Texas Coast Dodges Seaweed This Summer

A year ago, Galveston and parts of the Texas coast were awash with sargassum, the technical name for seaweed, as the stinky stuff made its way to shore and ruined a day on the sand for thousands of beachgoers. So where is the seaweed this year? You can thank a slight direction in ocean currents, says a Texas A&M University at Galveston professor.

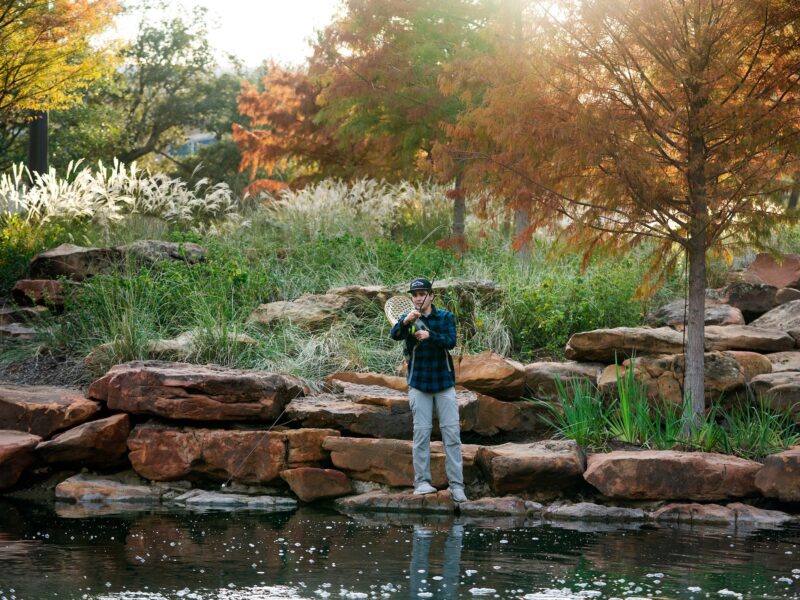

Tom Linton, assistant professor of marine resource management at the Galveston campus, says that Galveston and almost all of Texas has dodged the sargassum waves this year, although that hasn’t been the case for large chunks of the Caribbean, where sargassum has played havoc with tourism all summer.

“Normally the loop current that passes through the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico is seasonally static. But this year, the loop current has adjusted somewhat more in an easterly direction, and this adjustment has created a sort of filtration system into the Gulf, meaning the sargassum has not been headed our way,” Linton explains.

“As a result, we don’t have the huge mats of sargassum that much of the Texas coastline experienced in 2014.”

The seaweed is usually contained in the Sargasso Sea, a huge sort of floating ecosystem in the North Atlantic that stretches for almost two million square miles.

Last year, currents carried the sargassum directly toward the Galveston area, and beaches were literally swamped with the large mats, rising six feet high in some places. Beach officials said it was the worst outbreak in at least 50 years to hit the Galveston area.

Port Aransas, Corpus Christi, Padre Island and other Texas coastal locations also got many tons of the sargassum.

Another big negative of the seaweed: it stinks. The large mats serve as a personal condo for numerous types of marine life such as shrimp, plankton, small fish, crabs and many others, and eventually many of them die, creating a pungent odor for miles.

The good news is that the seaweed mats are a dandy refuge for youngturtles as they make their way seaward after hatching.

Texas A&M-Galveston researchers, with the help of NASA, developed a means of tracking large mats of sargassum earlier this year, creating an app called SEAS (Sargassum Early Advisory System). The SEAS system uses satellite technology to track the sargassum and project its movements as it drifts through the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

“It (SEAS) has done exactly what we thought it would do, and it has an accuracy rate of 98 percent,” Linton says.

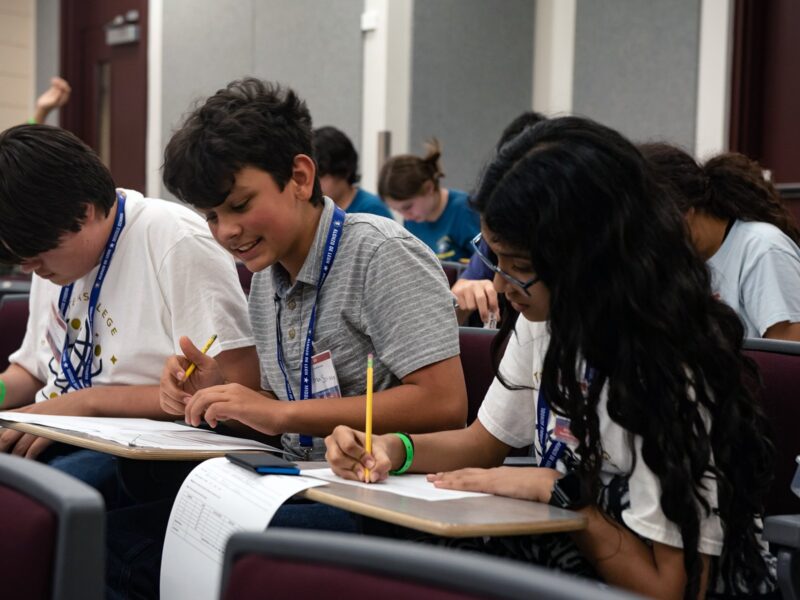

“It also serves as a great teaching tool in some of the predictive models used in marine management classes.”

The SEAS system was used recently on a minute-by-minute basis by many Caribbean beach destinations that thrive on tourists. St. Thomas, Tobago, and parts of the Yucatan Coast were hit hard by waves of sargassum in recent weeks, with Mexico announcing it would use 4,000 temporary workers and spend at least $9 million on sargassum cleanup efforts.

“Sargassum has no means of locomotion – it just floats along,” says researcher Robert Webster, who has studied the seaweed for years.

“Sargassum is always at the mercy of the wind and ocean currents. It goes where the currents take it.”

Webster and Linton have developed ways to compact the seaweed into bales, similar to hay, and combined with sand, it can be used to prevent beach erosion, which is a never-ending problem in Galveston.

They are also looking into ways where the sargassum might be edible for livestock.

The SEAS system is currently detecting large areas of sargassum north of the Yucatan Peninsula.

Media contact: tamunews@tamu.edu.