and Texas, the Texas A&M professor explains. While moisture aloft doesn’t contribute much rainfall directly, it helps prevent rain in thunderstorms from evaporating before it reaches the ground, Nielsen-Gammon points out.

“Climate change was probably responsible for a little extra rainfall by enhancing the moisture content of the atmosphere, providing more water vapor that could then condense and fall as rain,” he notes.

“Scientists do not yet know to what extent climate change may have affected the overall weather patterns, or whether those changes in weather patterns caused an increase or decrease in Texas rainfall beyond what would have happened anyway.”

He adds that with El Niño still in place, additional wet weather this winter and spring is likely, though it would be difficult to top the individual rain events that have already occurred.

“Historically, above-normal rainfall is likely but is not guaranteed, and the two strongest El Niños in recent history were only associated with near-normal rainfall,” Nielsen-Gammon says.

“On the other hand, the December 1991 rainfall record that was just broken was set during the fourth-strongest El Niño of the past 120 years, so additional widespread heavy rainfall is certainly possible this winter.”

Media contact: Keith Randall, Texas A&M News & Information Services.