Researchers Find Potential New PTSD Treatment

A drug commonly prescribed to treat high blood pressure can also facilitate a form of learning used to reduce fear in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to researchers at Texas A&M University.

The study, “Noradrenergic blockade stabilizes prefrontal activity and enables fear extinction under stress,” published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is authored by Texas A&M Psychology Professor Stephen Maren, Assistant Research Scientist Paul Fitzgerald and Texas A&M Institute for Neuroscience graduate students Thomas Giustino and Jocelyn Seemann.

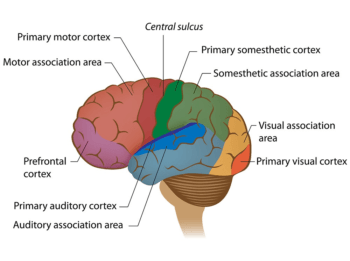

Maren, who specializes in the study of fear and anxiety, says the research was designed to examine whether dampening a neurotransmitter system that conveys stress signals to the cortex would facilitate prefrontal cortical function and enable the form of learning (called extinction) involved in suppressing fear memories.

“Patients with PTSD have trouble learning to suppress fearful memories of their traumas,” Maren explains. “We reasoned that the high levels of stress experienced by PTSD patients might inhibit brain areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, involved in learning to suppress fear.”

The researchers used the drug propranolol, a beta blocker used to treat high blood pressure, angina, irregular heartbeat and other heart conditions.

“We recorded the activity of single neurons in the prefrontal cortex in behaving rats to examine whether stress-induced changes in prefrontal cortical activity could be minimized with propranolol, which blocks stress signaling in the brain,” says Maren. “We also examined whether propranolol would eliminate stress-induced impairments in extinction learning.”

In the experiments, Maren explains, rats underwent fear conditioning in which a sound was paired with a mild electric foot shock; extinction training, in which the sound was presented many times alone (to signal it was safe), was conducted immediately after conditioning.

“Under these conditions, extinction learning is poor because of the recent stressful experience (having been shocked) — we call this the ‘immediate extinction deficit,’” Maren explains. “We wondered whether propranolol administration prior to extinction training under these stressful conditions would eliminate the deficit.”

As they hoped, Maren says propranolol administration dampened shock-induced changes in prefrontal cortical neuronal activity and facilitated extinction learning under stress (i.e., it eliminated the immediate extinction deficit).

PTSD is a psychiatric illness precipitated by a experiencing a real or perceived threat to one’s safety, or witnessing a similar threat to someone else’s safety. It is characterized by intrusive memories of the trauma, hyperarousal and stress, and avoidance of places or situations that retrieve memories of the traumatic event, among other things.

“The most common form of treatment is a cognitive-behavioral therapy called exposure therapy, which encourages PTSD patients to suppress their fear of stimuli, places, and events that remind them of their trauma,” Maren explains. “Extinction learning, in which reminders of the trauma are presented in a safe setting, is at the heart of exposure therapy. Exposure therapy is effective in many cases, but its effectiveness tends to wane with time and fear often returns – what is called ‘fear relapse.’”

Maren notes that although all of the work so far has been done in animals, “it has important implications for treating trauma and stress-related disorders in people.”

He says combining propranolol with traditional behavioral therapies such as exposure might be particularly helpful in promoting extinction learning and lasting fear reduction in PTSD patients and recently traumatized individuals.

“Neither intervention would be expected to be effective alone, particularly in patients experiencing high levels of stress,” he adds.

Media contact: tamunews@tamu.edu.