Estrogen-Eating Bacteria = Safer Water

Usually, when you mention bacteria in connection with water, it’s a bad thing. But one Texas A&M engineering researcher believes the right bacteria are a natural weapon for fighting an emerging water contaminant: estrogen.

Increasingly sensitive methods of screening water for polluting substances allow environmental scientists to monitor traces of previously undetected contaminants in otherwise clean water: trace amounts of pharmaceutical and personal care products ranging from antibiotics to anesthetics and, especially, estrogens.

The presence of any of these drugs concerns public health officials, but Dr. Kung-Hui (Bella) Chu, an associate professor in the Environmental and Water Resources Engineering Division of the Zachry Department of Civil Engineering, is particularly interested in estrogen in water.

“We are talking about trace amounts of these materials,” Chu said. “We’re talking about concentrations of, usually, nanograms per liter. It’s very low.”

But even at these low concentrations, Chu said, the presence of estrogens in water is something to be concerned about.

So far, the most direct evidence of the impact of estrogens in water has been found in male fish swimming downstream from estrogen-containing water sources. Some have been found to have both male and female sexual characteristics, such as partially developed ova, or eggs, in their testes. Fish damaged in this way have been found in the United States, Great Britain, Italy and other places.

This sex-related damage to fish may not be significant in itself, but researchers suggest that it’s a warning of potential dangers to humans. Estrogens in drinking water could affect male fertility by interfering with sperm production. Links between environmental estrogenic compounds and several kinds of cancer, especially breast and testicular cancer, also have been suggested.

Estrogen and estrogen-like compounds find their way into water from many sources. Naturally occurring estrogen compounds come from livestock urine and feces, and from human excretions and contraceptives and hormone replacement medications. Other estrogen-like compounds can be found in everything from insecticides to plastics, and they all find their way into the water supply.

About 80 percent of 139 U.S. rivers are contaminated with these trace compounds.

Existing water treatment processes — which often involve naturally occurring bacteria in sewage sludge — remove as much as 94 percent of estrogen from untreated water, but what remains is still potent enough to cause damage to fish, and, researchers fear, humans. Although harmful estrogens often remain in water after treatment, this performance is not surprising, Chu said, because conventional water treatment processes weren’t designed to deal with estrogens.

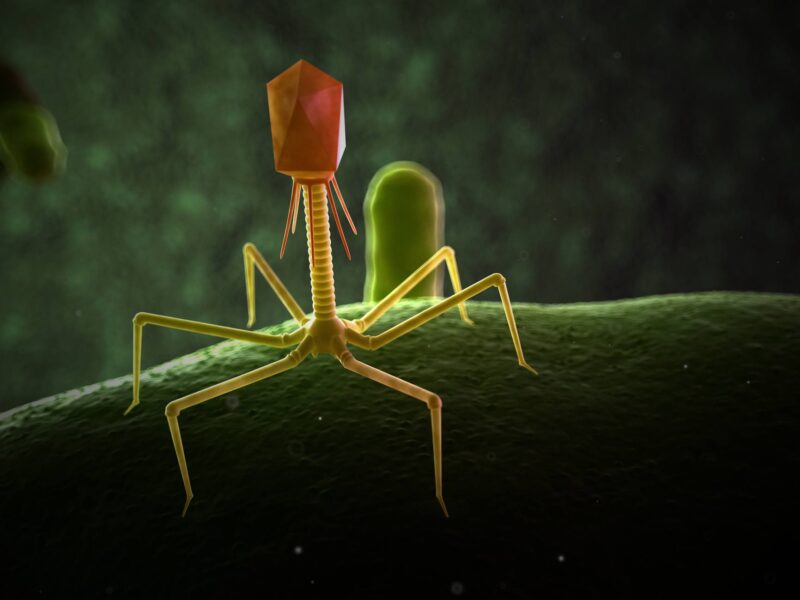

Bacteria to the rescue

Chu said she has long been interested in biological approaches to water-quality problems. In wastewater treatment, this means using bacteria to clean up the wastewater. She and her colleagues are looking for bacteria that will make existing treatment processes more effective. The main function of these bacteria is to break down organic pollutants in water. Her main focus is on searching for wastewater bacteria that are capable of breaking down estrogens into harmless end products.

If she finds them, the estrogen degradation ability of these bacteria could be capitalized in engineered bioreactors to remove estrogens.

Chu and her colleagues have found 14 different species of bacteria that can break down estrogens, and they’ve published details of their findings in scientific journals. All 14 break down 17ß-estradiol, a female reproductive hormone also commonly used in oral contraceptives, to a less-potent compound called estrone. Three of the 14 break down estrone further into harmless end products, and one (strain KC8, a Sphignomonasstrain) does it particularly quickly.

The researchers now are trying to understand the enzymes and degradation pathway that a single bacterium uses to destroy estrone. Their idea is to define the optimal growth conditions to promote the growth of these estrogen-degrading bacteria in biological wastewater treatment processes as a means to break down estrogens quickly and completely — and relatively inexpensively.

The researchers have focused considerable attention on characterizing the Sphignomonas strain KC8, which is known for its ability to utilize 17β-estradiol, estron, and/or testosterone as its sole carbon and energy source. In a 2011 paper in the Journal of Bacteriology, Chu and a research team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences presented the first known genome report of this estrogen-degrading bacterium. Knowing more about the strain KC8 will help researchers understand how KC8 can degrade 17β-estradiol into non-estrogenic end products.

Chu’s research team has detected trace levels of strain KC8 in municipal wastewater treatment plants and examined the feasibility of adding the strain KC8 for enhanced estrogen removal in synthetic wastewater. Chu’s group believes the strain KC8 may play an important role in estrogen removal.

“Adding such a bacterium could be an efficient and relatively inexpensive way to proactively avoid adverse health effects from estrogens,” Chu said.

Media contact: tamunews@tamu.edu.